Guest post by Sarina Kaur

Guest post by Sarina Kaur

“A Sikh’s entire life is life of benevolent exertion”. Sikh Rehat Maryada (Code of Conduct)

Benevolent exertion. These powerful words along with countless examples from history, gurbani, and rehat remind us that to question, challenge, and think for the purpose of informing our actions according to the Guru’s teachings is a Sikh’s birthright, privilege, and responsibility. This benevolent exertion toward an egalitarian world and empowered society devoid of oppression is a standard rooted in our collective psyche. But to know this, is not enough. The first Sikh Feminist Conference in North America, by SAFAR: the Sikh Feminist Research Institute, seeks to unpack what this means for Sikhs of the 21st century.

Personally, at every turn in my own journey toward creating a life imbibed with thoughtful action toward a more just and humane world, I have craved to understand and experience the unspoken viewpoints of the Kaur experience. Today, few can deny that no matter where you look- within the Sikh social context or in the global context-the dominant narrative is not inclusive of the female voice; that our calibrated center-where we collide as a society-is not in line with the standards our Guru’s introduced. A space for expansive revival, attention, voice and praxis to the feminist values and egalitarian politics inherent within Sikhi is a step toward a more calibrated center.[1] SAFAR’s Conference Program promises such progressive steps.

Distinguished keynote panelists, Dr. Nikky-Gurinder Kaur Singh, Dr. Inderpal Grewal, and Palbinder K. Shergill will launch the discussions and introspections for the day while exploring the topic “What Do We Know?” By exploring what knowledge exists from various sources, this panel promises to dive into an exploration of the intersectionality of Sikhi, feminism and discourse on Sikh Feminism. Each of the panelists is a pioneer in her own right; while Dr. Singh is often fondly thought of as the mother of ‘Sikh feminism’, Dr. Grewal from Yale is lauded for her seminal work on ‘transnational feminism,’ while Ms. Shergill is a trailblazer in the courtrooms in Canada, and just recently distinguished herself as the only female lawyer in the Supreme Court, that too while articulating the fundamentals of religious freedom in a case about the religious freedoms for a non-Sikh-Sikhi in action! I look forward to their discourse and interaction with each other as moderated by writer and activist, Inni Kaur.

Guest blogged by Bandana Kaur

“Pavan guru paanee pitaa

Maataa dharat mahat

Divas raat du-i daa-ee daayaa

Khaylai sagal jagat”

-Guru Nanak SahibÂ

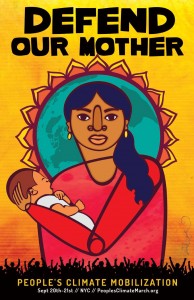

In honor of the Sikh concern for preserving ‘Mata Dharat’ (Mother Earth), Sikhs from cities across the northeast are joining the People’s Climate March in New York City on September 21st, the largest mass movement for climate justice in history.

Next week, world leaders are coming to New York City for a UN summit on the climate crisis. The world is urging governments to support an ambitious global agreement to dramatically reduce global warming pollution.

With our future on the line and the whole world watching, we’ll take a stand to bend the course of history. We’ll take to the streets to demand the world we know is within our reach: a world with an economy that works for people and the planet; a world safe from the ravages of climate change; a world with good jobs, clean air and water, and healthy communities.

Why Are We Marching?

We march because Sikhi affirms the sanctity of the Earth.

We march because the ecological basis of Sikhi rests in the understanding that the Creator (‘Qadir’) and the Creation (‘Qudrat’) are One. The Divine permeates all life, and is inherent in the manifest creation around us, from the wind that blows across land and skies, to the water that flows through rivers and seas, to the forests and fields and all creatures of land and sea that depend on the earth for sustenance.

We march because Sikh Gurus teach that there is no duality between the force which makes a flower grow and the petals we are able to touch and sense with our fingers.

We march because the Sikh Gurus referred to the Earth as a ‘Dharamsaal,’ a place where union with the Divine is attained. Guru Nanak describes this in Jap Sahib, that amid the rhythms of Creation, the changing seasons, air, and water, the Creator established the earth as the home for humans to realize their Divinity in this world.

This past weekend was pride weekend in my home of New York City and many other cities around the country and world. I missed many of the festivities because I was traveling but did attend the annual Trans Day of Action last Friday, a march a rally organized by the Audre Lorde Project and many other groups on the historic Christopher Street Pier. It was a beautiful gathering of a very diverse and energetic group of queer people, trans people, and allies. The event was largely led by LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) people of color and immigrants, a breath of fresh air given how these individuals are so often invisible/marginalized/excluded in both the mainstream gay movement and in their own communities and families.

Towards the end of the rally, a young desi man came up to me, introduced himself, and asked me about local Sikh activist groups to get involved in. He, like so many others in our community, has not found a Sikh space where he can take action on the various social justice issues he is passionate about — including LGBT rights and justice. We had a nice, short conversation about the activist roots of Sikhi and our Gurus’ radical commitment to equality and liberation. Yet we are all too aware of the rampant homophobia in our community, which I have written about before.

Given this reality, I was happy to see a PSA circulating in the last few days that features a Sikh family speaking out against homophobia. We could certainly use one in Punjabi to reach more members of our community, but this Hindi video is a great start nevertheless.

4) PSA Hindi from Asian Pride Project on Vimeo.

A few weeks ago, I was invited to participate in a planning and brainstorming retreat for an innovative pilot project that Union Theological Seminary is launching this summer. UTS, which has a longstanding commitment to social justice, are aiming to bring together a group of 30 young(ish) (21-35 year old) leaders from different religious and spiritual backgrounds for five days in New York City this July to explore the intersection of faith and justice and build a stronger spiritual activist movement together.

The Millennial Leaders Pilot Conference will take place July 13th to 17th at UTS in Manhattan. All travel and room and board expenses will be covered for participants, who should have histories of doing social and economic justice work in their respective communities. According to the conference website, applicants “may be community organizers, staff of NGO/NPO, in ordained or lay service to a local church or religious community, as well as they may function is less official leadership roles. Formal affiliation with a specific religious tradition or community is not a prerequisite and people with no affiliation are encouraged to apply. In this regard, the only formal requirement is an interest in the intersection between spirituality and activism.”

This promises to be an exciting and unique gathering with the potential of building a more long-term, sustainable movement of activists and organizers from different faith traditions. At the planning retreat, many of us discussed how questions of spirituality and religion are so often left out (or are even taboo sometimes) in progressive social and economic justice spaces. And on the other hand, which we often discuss here at The Langar Hall, social and economic injustices are so often perpetuated in the name of religion, including Sikhi.

If these ideas resonate with you, I hope you’ll consider applying and spreading the word to your friends, family, and colleagues, Sikh and non-Sikh alike. All the details about the conference and the application can be found here. The deadline to apply is the end of the day this Friday, May 23rd.

When most of us imagine what the people inside immigration detention centers in the United States look like, we usually do not  think of Sikhs from Punjab. Our Sikh American community — and more broadly South Asian American community — has been reluctant to deeply engage with the harsh realities of immigration policy and detention here in the United States. Too often we have seen this as someone else’s issue or passed quick judgment on those migrants from various parts of the world who overstayed their tourist visas or crossed the border under the radar — in search of work, to feed their families, in hopes of a better life. Papers or not, this hope for freedom is what brings all migrants to the United States.

think of Sikhs from Punjab. Our Sikh American community — and more broadly South Asian American community — has been reluctant to deeply engage with the harsh realities of immigration policy and detention here in the United States. Too often we have seen this as someone else’s issue or passed quick judgment on those migrants from various parts of the world who overstayed their tourist visas or crossed the border under the radar — in search of work, to feed their families, in hopes of a better life. Papers or not, this hope for freedom is what brings all migrants to the United States.

Right now at least 37 Punjabi migrants, who fled India in search of this illusive freedom, are detained in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in El Paso, Texas. News of these men and others at the El Paso facility protesting their indefinite detentions (they have been detained for over nine months now) came to surface in December. Last week, we learned that 37 Singhs — now known as the El Paso 37 — began a hunger strike.Â

37 young Sikh men — many who are seeking political asylum in the US — have been detained for almost a year in Texas, yet we have heard almost nothing about it in our organizations or gurdwaras. There has been no major news coverage of these men’s plight. Their harsh journey to El Paso reportedly took them through Moscow, Havana, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. Instead of finding respite, comfort, and safety in the US, they have found prison walls.

We Sikhs are celebrating ‪‎Vaisakhi this week, the 315th birthday of the Khalsa, a body of revolutionaries given the responsibility to tear down tyranny and oppression in all its forms. Hundreds of years ago, Sikhs had an intersectional analysis of oppression, recognizing that all forms of injustice were equally deplorable, whether based on caste, gender, economic class, or religion. Unfortunately today, we don’t always live up to this important ideal as a community as we so often perpetuate one form of subjugation while attempting to challenge another.

The last few days, I have been re-reading a bunch of feminist writing on the ways all forms of oppression are deeply interlocked in preparation for a workshop I am facilitating next weekend. I have long been inspired by women of color and Third World feminism and suddenly realized how related this all is to Vaisakhi — a moment when our ancestors formalized their commitment to Sikhi, to bridging the spiritual and political, to becoming freedom fighters, to initiating the Khalsa.

What follows is a passage from Marilyn Frye’s timeless 1983 essay, “Oppression,” which I find especially compelling when thinking about the necessity of understanding and challenging all forms of domination. This Vaisakhi, I am thinking about how these words connect to our struggle and path as a Sikh community.

The experience of oppressed people is that the living of one’s life is confined and shaped by forces and barriers which are not accidental or occasional and hence avoidable, but are systematically related to each other in such a way as to catch one between and among them and restrict or penalize motion in any direction. It is the experience of being caged in: all avenues, in every direction, are blocked or booby trapped.

Cages. Consider a birdcage. If you look very closely at just one wire in the cage, you cannot see the other wires. If your conception of what is before you is determined by this myopic focus, you could look at that one wire, up and down the length of it, and be unable to see why a bird would not just fly around the wire any time it wanted to go somewhere. Furthermore, even if, one day at a time, you myopically inspected each wire, you still could not see why a bird would have trouble going past the wires to get anywhere. There is no physical property of any one wire, nothing that the closest scrutiny could discover, that will reveal how a bird could be inhibited or harmed by it except in the most accidental way. It is only when you step back, stop looking at the wires one by one, microscopically, and take a macroscopic view of the whole cage, that you can see why the bird does not go anywhere; and then you will see it in a moment. It will require no great subtlety of mental powers. It is perfectly obvious that the bird is surrounded by a network of systematically related barriers, no one of which would be the least hindrance to its flight, but which, by their relations to each other, are as confining as the solid walls of a dungeon.

A few weeks ago, the Indian Supreme Court re-criminalized sexual acts between consenting adults of the same sex. The Supreme Court  overturned a 2009 decision by the Delhi High Court to strike down section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which came directly from a British colonial law from 1861. Section 377, which was just reinstated, states:

overturned a 2009 decision by the Delhi High Court to strike down section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which came directly from a British colonial law from 1861. Section 377, which was just reinstated, states:

377. Unnatural offenses — Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.

As Prerna Lal states about the recent ruling, “the Indian Supreme Court has re-criminalized gay sex in India, rendering almost 20 percent of the global LGBT population illegal.” As a result, LGBT Indians and their allies in India and around the world have taken to the streets, signed petitions, and engaged in creative actions through social media, showing their outrage about this backwards decision.

But what has the Sikh response been? I have previously written about the homophobia rampant in our community and how ironic it is, given our Gurus’ deep commitment to equality and social justice. In the days after the ruling on 377, I wondered if any Sikh activists committed to LGBT equality would come out of the woodwork. I also wondered about the Sikh response to the ruling in India and if any Sikh institutions publicly supported or lobbied for this ruling. Embarrassingly, Sikh institutions have publicly campaigned against LGBT equality in the past, including supporting the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in the US a few years back.

Enter Kanwar Saini, aka Sikh Knowledge, a young, openly gay hip hop artist in Toronto. In protest of 377 and as a part of a social media campaign, Saini posted a photograph of him kissing another man on Facebook, which went somewhat viral and led to a lot of discussion and debate about Sikhi and gay rights. Facebook removed the photo from his page for 16 hours, quite possibly due to a whole lot of homophobic Sikhs reporting the picture to Facebook as offensive.

Saini recently appeared on CTV discussing the incident and his response.

BREAKING NEWS: The Sikh Art and Film Foundation has responded by including a female speaker in next week’s Leadership Summit!!! Great progress. Â Yet, the lack of representation of women and girls from 2004 – 2012 in the film festivals and galas still needs to be addressed, and this is a community wide issue. Â See below for actionable solutions.

Via Email:

November 15, 2013 7:43PM Nina Chanpreet Kaur,

Dear Sikh Art and Film Foundation,

I am very glad to see that Rashmy Chatterjee will be speaking at next Friday’s Leadership Summit.  This is a tremendous gain for our community as most of the speakers at the summit have been men since 2011.  This represents a trend in many Sikh organizations I hope we can change together. As a Sikh woman and resident of NYC for the last 11 years, I have followed your organization since it’s inception.  Over the years, I have attended many of your events and have been so inspired by the films, speakers and attendees.  I have also noticed the lack of representation of women and girls in your programs.  Though you took a step forward this week, I believe you could be doing more to address, highlight and celebrate the challenges and triumphs of Sikh women and girls whether in your Film Festival, Heritage Gala or Leadership Summit.

I understand that your goal is to transcend the dichotomies and binaries of gender and other categories to sustain the universality and equality that our Gurus envisioned in order to promote and preserve Sikh and Punjabi heritage. Â I share your vision and do not condone a gender binary or bias towards either men or women. Â I am also aware that you face limitations as all organizations do, in particular that you must base the selections of films on the submissions you receive. Â However, Sikh men and boys have been a central part of your programs in a way Sikh women and girls have not and this indicates a bias – whether intentional or not.

From 2007 to 2012, none of your Gala awards for Leadership and Vision have been presented to Sikh women. Â In fact, the only women who received awards were for Creativity/Art with the exception of Shonali Bose who received an award for Courage and Shelley Rubin who received an award for Leadership jointly with her husband. Â For 5 years in a row you have only presented Sikh women with awards for Creativity/Art and no other category. Â As a Sikh woman, this sends a message to me and the next generation of Kaurs that women can be honored for creativity and art but not for leadership and vision. Â It raises questions about your beliefs and assumptions related to gender roles and women’s capacities in relation to men. Â This is most certainly not the message young Kaurs should be receiving, nor do I think this is your intention based on the email I received from Ravi last week. Â Â Â Â (more…)

There are only a few days left in the annual SikhNet Youth Online Film Festival. Â This year’s theme, “onKaur: Focusing the Lens on Women”, brings together a collection of 18 films by and about Sikh women. Â The films look at the idea of “Kaur”, what that means and how it can be represented in film.

There are only a few days left in the annual SikhNet Youth Online Film Festival. Â This year’s theme, “onKaur: Focusing the Lens on Women”, brings together a collection of 18 films by and about Sikh women. Â The films look at the idea of “Kaur”, what that means and how it can be represented in film.

The films have been categorized as documentary (“think”) and drama (“cry”) with issues including: Anand Karaj, bullying, hair, health issues of Panjab, gender justice, family, and gatka among others.

The film festival is important for several reasons and this year’s theme brings to light the need to include Sikh women’s voices in conversations around identity and community. Â It’s a valuable way of showcasing issues affecting Sikh women.

Here’s how to view and vote:

The film festival also provides a platform for young filmmakers to showcase their films to a wider audience.

1. View the documentary films here and vote via Facebook.

2. View the drama films here and vote via Facebook.

Voting ends on October 9th.

Guest Blogged by Jaideep Singh

As the Sikh American community embarks yet another mobilization against hate attacks— since this latest episode of violence has really hit home with many Sikhs in a way rarely seen since Balbir Singh Sodhi— we would do well to first answer the difficult, necessarily critical questions posed by my sister Nina Chanpreet Kaur in her thoughtful, passionate piece from last year.[1]

Our efforts at “education and outreach†clearly have yielded perilously little success— as measured by the safety of our communities. So education obviously is NOT enough. Reality is far more complex and ugly. A person who would attack a gurdwara is not coming to an open house or community feeding (langar) to abate their hatred. The long list of those in our communities who have been injured and killed, and the homes and gurdwaras defaced, testifies to as much. We cannot advance by hiding in our gated communities, far from the raw racial realities daily faced by our less fortunate sisters and brothers.

Fighting centuries of entrenched, utterly irrational white [and Christian] supremacy is neither an easy task, nor a short term one. Many of us cannot even bring ourselves to admit these forces even exist, let alone how they permanently define Sikhs as racial and religious outsiders. That naïve approach must end, replaced by a sophistication borne of serious historical study of U.S. history.

Sometimes I wonder where 1984 went

Sitting across the dinner table from my parents

Frozen

Me stuck at the age of 1

The annihilation of my mind

I touch my long braid to make sure it’s still there

My brothers dressed as girls to pass through another village for safety

Terror rises

And I dance

Making ancient sounds with my body

Slapping my heels against bare earth

Raising my arms then spinning

I look down at dirty red brown

The Junior Sikh Coalition is an initiative of the Sikh Coalition to help develop leaders in local communities, providing young Sikhs with experience in organizing, advocacy, diversity education and civil rights.

The Junior Sikh Coalition is an initiative of the Sikh Coalition to help develop leaders in local communities, providing young Sikhs with experience in organizing, advocacy, diversity education and civil rights.

In a new project, the Junior Sikh Coalition is harnessing the power of art in advocacy with an unprecedented art collection called the Nirbhau Nirvair Poetry & Art Book to bring attention to issues such as bullying and hate crimes. Young Sikhs across to country are invited to submit their art, poetry, and photographs, to showcase their perspective on the concept of Nirbhau Nirvair (“without fear and without hatred”), as first proclaimed by Guru Nanak in Jap Ji Sahib.

Find out more below about this unique opportunity for young Sikh artists.

I’ve been invited to and participated in a number of interfaith gatherings, conferences, retreats, and discussions over the years. Time and time again I find myself being the only Sikh in these spaces. And often find that the well-meaning, progressive faith-based activists in these spaces don’t know other Sikhs besides me nor do they know much about Sikhi. So then it was refreshing to hear about the 2030 Faith in America Challenge, an interfaith gathering to strategize around creating a more just society, from a Sikh friend who is helping organize it. On October 6-7, the Nathan Cummings Foundation will host leaders in the 20s and 30s for a retreat in upstate New York to explore important and urgent questions around religious diversity. The application deadline is Monday, July 15th! Check it out and consider applying. Sikh voices are greatly needed in this discussion.

More information follows, and visit the website here.

In a rapidly changing world, where faith is as often a force for inspiration as well as polarization, how might we as people of faith, support individuals and communities connected to their religious and spiritual identities, to amplify their voice, vision and public leadership?

Is this a challenge that resonates with you or keeps you up at night? Would you invest four days of your life to wrestle with this challenge with a diverse group of leaders?

If yes, we invite you to complete an application to join us for the 2030 Faith in America Challenge gathering application due on by Monday, July 15, 2013. If selected, travel, food and lodging will be covered by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Below you will find the articulation of the broader context in which we are locating this challenge, our belief in the importance of a strong religious and spiritual voice in the public arena, information about outcomes, methodology, profiles of potential participants, and a Frequently Asked Questions section.

Please review the required preparation and questions and please submit the completed application online by 11:59pm EST on Monday, July 15, 2013. Please send questions to 2030Challenge_FIA@nathancummings.org.

Guest blogged by CitizenSoulja, follow him on twitter at @citizensoulja

Guest blogged by CitizenSoulja, follow him on twitter at @citizensoulja

This year I went to the Lalkaar 2013 conference in Davis California. Lalkaar run by the Jakara Movement, a Sikh youth organisation, is now in its 14th year. This was by far the most interesting and inspiring Sikh educational event I have ever been to. Like many young Sikhs that grew up in the UK I failed to engage with the local Gurdwara, when it came to learning about Sikhi in an inclusive and non-judgemental environment. This gap in learning was filled by Sikh youth camps that sought to connect Sikh youngsters with the philosophy of the Sikh Way, but these too had their drawbacks.

I came across the Jakara Movement on social media and my first impressions were of a progressive, interesting and established organisation. I remember when I first saw Lalkaar advertised I really wanted to go but it wasn’t possible. When I began planning my travel to the States this summer my plan was to attend Sidak, a two week intensive Sikh Studies course run by SikhRi in San Antonio, I had no plans of coming to Lalkaar.

I spoke to my friend Narvir, who had attended Lalkaar previously and he had only positive things to say, I began seriously considering attending. My biggest worry was having a place to stay after Lalkaar. After I spoke to some of the sevadars, they connected me with other individuals that said they could house me. That’s when I packed my bags.

Christina Antonakos-Wallace, filmmaker of with WINGS and ROOTS

Christina Antonakos-Wallace is the filmmaker behind with WINGS and ROOTS, a 90-minute documentary that tells the stories of five people from different immigrant communities living in New York or Berlin, Germany, who have struggled to shape their identity in various ways.

The film features The Langar Hall’s own Sonny Singh, a Sikh living in New York. Part of his story was featured in the well-received short documentary Article of Faith, spawned from the with WINGS and ROOTS project, that portrays Sonny’s activism around bullying of Sikh school children in New York. Another short film, called Where are you from from? was also produced out of this project.

Below, Christina Antonakos-Wallace discusses the film and provides great insight about its intended message regarding the immigrant experience and the search for identity. You can view the trailer for with WINGS and ROOTS at the end of this post.

Guest blogged by Herpreet Kaur Grewal

Editorial note:Â the author talked to her colleagues on the Sikh Feminist Research Institute’s editorial board about why they are feminists. This blog post collects their views to mark the Sikh festival of Vaisakhi, which took place this weekend.

When you hear the words ‘Sikh feminist’ what images does it bring to mind? Perhaps it evokes a general image of Asian women holding placards and angrily protesting? Or maybe it reminds one of a grand warrior saint like Mai Bhago riding her horse into battle? Or possibly a more contemporary incident comes to mind, like the one of Balpreet Kaur who last year deflected taunts from an Internet troll by eloquently explaining why she decides to keep her facial hair in a society where women are largely pressured to be perfectly formed and hairless. Or maybe it evokes none of these images.

As editorial board members of a Sikh feminist body we feel compelled to express our philosophy as a proactive and empowered one. All of us look to the Sikh (and non-Sikh) values of equality, honesty and strength (among many others), to anchor our lives in an everyday spirituality. But that doesn’t mean our motivation has always rooted from a positive place.

One of us was sexually assaulted which absolutely shattered a personal notion that being strong, assertive and smart can keep you insulated from an attack. If anything, it laid bare the vulnerability that exists if you happen to be born a woman in a world that can devalue one so extremely and how that devaluation is integrated into the culture and system we live with. A culture and system which many men and women internalise – sometimes, to a massive extent.

“Indians, many of whom were Sikh, worked at the Hammond Mill before its demise in 1922. During that time period, the Indians left their mark on Astoria, participating in wrestling matches, occupying Alderbrook also known as “Hindu Alley,” and forming the Ghadar political party. Courtesy of Clatsop County Historical Society.” (source: The Daily Astorian)

One of the legacies of the earliest Sikh and Indian immigrants to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century was the creation of the Ghadar Party, a political movement based in northern California that sought to promote India’s liberation from British rule.

Led by Indian expatriates in the United States, the Ghadar Party was formed in 1913. One of its main activities was the publishing of literature to promote resistance to British rule and for a free India. Obviously a threat to the ruling class, the literature was banned in India, and upon their capture, the Ghadarites were often imprisoned or executed as terrorists by the British.

This year, the San Francisco headquarters of the Ghadar Party has been opened to the public by the Indian Consulate as a museum. The printing press that the Ghadar Party used to print their literature is also now on display at the Gurdwara in Stockton, California. However, while it was previously believed that the Ghadar Party was founded in California, historians now place the genesis of the movement further north in the state of Oregon, where Johanna Ogden recently mapped a forgotten (and primarily) Sikh settlement of laborers in 1910 known as “Hindu Alley”.

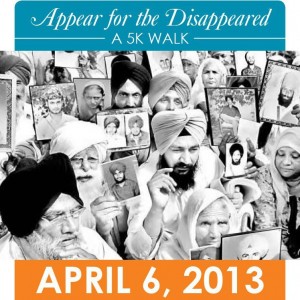

You will be walking in memory of twenty-eight-year-old Darshan Singh who was a young farmer from Amritsar district. On 9 September 1990, Darshan and two other young men went for a motorcycle ride when a group of police officers suspected them of being militants and shot at them. Darshan, the pillion rider, was hit by a bullet and fell down dead. The police took Darshan’s two companions into custody and reported them dead in alleged encounters.

After recently registering for Ensaaf’s Appear for the Disappeared 5K walk, I received the above email with information about the individual in whose memory I would be participating.

After recently registering for Ensaaf’s Appear for the Disappeared 5K walk, I received the above email with information about the individual in whose memory I would be participating.Ensaaf has documented thousands of cases of disappearance and unlawful killings in Punjab and in an effort to allow its supporters to connect with victims, Ensaaf is holding a 5k walk, called Appear for the Disappeared, on April 6, 2013 in Fremont, CA. The walk is an opportunity for all participants and virtual donors to commemorate a specific individual who was disappeared in Punjab by Indian security forces from the mid-1980s to late 1990s. Ensaaf’s goal is to commemorate 500 individuals and raise $25,000 to complete documentation efforts.

Between 1984 and 1995, Punjab witnessed thousands of disappearances and unlawful killings, with many victims facing unimaginable torture at the hands of Indian security officials. Rarely were victim families informed of the fate of their loved ones, let alone given a chance to carry out final rites and funeral services. As thousands of men and women disappeared and their families left in the darkness, responsible security officials were awarded promotions and their human rights violations faded into darkness.

Co-blogged by Sundari and The Sikh Love Stories Project

Each year, International Women’s Day is celebrated to honor women’s economic, political and social achievements. As individuals around the world celebrate this day – in both big ways and small – I am left to consider how we can work to honor the achievements of Sikh women not only today but on an ongoing basis.  Sikh women have contributed in such meaningful ways, and yet much of that dialogue is often missing from our history.

In this post, we will be sharing some images with you and discuss various ways Sikh women have been witness to and engaged in our history both locally and globally.  We know this post will not be comprehensive – there is much to unearth about Sikh women’s contributions – but we hope it’s a starting point that will encourage us to keep this valuable history in our minds. Many of the following images each depict a different element of Sikh women in history.

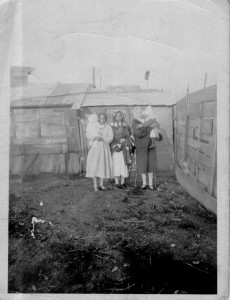

Stories often begin with immigration and this first image shows Sikh women pioneers in Canada who were part of an immigrant labor force recruited in the early years of the twentieth century.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Canada’s largest mill community, Fraser Mills in New Westminster, BC, had between 200 and 300 Sikhs living and working there in 1925.

In this photograph from that period, three Sikh women stand in front of company houses at the mill. [link]

One of them wears a traditional embroidered shawl called ‘phulkari’. The phulkari played an important role in the lifecycle rituals of women in Punjabi villages at times of birth, marriage and death.

We love Sardar Fauja Singh. Â We really, really do.

On Sunday, Fauja Singh will run his final race in Hong Kong at the tender age of 101.  Jezebel recently covered Fauja Singh in a piece about  women’s rights, and just today Jordan Conn wrote a compendious and inspiring article for Outside The Lines on ESPN about Fauja Singh’s life and the “missing” Guinness Book of World Records title.  This article, along with stunning photographs, spread like wildfire on Facebook and Twitter today – reminding us just how much the world loves Fauja Singh and what he represents.

On the first day of training, Fauja arrived limber and energetic and dressed, as he believed was perfectly appropriate, in a dazzling three-piece suit. Harmander told him he needed a wardrobe change. After adamant protests, Fauja relented, ditched the suit and bought running gear. He showed up every day after that, building his routine around his training schedule. His mileage increased as the weeks passed. Race day arrived. After 6 hours and 54 minutes, 4:48 behind winner Antonio Pinto, Fauja crossed the finish line. At age 89, he was a marathoner. Soon, he would be a star.

We will be wishing you well on Sunday, Fauja Ji! Â Thank you for continuing to be such an activist and a positive soul and for reminding us of the importance of health and happiness.

– The Langar Hall

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.