We love Sardar Fauja Singh. Â We really, really do.

On Sunday, Fauja Singh will run his final race in Hong Kong at the tender age of 101.  Jezebel recently covered Fauja Singh in a piece about  women’s rights, and just today Jordan Conn wrote a compendious and inspiring article for Outside The Lines on ESPN about Fauja Singh’s life and the “missing” Guinness Book of World Records title.  This article, along with stunning photographs, spread like wildfire on Facebook and Twitter today – reminding us just how much the world loves Fauja Singh and what he represents.

On the first day of training, Fauja arrived limber and energetic and dressed, as he believed was perfectly appropriate, in a dazzling three-piece suit. Harmander told him he needed a wardrobe change. After adamant protests, Fauja relented, ditched the suit and bought running gear. He showed up every day after that, building his routine around his training schedule. His mileage increased as the weeks passed. Race day arrived. After 6 hours and 54 minutes, 4:48 behind winner Antonio Pinto, Fauja crossed the finish line. At age 89, he was a marathoner. Soon, he would be a star.

We will be wishing you well on Sunday, Fauja Ji! Â Thank you for continuing to be such an activist and a positive soul and for reminding us of the importance of health and happiness.

– The Langar Hall

“The bodies of Shindiver Grover, 52, his wife Damanjit, 47, and their two sons, Sartag, 12 and Gurtej, 5, were found in their first-floor apartment in Johns Creek, Ga., at around 11:30 a.m. Monday, according to local reports.”

(Source: NY Daily News. Photo credit: CBS Atlanta)

Tragic news broke today that a Sikh family in Atlanta, Georgia, was found dead in their home. The bodies of father Shindiver Grover (52), mother Damanjit Grover (47) and their two sons, Sartaj (12), and Gurtej (5), were discovered in their apartment when Damanjit did not report for work on Monday.

Police are still investigating what is called a “complicated” crime scene, but believe it was a murder-suicide:

The nature of the murder – the city’s first since it was incorporated in 2006 – was troubling to even the most senior investigators, [Johns Creek police Chief Ed Densmore] said.

“We are all human. We’re all parents. We have families,” Densmore said, according to local CBS News.

“You deal with something like this, it will take a little bit out of you, of course.”

Few details have been released at this point. Prayers for the departed souls and condolences are offered to those who knew the family.

While we are still learning about the tragedy, Sikhs in the United States who are seeking resources to deal with domestic issues can contact the Sikh Family Center, who provides a confidential “culturally specific peer-counseling and non-emergency support for community members in Punjabi and English.” The Sikh Family Center message line can be reached at (408) 800-SEVA or (408) 800-7382.

For more immediate needs, the National Domestic Violence Hotline is available in 170 languages at 1−800−799−SAFE (7233). In case of emergency, always first call 911.

[Cross-posted on American Turban]

Most of us are probably familiar with the history of the first wave of Punjabi migration to California in the late 1800s and early 1900s.  These pioneers, many Sikhs, set up the country’s first gurdwara in Stockton, formed the Ghadhar Party to overthrow the British Raj, and many ended up marrying Mexican women. I learned about this fascinating history way later than I should have, but have noticed more and more consciousness of these early migrants and their descendants over the last several years.

These pioneers, many Sikhs, set up the country’s first gurdwara in Stockton, formed the Ghadhar Party to overthrow the British Raj, and many ended up marrying Mexican women. I learned about this fascinating history way later than I should have, but have noticed more and more consciousness of these early migrants and their descendants over the last several years.

A book that just came out unearths a lessor known history of early South Asian migration to the United States. A few decades after this Punjabi migration to California came a smaller, but no less interesting wave of South Asian immigration (Bengalis) to the east coast.  This little-known history is documented in a new book by Vivek Bald called Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. Like their Punjabi predecessors in California, these mostly Muslim migrants were working class, dealt with a great deal of racism, and married women from other communities of color and immigrant communities.

Bald, also a filmmaker (who made an amazing film about the British Asian underground music movement of the 1990s called Mutiny: Asians Storm British Music), is also working on a documentary version of the book entitled In Search of Bengali Harlem, which you can preview here.

I haven’t yet read the book but am really looking forward to checking it out. As you’ll see from the blurb below, these stories have much in common with those of the early Punjabi migrants, even if they were working in different industries and came from different parts of South Asia.

Guest blogged by Santbir Singh

I try to imagine the government coming to my house one morning and taking my five year old daughter and eight year old son away to a boarding school hundreds of kilometres away. I try to imagine that at this school, my children’s hair will be cut, their dastars and kakkars will be removed and they will be forcibly baptized as Christians. I try to imagine that they will be beaten for speaking Panjabi, reading Bani or trying to maintain their religious and cultural traditions. I try to imagine that even their basic health needs will not be looked after and they may well die from treatable infections and diseases. And then, I must admit, I am not able to imagine the rest; I can not bear to imagine them being abused, assaulted, beaten and raped.

That is what occurred in this country for one hundred years as the Canadian government, along with government sanctioned church groups, kidnapped First Nations children from their homes and took them to residential schools where unspeakable horrors were committed on them. Of course the history of colonization in the Americas does not begin with the Residential School system but is in fact a legacy going back centuries. It is estimated that 90 to 95% of all indigenous people living in the Americas were killed by smallpox within the first century after European first contact in the late 1400’s. It is difficult to fathom death at that scale. Those that remained had their land stolen and were forced onto reservations to live as non-citizens in their own lands.

As a nation, Sikhs are extremely proud of our own anti-colonial struggle against the British. Yet we have completely failed to acknowledge that in Canada we have succeeded due to the colonial oppression of other nations. This land where we build our homes and businesses was the land of nations that lived here for tens of thousands of years. Yes, one hundred and seventy years ago the British annexed Panjab and ended Khalsa Raj. But the British did not exile us from our own villages and towns. The British did not take our land and build new cities. The British did not migrate to Panjab and force us to live on inadequate reserves.

Guest blogged by Simran Jeet Singh

Last week, people around the world watched a Sikh with a turban and beard – Gurpreet Singh Sarin – charm the judges on the iconic television show, American Idol. The show’s judges and producers played up his nickname, the Turbanator, and almost immediately, #Turbanator began trending nationwide on Twitter. As is often the case, however, the ugly face of bigotry reared its ugly head and reminded us all of the problems faced by Sikhs around the country. Countless Americans equated the contestant’s turban and beard with terrorism, and #Osama also began trending across the country.

Last week, people around the world watched a Sikh with a turban and beard – Gurpreet Singh Sarin – charm the judges on the iconic television show, American Idol. The show’s judges and producers played up his nickname, the Turbanator, and almost immediately, #Turbanator began trending nationwide on Twitter. As is often the case, however, the ugly face of bigotry reared its ugly head and reminded us all of the problems faced by Sikhs around the country. Countless Americans equated the contestant’s turban and beard with terrorism, and #Osama also began trending across the country.

Gurpreet has little control over how the producers of American Idol choose to project his image. Yet he has done an incredible job of working within the system to create positive change, and his breakthrough performance is something from which we will all benefit for years to come. More importantly, we as a community cannot learn how to build our image in greater America if we do not see Sikhs experiment within mainstream media and learn from those experiences. Certainly there were moments on the show that could have been improved, and while it is important to recognize and build upon these for the future, it is also important for us to take this moment to enjoy this unprecedented moment in our community’s history.

Guest blogged by Gunita Kaur Singh

Being a nonconformist builds character, but only when it is exercised within a certain framework of values. A prime example of this lifestyle is embodied within the Sikh religion.

Gunita’s father

Sikhism is very progressive for it allows the practitioner freedom from dogmatism, hence distinguishing it from other religions. However, it is encouraged to use said freedom for the purpose of enhancing a Sikh’s devotion to God and truthful living.

Guru Nanak was a definite nonconformist during his time because he spoke out against the subjugation of women to men, the anthropocentric concept of God, and the prominence of ritualism. The release from these binding ideals gives a Sikh the freedom to live her life as she wishes; even in simply viewing God as the universe itself, a Sikh must still appreciate and value God, but she has the ability to do so in the manner which is most personal and ideal for her mindset. This is the best example to depict nonconformity within a values framework.

Alan Keightley had said, “Once in a while it really hits people that they don’t have to experience the world in the way they have been told to.”

Nanak realized this because a central idea which he would teach seekers of his knowledge was that we belong to nobody, and nobody belongs to us. This notion helps to emancipate individuals from the confinement of bodies, and transcend into spirit form. It also tells us that we never have to be marginalized to institutions or authoritarians.

(Disclaimer: I’ve never watched American Idol before. It’s true.)

Most of you are probably already well aware that a young Sikh named Gurpreet Singh Sarin appeared on American Idol last night and made it through the first hurdle. In case you missed it, here is the clip from his audition in front of the judges.

Like most of you, I’ve been barraged with posts on Facebook and Twitter about Gurpreet’s success on the show last night, mostly expressing excitement and support for the self-proclaimed “Turbanator.” The vibe I’m getting from all the posts I’m seeing from Sikhs is that this big moment for Gurpreet is a big moment for the Sikh community in the US, perhaps an opportunity for some positive representation in popular culture. The Sikh Coalition and SALDEF have tweeted congratulations to Gurpreet as well, and the overall sentiment appears celebratory.

I share some of this excitement, or at least fascination, but the whole thing is also making me cringe a bit. I don’t want to unnecessarily rain on this parade because I do think it is an interesting moment and opportunity. I also think Gurpreet is a solid singer and did a great job at handling what must have been an uncomfortable situation on many levels.

A goat

A sacrificial lamb

Halal meat

Her blood runs dry at the bottom of a river

Cleansing the land

Peshawar

Punjab

Pakistan

India

Afghanistan

Sri Lanka

The tip of my soul

New Delhi

Amritsar

Anandpur Sahib

Chandigarh

Jalandhar

Ludhiana

My constellation of stars

Drip drip dripping

Blood seeps into earth

One quick slice from the neck

Less painful that way

More fertile that way

Mothers, sisters, daughters

We bury red splashes

Virgin ground

In a recent piece on BBC Radio 4, titled Beyond Belief – Women in Sikhism, host Ernie Rea starts off with this statement,

“The Sikh religion is the world’s fifth largest… the men are often easily recognized – they wear turbans and leave their hair uncut. Â The fundamental message appears to be simple – God is one and all people are equal. Â But are some more equal than others? Â If the Sikh scriptures are consistent with a feminist agenda, why do some Sikh women feel like they are second class citizens?”

The host is joined by a panel of three women to discuss the issue of equality within the Sikh faith – Navtej Purewal, Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences at Manchester University; Eleanor Nesbitt, Professor Emeritus at the Institute of Education in the University of Warwick; and Nicky Guninder Kaur Singh, Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Colby College.  The panelists did a great job of explaining what in fact Sikh scriptures say about equality and the role of women.  In addition, they helped identify the gaps that still exist between what is written and how it is practiced.  While these women speak predominately from an academic standpoint and not necessarily the community Sikh women’s voice, i think they brought forth a much important discussion for our community as a whole.  It was also quite eye-opening to hear the non-Sikh perception of our faith, represented by the host.

While parts of the conversation – often guided by host Ernie Rea – landed on discussions around topics that are common to this blog, (i.e. if Sikhi believes in equality, why does Panjab have the highest rates of female foeticide and if Sikhi is an egalitarian faith, why do men and women sit separately within the Gurdwara), the overall discussion was helpful as it raised questions that need to be addressed if changes are going to be made. Â The host began by asking whether or not the Sikh scripture does include a feminist agenda.

Purewal noted that the the Guru Granth Sahib was very revolutionary and, as far as doctrine, it does have the potential to be feminist.  However, due to social convention the message has not been actualized among Sikh communities, whether in India or within the diaspora.  Nesbitt suggested that since the scripture is predominately written in poetry, it is thus open to interpretation and that this is potentially the cause for much of the tensions felt by contemporary women.  Singh goes on to say that even the word “God” brings forth the notion of a male entity which is a starting point for many misconceptions and in fact, in the Guru Granth Sahib Ik Onkaar does speak to being gender-free.

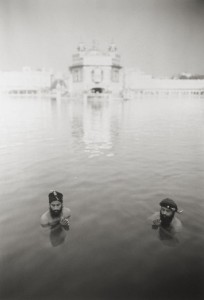

Today’s Lens section of the NYTimes highlights the work of photographer Kenro Izu, whose images of sacred spaces in India will be on display at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in Manhattan.  The article opens with a black and white image of a woman sitting on the parkama facing the Darbar Sahib in Amritsar and is followed by other striking images showing how faith plays out in daily life.

The exhibition, titled “Where Prayer Echoes” focuses not on the structures of these sacred spaces, but rather on the individuals who go to pray at these sites.  This particular exhibition covers the photographer’s trip to India and includes portraits of people who follow various religions, from Hinduism and Islam to Sikhism and Jainism.

For more than 30 years Mr. Izu has been on a pilgrimage of sorts, taking exquisitely classic landscapes and portraits of sacred places and the faithful.

At first, he was interested only in pictures of grand temples, pyramids and holy sites.

But then he had a revelation.

“Before, I was just attracted to form,†Mr. Izu said. “In the last 10 years, I am more interested in the humans who go into these structures. That is where the spirit is. Without the people who pray or offer flowers, it’s just a structure.â€

The exhibition will be on display through February 23rd 2013.

A young Singh in the UK has been in the spotlight the last few days after his appearance on a dating television show called “Take Me Out.” I just heard about it a show on BBC Radio 1 hosted by Nihal, which you can listen to in its entirety here. Nihal speaks with Param, the dating show contestant, and takes comments from listeners, who discuss Param’s appearance on the show and more generally whether turban-wearing Sikh men are discriminated against when it comes to dating and marriage. As you’ll see in the clip below, as soon as Param comes out, 20 of the 30 women turn their lights off, indicating no interest in him. One woman who left her light on said she is interested in him because she could use Param’s turban to store her phone.

I recommend checking out Nihal’s discussion on the BBC especially starting at around 44:00 into the show if you don’t have time to listen to the whole thing. One caller named Jasminder asserts that when Param came down, it became more like a comedy show and less like a dating show given how the women and audience reacted. He continues that turban-wearing men often feel invisible to women, not literally, but “when it comes to actually going out with someone.”

Guest blogged by a Kaur

A note from the author: Thank you Gurlene Kaur for starting the conversation.

ਚà©à¨ªà©ˆ ਚà©à¨ª ਨ ਹੋਵਈ ਜੇ ਲਾਇ ਰਹਾ ਲਿਵ ਤਾਰ ॥

By remaining silent, inner silence is not obtained, even by remaining lovingly absorbed deep within.

1

19 years later

I still hear his cry tugging at my heart

In the middle of the night

Glistening red blood fills my consciousness

I sit up, breathless

My apartment

New York City

I see something familiar

Then drift back to sleep.

2

Sleep still in my eyes

I pull on a purple pajami and wrap myself in a chunni

One by one we pile into the car

Kirtan playing in the background

My 4 year old cousin sits next to me expectantly

Long black curls sneak out from underneath her pink hat

Betraying her age, revealing her true spirit

A kid-sized computer and backpack grace my lap

I follow the lilt of her voice as we pass by field after field.

Co-blogged with Nina Chanpreet Kaur

(source: Daily Record and Sunday Mail)

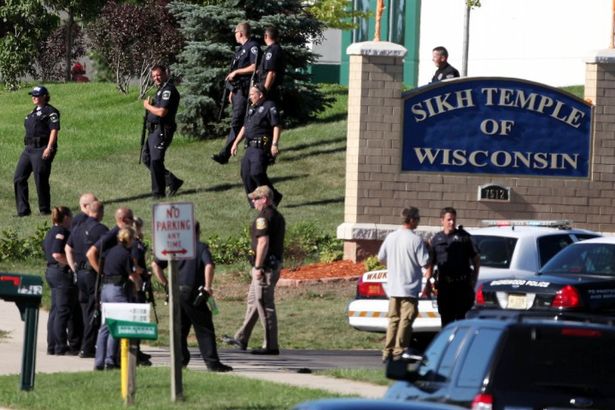

“All the talking is done and now it’s time to walk the walk / Revolution’s in the air 9mm in my hand / You can run but you can’t hide from this master plan.” (Song lyrics by Wade Michael Page’s band End Apathy)

A few weeks ago, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) closed its investigation into the mass shooting that occurred at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in August, in which six Sikhs were murdered and wounded four others, including Lieutenant Brian Murphy of the Oak Creek Police Department, and Punjab Singh, who is still in a long-term care facility receiving treatment.

The FBI’s conclusion does not bring any closure. In the wake of Oak Creek, the specter of a growing white supremacist movement has not been adequately addressed by the media, policy makers, nor law enforcement agencies. This frames the issue of hate crimes against Sikhs as something almost incidentally perpetrated by independent murderers, and the stalling by the FBI to accurately and consistently report anti-Sikh and other hate crimes as well as link it to domestic terrorism reinforces the sense that the white supremacy movement is something federal, state and local government are not taking seriously or prioritizing. Historically, the white supremacist movement at-large has perpetrated heinous crimes fueled by hate and bias often in the guise of a member gone rogue as we saw in Oak Creek in August 2012.

Disclaimer for non-Sikhs: In writing this, I am not in any way saying Sikhs are somehow more predisposed to violence than any other community. The last thing I want to do is perpetuate racist stereotypes about Sikhs. However, I write because I see an opportunity for introspection in our community. If you choose to continue reading, I encourage you to think about how similar dynamics may play out in your community/ies.

I am still having a hard time wrapping my head around what happened in Newtown, CT last week, especially given the kind of year it has been here in the United States, from Aurora, CO to Oak Creek, WI.

For now, I want to pick up the conversation where Nina left off. Indeed, heartbreak is the right word for how I’m feeling about the deaths of children and adults due to gun violence, including those that don’t make the national news headlines, whether they are youth of color shot by police officers or families in Afghanistan bombed by the U.S. military.

Today, the depth and pervasiveness of violence in American culture is more clear than ever. The evening of the tragedy in Newtown, Michael Moore who made the Oscar-winning film about school shootings in 2002, Bowling for Columbine, stated:

I like to say that I sort of agree with the NRA when they say, ‘Guns don’t kill people, people kill people,’ except I would just modify that a bit and say, ‘Guns don’t kill people, Americans kill people,’ because that’s what we do. We invade countries. We send drones in to kill civilians. We’ve got five wars going on right now where our soldiers are killing people–I mean, five that we know of. We are on the short list of illustrious countries who have the death penalty. We believe it’s OK to kill you when you’ve committed a crime.

Guest Blogged by Nina Chanpreet Kaur

The year 2012 has been a series of heartbreaks. There is perhaps no greater pain than surviving a child. From Oak Creek, WI to the children whose lives were innocently lost in Newtown, CT and the millions of others who die as victims of violence every day, my heart breaks. So far, our response as a nation in the wake of Friday’s tragedy has been messy and presumptuous, but also clear and action-oriented at times. Deep pain, anguish, grief and conflict tend to have that affect: forcing us into action beyond our own daily lives and bringing us a greater sense of clarity.

In the wake of Sandy Hook, conversations about mental health, gun control laws and the root of violence in our schools, homes and communities continue to flash before our eyes. In response, we each do what we know best — for some it is grappling with a new world view to make space for such loss, for others it is taking time to grieve and release anxiety, and for several more it is taking quick action. So far, the Sandy Hook tragedy has transformed the views of some politicians and community members alike — Sikh Americans included. I am hopeful that this will bring increased attention and action to the problem of gun violence that also deeply affects the Sikh community.

The Sikh American community has responded to Sandy Hook by attending and organizing vigils across the country. A young Sikh boy imparted a beautiful message to the deceased children and national community, sharing his condolences. The Kalekas, who lost their father and members of their sangat to the tragedy in Oak Creek, have organized a movement around the film Nursery Crimes and met on Monday on the steps of City Hall in New York City along with Mayor Bloomberg and other politicians demanding gun control. They plan to travel with survivors from Oak Creek, Aurora and Columbine to Newtown, CT to lend a helping hand. Both Amardeep and Pardeep Kaleka have been instrumental in shining light on the roots of violence and hate and taking quick action. Producing several videos, erecting Serve 2 Unite and building a movement around Nursery Crimes are among a few of their many tremendous efforts. We need more Sikhs who are willing to speak up about the issue of gun control and systemic violence.

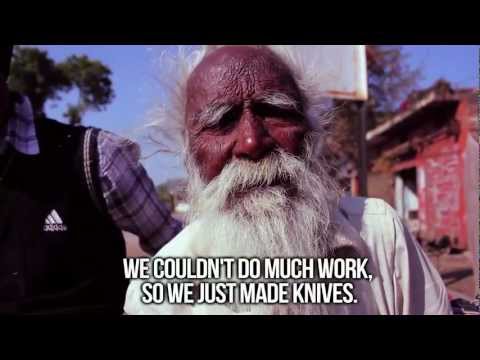

As a community, we have an incredibly rich history and yet we often know so little about it. The first time I learned about the Sikligar community was after watching Mandeep Sethi’s documentary at a local film festival, about this community of Sikhs known to be the weapon makers of the Khalsa army. Unfortunately, very little is known about the Sikligars by those living both within and outside of India and Mandeep’s film will be a first glimpse into the community for many. The Sikligars are found across India – displaced through years of colonization and government oppression. It is known that the community was given the name Sikligar by the 10th Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobind Singh Ji and yet even this honor has not prevented the community from struggling – Sikligars now live in extreme poverty in the slums of Rajasthan, Delhi and Agra. There are also encampments in Punjab. Although this community has been largely illiterate for the last 300 years (focusing on their trade and thus livelihood), the Sikligars are beginning to empower themselves through different means such as education. For the first time, the full length documentary is available online! Over the past few months, I’ve joined Mandeep at several film screenings of his documentary and I’ve asked him some questions about SIKLIGAR which you can find after the jump.

Guest blogged by Nina Chanpreet Kaur

August 5th, 2012. 1:33pm. A text message from my best friend: “hostage situation at sikh temple in wisconsin. on al jazeera right now.” We pulled over and exchanged glances, holding our breath it wasn’t an attack perpetrated by someone within the Sikh community. Earlier that morning we rowed in unison, kayaking down the Hudson. Her voice coaching my every movement. Later, riding side by side, we biked to the tennis courts. The wind blowing in our faces and trailing behind our backs, sheer joy and pleasure breezed through me. We had been riding our bikes home when we pulled over. After we said our goodbyes and went our separate ways, I went to hit some tennis balls. The news hadn’t yet sunk in. Once home, my entire being collapsed. I couldn’t avoid the flood of emails, messages and calls. I kept replaying the last few hours. The extreme contrast of the deep pleasure of my morning and the tragedy of Oak Creek felt like some sort of betrayal.

As the shock lifted and the news sunk in, I laid my forehead against the naked floor of my Manhattan apartment and wept. I wept for children, little bare feet hitting cement pavement running for safety. I wept for women crammed into a closet, gunshots threatening to penetrate their bodies. I wept for the pain of separation. I wanted to be there, I wanted to hold each of the bleeding victims in my arms. I wanted to sit next to Wade Michael Page. Make him stop. Have a conversation, maybe a cup of tea. I wept for the memories of the safe gurdwara that cradled me with kirtan as a child. Such a place no longer existed.

News from Wisconsin consumed me. Guilt. Grief. Why wasn’t I there? How does the universe exist in such extremes? At sunset, I picked myself up and started to write. I wrote emails. Long emails. I asked for a vigil. I planned a vigil. I wrote poems. I published them. I lost my appetite and any desire to eat, sleep or cook. I stayed awake through the night to organize. There was no such thing as comfort or rest for me in the weeks following Oak Creek. Heartbroken, the sadness cut through my very center. Organizing was my only way out.

Last week, two separate brutal attacks against Muslim men took place in Queens, New York. On November 24th, 72-year-old Ali Akmal was nearly beaten to death while going on his early morning walk and remains in critical, but stable, condition.

CBS New York reports:

Akmal’s tongue was so badly swollen that he couldn’t talk for two days. When he finally could, he told police that when he first encountered the two men, they asked him, “are you Muslim or Hindu?”

He responded “I’m Muslim,” and that’s when they attacked.

The beating was so savage and personal, Akmal was even bitten on the nose.

Just a few days earlier, 57-year-old Bashir Ahmad was beaten and stabbed repeatedly as he entered a mosque in Flushing, Queens early in the morning on November 19th. The attacker yelled anti-Muslim slurs at him, threatened to kill him, and also bit him on the nose. Ahmad was hospitalized and received staples in his head and stitches in his leg.

These vicious attacks come just a few months after the white supremacist rampage that left six Sikhs dead in Oak Creek, Wisconsin in August, followed by a string of at least 10 separate anti-Muslim attacks around the country in the two weeks that followed. And just over a year after the elderly Sikh men Gurmej Atwal and Surinder Singh were shot and killed on their evening walk in Elk Grove, California.

Needless to say, I was horrified last week when I heard about the attack on Ahmad and am even more horrified today after learning about Akmal,  a grandfather, nearly being killed in this act of violent hatred a few days later. The trauma of the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh for us Sikhs in, and there is little doubt that these recent attacks on Muslim men in Queens are rooted in the same type of bigotry that has so often made Sikhs targets since 9/11. As I’ve said before, our struggles are deeply connected.

a grandfather, nearly being killed in this act of violent hatred a few days later. The trauma of the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh for us Sikhs in, and there is little doubt that these recent attacks on Muslim men in Queens are rooted in the same type of bigotry that has so often made Sikhs targets since 9/11. As I’ve said before, our struggles are deeply connected.

The way I heard about the attack on Ahmad last week, though, was almost as troubling as the attack itself. I read this headline on NBC New York’s website: “Queens Mosque Stabbing Victim Says He’d Retaliate if Given Chance.”

At least 21 Palestinians in Gaza have been killed and hundreds more injured in the last week by the Israeli “Defense” Forces. Three Israelis have  also been killed in this latest escalation of violence in the region. The situation is dire, as Israel is now ramping up for a full on ground invasion of Gaza, an area of only 141 square miles inhabited by 1.7 million residents. One of the most densely populated areas in the world, it has also been called the largest open air prison in the world. (Read Ten things you need to know about Gaza for more).

also been killed in this latest escalation of violence in the region. The situation is dire, as Israel is now ramping up for a full on ground invasion of Gaza, an area of only 141 square miles inhabited by 1.7 million residents. One of the most densely populated areas in the world, it has also been called the largest open air prison in the world. (Read Ten things you need to know about Gaza for more).

Let us be clear: Israel is not defending its citizens. It is on an aggressive, offensive, politically-charged rampage. We must read beyond the deceiving mainstream media coverage to get the to reality of the situation (see this timeline of recent events). This isn’t about Hamas rockets or any dangers to the existence of the state of Israel. Phyllis Bennis wrote in the Nation:

So why the escalation? Israeli military and political leaders have long made clear that regular military attacks to “cleanse” Palestinian territories (the term was used by Israeli soldiers to describe their role in the 2008-09 Israeli assault on Gaza) is part of their long-term strategic plan. Earlier this year, on the third anniversary of the Gaza assault, Israeli army Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Benny Gantz told Army Radio that Israel will need to attack Gaza again soon, to restore what he called its power of “deterrence.” He said the assault must be “swift and painful,” concluding, “we will act when the conditions are right.” Perhaps this was his chosen moment…

This is primarily about Netanyanu shoring up the right wing of his base. And once again it is Palestinians, this time Gazans, who will pay the price. The question that remains is whether the US-assured impunity that Israel’s leadership has so long counted on will continue, or whether there will be enough pressure on the Obama administration and Congress so that this time, the United States will finally be forced to allow the international community to hold Israel accountable for this latest round of violations of international law.

If you pay taxes in the United States, you are helping fund Israel’s invasion. Just a few months ago, President Obama announced the addition of $70 million in military aid to Israel. We Americans are literally funding the atrocities being committed against our brothers and sisters in Gaza right now.

Guest blogged by Nina Chanpreet Kaur

In September, I attended a Sikh awareness training at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. Sitting in the audience, I watched and listened as the presenter referred to Sikh women in passing and brought the Sikh male experience and turban to the center of the stage. During the Q&A, a woman behind me stood up. It was evident that she had heard Kaur for the first time during the presentation. She pronounced it “hora” then “whore” until she was finally corrected to “Kaur” as in core. It reminded me of how obsolete Kaur has become. I was also reminded of a dear friend of mine who recently told me about a reunion visit she had with some of our long time, mutual friends. As the usual gossip and updates ensued, someone mentioned my change of last name to Kaur and whispers and glances shot around the room. One woman surmised that I had gotten married. I had at that point received many Facebook messages congratulating me on my marriage. When my friend assured them, despite their insistence, that I had not gotten married another woman speculated that I had just become suddenly religious and so of course I changed my last name.

Across the globe today, our last names generally link us to patriarchy through kinship reference and in many cases ethnic, national, religious and class ties as well. In India and the South Asian diaspora, someone’s last name alone indicates what village or city she is from, her religious affiliation, familial ties, and even her family’s occupation and class status. In 1699 Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the 10th Guru of Sikhism and my spiritual father, asked Sikh men to take on the last name Singh meaning lion and Sikh women to take on the last name Kaur meaning prince. This request was intended to bring equality to a society then entrenched in inequality through caste, classism and sexism. Our world today remains entrenched in inequality.

Guru Gobind Singh Ji’s call for Singh and Kaur was more than a request to fight classism and kinship preference, it was a demand to subvert the structure of patriarchy and class structure as we know it. It was a call for revolution, the type of revolution that happens every day when we make choices that force us to stand out and stand up for our values. The type of revolution that happens each time large numbers of people choose to do something different and effect change through subversion. You can imagine, then, my surprise and amusement at the irony of being congratulated on my marriage when I changed my last name from Singh to Kaur.