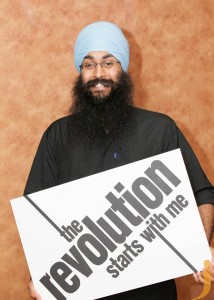

Guest blogged by Simran Jeet Singh

As I strolled outside my Manhattan apartment this morning, reflecting on the Trayvon Martin decision, I had one of those moments that would shatter any possible artifice of living in a post-racial society.

shatter any possible artifice of living in a post-racial society.

I heard a woman cry in pain and turned around to see her lying on the street, clutching her bleeding knee. I rushed over and extended my hand to help her up. She looked up and her entire body recoiled the moment she saw that my face was adorned with a turban and beard. She shook her head and muttered “foreigners…” just loudly enough so that I could hear. I stepped away, understanding her reaction, and I turned to hold the traffic as she gathered herself.

I watched her limp to the sidewalk and was surprised when she looked back at me over her shoulder and mouthed the words “thank you.”

And I realize now that I should have thanked her. She reminded me that despite being a social construct, race is absolutely real in our world, and in the rules of this game, so many of us find ourselves to be the typecast. It’s a lesson we receive repeatedly throughout our lives, but it bears repeating for a reason.

To forget the rules of the game is to forget the reality in which we live. As Keyser Soze said in The Usual Suspects, “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

I’ve been invited to and participated in a number of interfaith gatherings, conferences, retreats, and discussions over the years. Time and time again I find myself being the only Sikh in these spaces. And often find that the well-meaning, progressive faith-based activists in these spaces don’t know other Sikhs besides me nor do they know much about Sikhi. So then it was refreshing to hear about the 2030 Faith in America Challenge, an interfaith gathering to strategize around creating a more just society, from a Sikh friend who is helping organize it. On October 6-7, the Nathan Cummings Foundation will host leaders in the 20s and 30s for a retreat in upstate New York to explore important and urgent questions around religious diversity. The application deadline is Monday, July 15th! Check it out and consider applying. Sikh voices are greatly needed in this discussion.

More information follows, and visit the website here.

In a rapidly changing world, where faith is as often a force for inspiration as well as polarization, how might we as people of faith, support individuals and communities connected to their religious and spiritual identities, to amplify their voice, vision and public leadership?

Is this a challenge that resonates with you or keeps you up at night? Would you invest four days of your life to wrestle with this challenge with a diverse group of leaders?

If yes, we invite you to complete an application to join us for the 2030 Faith in America Challenge gathering application due on by Monday, July 15, 2013. If selected, travel, food and lodging will be covered by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Below you will find the articulation of the broader context in which we are locating this challenge, our belief in the importance of a strong religious and spiritual voice in the public arena, information about outcomes, methodology, profiles of potential participants, and a Frequently Asked Questions section.

Please review the required preparation and questions and please submit the completed application online by 11:59pm EST on Monday, July 15, 2013. Please send questions to 2030Challenge_FIA@nathancummings.org.

Guest blogged by CitizenSoulja, follow him on twitter at @citizensoulja

Guest blogged by CitizenSoulja, follow him on twitter at @citizensoulja

This year I went to the Lalkaar 2013 conference in Davis California. Lalkaar run by the Jakara Movement, a Sikh youth organisation, is now in its 14th year. This was by far the most interesting and inspiring Sikh educational event I have ever been to. Like many young Sikhs that grew up in the UK I failed to engage with the local Gurdwara, when it came to learning about Sikhi in an inclusive and non-judgemental environment. This gap in learning was filled by Sikh youth camps that sought to connect Sikh youngsters with the philosophy of the Sikh Way, but these too had their drawbacks.

I came across the Jakara Movement on social media and my first impressions were of a progressive, interesting and established organisation. I remember when I first saw Lalkaar advertised I really wanted to go but it wasn’t possible. When I began planning my travel to the States this summer my plan was to attend Sidak, a two week intensive Sikh Studies course run by SikhRi in San Antonio, I had no plans of coming to Lalkaar.

I spoke to my friend Narvir, who had attended Lalkaar previously and he had only positive things to say, I began seriously considering attending. My biggest worry was having a place to stay after Lalkaar. After I spoke to some of the sevadars, they connected me with other individuals that said they could house me. That’s when I packed my bags.

Christina Antonakos-Wallace, filmmaker of with WINGS and ROOTS

Christina Antonakos-Wallace is the filmmaker behind with WINGS and ROOTS, a 90-minute documentary that tells the stories of five people from different immigrant communities living in New York or Berlin, Germany, who have struggled to shape their identity in various ways.

The film features The Langar Hall’s own Sonny Singh, a Sikh living in New York. Part of his story was featured in the well-received short documentary Article of Faith, spawned from the with WINGS and ROOTS project, that portrays Sonny’s activism around bullying of Sikh school children in New York. Another short film, called Where are you from from? was also produced out of this project.

Below, Christina Antonakos-Wallace discusses the film and provides great insight about its intended message regarding the immigrant experience and the search for identity. You can view the trailer for with WINGS and ROOTS at the end of this post.

University of Massachusetts – Boston

Department of Counseling and School Psychology

100 Morrissey Blvd, Boston, MA 02125-3393

University of Massachusetts Boston

Researcher: Dr. Kiran S. K. Arora

Study: Religious Discrimination and Race-Related Stress among North American Sikhs.

We are interested in conducting research with Sikhs living in North America. The purpose of the study is to examine how experiences of religious discrimination and race-related stress may impact the relationships, mental health, and overall well-being of Sikhs. To gather this information, we are looking for individuals over the age of 18, who self-identify as Sikh, and are living in North America, to complete a set of anonymous questionnaires online.

This study hopes to contribute to a dearth of academic literature on Sikhs and their families. Your contribution is valuable, as it would provide insight for family therapists and other mental health professionals working with Sikh families. Your participation is strictly voluntary. Confidentiality is of utmost importance, and measures will be taken to protect your identity.

The purpose of this announcement is to alert you to the research project and invite you to ask any questions you may have about this project. You may contact Dr. Kiran S. K. Arora at Kiran.Arora@umb.edu if you are interested in participating, or learning more about the study. To learn more about the study or participate, you may also go to https://www.psychdata.com/s.asp?SID=153728.

In a process that took three decades, Sajjan Kumar, a leader in India’s Congress Party, was recently acquitted for his well-documented involvement in the anti-Sikh pogroms during November 1984 in which thousands of Sikhs were murdered in three days in the country’s capital city. Five co-accused were convicted. (Source: Live Mint)

About two months ago, I observed the continuing engagement by representatives of the Indian government with the Sikh American community, which in that instance took the form of an exhibition on Sikh heritage in Atlanta, Georgia, sponsored by the Government of India. This exhibit has just recently been presented in Washington, D.C., as well, and it is consistent with increased engagement and activity related to the Sikh American community — be it directly, or through lobbying of US officials — by representatives of India. The increasing effort by Indian officials to promote the Sikh community in the United States is problematic, however, as it runs contrary to India’s track record with the Sikhs in its own borders over the past several decades.

Whether in the aftermath of a hate crime (such as in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, or recently in Fresno, California), or in what appears a deliberate attempt to brand the Sikh identity with Indian nationalism, representatives of the Indian government are insisting that they be the custodians of the Sikh community in the United States.

Two of my fellow Sidakers from the class of 2012 have written wonderful blog posts that are succinct and tell you concisely what their Sidak experience was like. Please do give them a read: Santbir Singh on Sikhchic “Why I’ll Be There.” and Ruby Kaur on Sikhnet with the aptly titled, “Amazing Sidak.” It should come as no surprise that my post about my experience is long, but I’ve inserted photos to hide this fact.

Last July was a busy one for me. I attended a playwriting workshop in Cape Cod, and directly after that, it was off to Texas for two weeks of Sidak, an experience I still find difficult to put into words. It is officially:

“a distinctive leadership development program for young adults seeking to increase their commitment towards the Sikh faith. This two-week intensive immersion in Sikh culture, language, values and community though understanding bÄnÄ« (scripture), tvÄrÄ«kh (history), and rahit (discipline), is held annually in the Hill Country of San Antonio, Texas.â€

There is nothing I disagree with in their description, but to me it is much more than just those things. I first learned about Sidak from a blog post on TLH by Sharandeep Singh, and I was very enticed by the Gurmukhi course. So enticed, I applied, despite my initial reservations. Those reservations were primarily based on the fact that I didn’t fit into the perceived demographic I had pinged in my head as the sort of person who would attend Sidak. I’m not a Sikh active in my community (at least not in the conventional sense), the gurduara, or even someone who had grown up attending Sikh youth camps, except one year at Jakara when I was 30 (http://ow.ly/l2F6X). I’m in my mid-30s, occasionally go to the gurduara, and while I read, write, and speak Punjabi “relatively well,†I am not well versed in Sikh theological terminology. I had no idea what the difference between a tuk, a var, or a bani were, when they’d be used in class or during Divan.

In 1984, as the Indian government was terrorizing Sikhs in northern India, mass campaigns of state-sponsored extermination were occurring in the Americas as well. The small Central American nation of Guatemala, under the rule of US-backed Efrain Rios Montt, was one such place. While Indira Gandhi’s army was attacking Darbar Sahib with an insatiable thirst for Sikh blood, Guatemala was in the midst of what is sometimes called a civil war. Another name for it might be the deliberate and targeted mass killing of indigenous and poor people. In both cases, though thousands of miles apart geographically and politically, campaigns of state-sponsored genocide were underway.

Yesterday, a Guatemalan court found Rios Montt, now 86 years old, guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. He came to power in 1982 in a US-backed coup and oversaw “a scorched-earth policy in which troops massacred thousands of indigenous villagers. He entered the court on Friday to boos and cries of ‘Justicia!’ or justice. Prosecutors say Rios Montt turned a blind eye as soldiers used rape, torture and arson to try to rid Guatemala of leftist rebels during his 1982-1983 rule, the most violent period of a 1960-1996 civil war in which as many as 250,000 people.” (link)

Rios Montt awaiting the verdict in Guatemala. (source: New York Times)

The former dictator has been sentenced to 50 years in prison for genocide and 30 more from crimes against humanity. This is the first time in history that a head of state has been found guilty of committing genocide in his or her own country. The significance of this conviction cannot be overstated for the people of Guatemala as well as other parts of Latin America and the world where genocidal tyrants have never been held accountable for their atrocities.

What we’re not hearing much about in the US news coverage of this unprecedented trial is the US government’s role in Guatemala at the time (and earlier, beginning with the CIA coup against Arbenz in 1954, essentially for the benefit of the United Fruit Company). While there is much to celebrate in this conviction, key architects and underwriters of these policies of terror in Guatemala (and other parts of Latin America) have faced no consequences for their instrumental role in the genocide. Efrain Rios Montt was trained by the US Army at the school formerly known as the School of the Americas, infamous for training Latin American soldiers and leaders in the art of torture and repression. Rios Montt was close ally of the Reagan Administration, which considered his leadership style necessary in the so-called fight against communism. Revolutionary struggles were building in Nicaragua and El Salvador, and the Reagan Administration saw to it that they would be crushed as would anything or anyone that posed a real or perceived threat against multinationals corporations exploiting the continent’s rich natural resources. In practice, what this meant in Guatemala (and elsewhere) was if you are indigenous and/or poor, you must be a leftist and thus, you must be silenced, intimidated, and/or killed.

Sound familiar?

Many of us Sikhs and other South Asians in the diaspora have grown up with subtle and not so subtle messages of anti-black racism from our families and communities at large. While on the one hand we learn through Sikhi that all people are equal regardless of their race, caste, or gender, we simultaneously learn that we should not socialize with black people and certainly not date them. We learn they are not to be trusted, that we should keep our distance. We learn that they are unattractive and that we most certainly want to keep our (brown) skin as wheatish and fair and lovely as possible or else we might be called kala (which my Nana Ji used to jokingly call me, as I was the darkest in my family). I recall a family member bluntly telling me when I was a kid, “You can marry whoever you want when you grow up as long as she is not black.”

In his groundbreaking 2001 book Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting, Vijay Prashad explains the anti-black racism so pervasive in our ![]() communities:

communities:

But all people of color do not feel that their struggle is a shared one. Some of my South Asian bretheren…feel that we should take care of our own and now worry about the woes of others, that we should earn as much money as possible, slide under the radar of racism, and care only about the prospects of our own children…

Since blackness is reviled in the United States, why would an immigrant, of whatever skin color, want to associate with those who are racially oppressed, particularly when the transit into the United States promises the dream of gold and glory? The immigrant seeks a form of vertical assimilation, to climb from the lowest, darkest echelon on the stepladder of tyranny into the brightness of whiteness.

Guest blogged by Mewa Singh

Earlier this year the Center for South Asia at Stanford University along with the Jakara Movement hosted its 4th annual Sikholars Conference (see the recap here). Â This successful endeavor bringing the latest academic research with an engaged community audience allows for fruitful discussion and exchange. Â Not limiting this event only to California, Sikholars conferences and workshops have been previously held in British Columbia, Canada and now in London, UK. Â Teaming up with Queen Mary College, University of London and Singh Sabha Southall, the Jakara Movement is proud to present Sikholars London.

Earlier this year the Center for South Asia at Stanford University along with the Jakara Movement hosted its 4th annual Sikholars Conference (see the recap here). Â This successful endeavor bringing the latest academic research with an engaged community audience allows for fruitful discussion and exchange. Â Not limiting this event only to California, Sikholars conferences and workshops have been previously held in British Columbia, Canada and now in London, UK. Â Teaming up with Queen Mary College, University of London and Singh Sabha Southall, the Jakara Movement is proud to present Sikholars London.

For those in the UK (looking at you @Blighty), hope you get to check it out and experience Sikholars – London. Â For more information visit their website here.

Guest blogged by Herpreet Kaur Grewal

Editorial note:Â the author talked to her colleagues on the Sikh Feminist Research Institute’s editorial board about why they are feminists. This blog post collects their views to mark the Sikh festival of Vaisakhi, which took place this weekend.

When you hear the words ‘Sikh feminist’ what images does it bring to mind? Perhaps it evokes a general image of Asian women holding placards and angrily protesting? Or maybe it reminds one of a grand warrior saint like Mai Bhago riding her horse into battle? Or possibly a more contemporary incident comes to mind, like the one of Balpreet Kaur who last year deflected taunts from an Internet troll by eloquently explaining why she decides to keep her facial hair in a society where women are largely pressured to be perfectly formed and hairless. Or maybe it evokes none of these images.

As editorial board members of a Sikh feminist body we feel compelled to express our philosophy as a proactive and empowered one. All of us look to the Sikh (and non-Sikh) values of equality, honesty and strength (among many others), to anchor our lives in an everyday spirituality. But that doesn’t mean our motivation has always rooted from a positive place.

One of us was sexually assaulted which absolutely shattered a personal notion that being strong, assertive and smart can keep you insulated from an attack. If anything, it laid bare the vulnerability that exists if you happen to be born a woman in a world that can devalue one so extremely and how that devaluation is integrated into the culture and system we live with. A culture and system which many men and women internalise – sometimes, to a massive extent.

As you have probably heard by now, Boston is reeling in the aftermath of a few explosions near the Boston marathon this afternoon. Two people  have been killed and dozens injured and being treated at local hospitals. I’ve been texting, calling, and checking up on friends in the area all afternoon. We are all shook up and confused by what is happening, searching for answers or explanations for something so hard to comprehend (though something commonplace in other parts of the world like Pakistan, where 4 were killed by a US drone yesterday, and Iraq, where over 50 were killed in a bombing today). Very little is yet known about who did this and why, but of course, the mass media are already making lots of unsubstantiated claims, while accusations and assumptions are spreading quickly on Twitter and Facebook.

have been killed and dozens injured and being treated at local hospitals. I’ve been texting, calling, and checking up on friends in the area all afternoon. We are all shook up and confused by what is happening, searching for answers or explanations for something so hard to comprehend (though something commonplace in other parts of the world like Pakistan, where 4 were killed by a US drone yesterday, and Iraq, where over 50 were killed in a bombing today). Very little is yet known about who did this and why, but of course, the mass media are already making lots of unsubstantiated claims, while accusations and assumptions are spreading quickly on Twitter and Facebook.

As something as horrifying as this afternoon in Boston is literally unfolding, as we are worrying about loved ones who may be affected, we already have to worry about the consequences of backlash violence. We have to worry about the sensationalism in the media. We have to worry about being attacked because of the color of skins, the turbans or hijabs on our heads, the beards on our faces. I pray that people in the United States and beyond have learned something in the last 11 and a half years. I pray that the collective response to today will be drastically different from the knee-jerk racism that pervaded the days, weeks, months, and years after 9/11/01.

But honestly, I’m not so sure how hopeful I am.

“Indians, many of whom were Sikh, worked at the Hammond Mill before its demise in 1922. During that time period, the Indians left their mark on Astoria, participating in wrestling matches, occupying Alderbrook also known as “Hindu Alley,” and forming the Ghadar political party. Courtesy of Clatsop County Historical Society.” (source: The Daily Astorian)

One of the legacies of the earliest Sikh and Indian immigrants to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century was the creation of the Ghadar Party, a political movement based in northern California that sought to promote India’s liberation from British rule.

Led by Indian expatriates in the United States, the Ghadar Party was formed in 1913. One of its main activities was the publishing of literature to promote resistance to British rule and for a free India. Obviously a threat to the ruling class, the literature was banned in India, and upon their capture, the Ghadarites were often imprisoned or executed as terrorists by the British.

This year, the San Francisco headquarters of the Ghadar Party has been opened to the public by the Indian Consulate as a museum. The printing press that the Ghadar Party used to print their literature is also now on display at the Gurdwara in Stockton, California. However, while it was previously believed that the Ghadar Party was founded in California, historians now place the genesis of the movement further north in the state of Oregon, where Johanna Ogden recently mapped a forgotten (and primarily) Sikh settlement of laborers in 1910 known as “Hindu Alley”.

Guest Blogged by: JSD

Today, the government of India has once again proved why it’s claim to being the world’s largest democracy is laughable. Not to mention the media in India, which claims to be fair and democratic in nature, however, this is simply not the case. India’s media is clearly state run and its news outlets make stories that create divides within communities. Why am I saying all this?

Today, the government of India has once again proved why it’s claim to being the world’s largest democracy is laughable. Not to mention the media in India, which claims to be fair and democratic in nature, however, this is simply not the case. India’s media is clearly state run and its news outlets make stories that create divides within communities. Why am I saying all this?

Sadda Haq is a fictional movie based on real events surrounding the militancy era in Punjab during the 1980s and 1990s. Showing accounts of “false encounters†and police brutality, the movie aims to show why average citizens were forced to take up arms against the oppressive regime. The movie was set to release worldwide today on April 5, 2013. Although the Indian Government can’t ban the movie worldwide, the Punjab government did manage to ban the movie in Punjab and other parts of India in just a few hours prior to its opening after the movie was privately screened to Punjab Police members and state government officials.

These officials who watched the private screening included the likes of DGP Sumedh Saini. Interestingly enough, the ban comes from the Punjab government run by Parkash Badal of the Akali Party, a party that is supposed to represent Sikh interests, but at the same time has promoted Saini to the ranks of DGP(Deputy General of Police) even after countless human rights claims exist against him for his participation in the post 1984 Punjab genocide of Sikh youth.

Over the past few days the Indian news outlets have been talking about Sadda Haq being a controversial film promoting Khalistan. It is no doubt that Sadda Haq discusses the militancy era, but its aim is to show the truth that has been pushed under the rug by the government and media.

A North American based Internationalist movement for the liberation of India

Guest blogged by York Ghadaris

On the centenary of the Ghadar Movement, a conference is being held at York University, Toronto, Canada on April 12 to April 13, 2013, to honour and remember its history, and its contemporary relevance to the revolutionary struggle of people of the Indian subcontinent.

It has been 100 years since the Ghadar Movement was formed by emigrant Punjabis and other Indian nationals in San Francisco in 1913. The Ghadar Movement ranks alongside other revolutionary movements of the early 20th century. In common with revolutionary movements in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Black Liberation movements of North America, the Ghadar Movement opposed imperialist powers, colonialism, and strived to develop working class internationalism.

This conference is called, with the participation of approximately 18 scholars and activist from North America and the UK, to remember the Ghadar Movement, its historical development, and to analyze its contemporary relevance to the revolutionary struggle of the people of the Indian subcontinent. The conference will examine the Ghadar struggle as a journey from the 20th century, “a century of revolutionsâ€, to its role in laying the foundation stones for the revolutions of the 21st century. These revolutions are crystallizing in response to the imperialist occupations of Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Haiti, the air attacks on Pakistan and the possibility of NATO attacks on Iran and Syria. The economic meltdown of the European Union (EU) and North America resulting in mass unrest are adding to the cause of revolution. They are taking shape in the form of the Arab Spring, the ongoing revolutions in Venezuela, Nepal, and the emerging people’s struggles in India.

This March marked ten years since the United States invaded Iraq in the name of Iraqi freedom. Ten years later, potentially over one million Iraqi civilian deaths later, where are we now? What are the people of Iraq left with? Aside from extreme instability and near genocide, Iraqis are now dealing with a legacy of cancer and birth defects as a result of our country’s military aggression. A few weeks back on Democracy Now, journalist Dahr Jamail discussed this harrowing reality. He stated:

“[The birth defects] are extremely hard to bear witness to, but it’s something that we all need to pay attention to … What this has generated is from 2004 up to this day, we are seeing a rate of congenital malformations in the city of Fallujah that has surpassed even that in the wake of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that nuclear bombs were dropped on at the end of World War II.”

What follows is the clip from the news program. Note that the images in the clip are horrific. This is reality. This is our tax dollars at work.

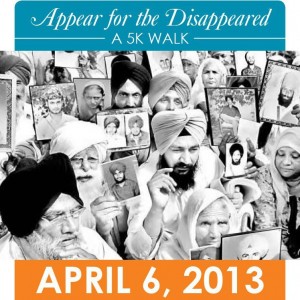

You will be walking in memory of twenty-eight-year-old Darshan Singh who was a young farmer from Amritsar district. On 9 September 1990, Darshan and two other young men went for a motorcycle ride when a group of police officers suspected them of being militants and shot at them. Darshan, the pillion rider, was hit by a bullet and fell down dead. The police took Darshan’s two companions into custody and reported them dead in alleged encounters.

After recently registering for Ensaaf’s Appear for the Disappeared 5K walk, I received the above email with information about the individual in whose memory I would be participating.

After recently registering for Ensaaf’s Appear for the Disappeared 5K walk, I received the above email with information about the individual in whose memory I would be participating.Ensaaf has documented thousands of cases of disappearance and unlawful killings in Punjab and in an effort to allow its supporters to connect with victims, Ensaaf is holding a 5k walk, called Appear for the Disappeared, on April 6, 2013 in Fremont, CA. The walk is an opportunity for all participants and virtual donors to commemorate a specific individual who was disappeared in Punjab by Indian security forces from the mid-1980s to late 1990s. Ensaaf’s goal is to commemorate 500 individuals and raise $25,000 to complete documentation efforts.

Between 1984 and 1995, Punjab witnessed thousands of disappearances and unlawful killings, with many victims facing unimaginable torture at the hands of Indian security officials. Rarely were victim families informed of the fate of their loved ones, let alone given a chance to carry out final rites and funeral services. As thousands of men and women disappeared and their families left in the darkness, responsible security officials were awarded promotions and their human rights violations faded into darkness.

While many people often confuse Vaisakhi as the beginning of the new year, today is the actual Sikh New Year.  It is the first day of the Nanakshahi Calender and Chet is the first month.  Today is also Sikh Environment Day, a campaign initiated by Eco Sikh and its volunteers throughout the globe and celebrated on the Gurgadi of Guru Har Rai Ji.

“Chet” from Barah Maha Calender

What will your new year’s resolutions be? Â What Sikh ideals will you plant today and seek growth of throughout the year?

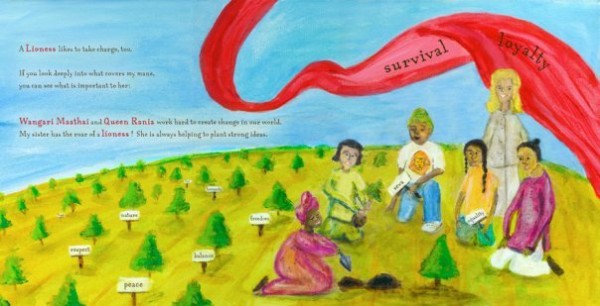

Image from “A Lion’s Mane”

Barah Maha Calender via Sikh Foundation

A Lion’s Mane by Navjot Kaur via Saffron Press

Co-blogged by Sundari and The Sikh Love Stories Project

Each year, International Women’s Day is celebrated to honor women’s economic, political and social achievements. As individuals around the world celebrate this day – in both big ways and small – I am left to consider how we can work to honor the achievements of Sikh women not only today but on an ongoing basis.  Sikh women have contributed in such meaningful ways, and yet much of that dialogue is often missing from our history.

In this post, we will be sharing some images with you and discuss various ways Sikh women have been witness to and engaged in our history both locally and globally.  We know this post will not be comprehensive – there is much to unearth about Sikh women’s contributions – but we hope it’s a starting point that will encourage us to keep this valuable history in our minds. Many of the following images each depict a different element of Sikh women in history.

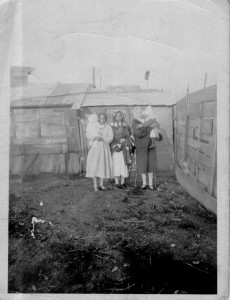

Stories often begin with immigration and this first image shows Sikh women pioneers in Canada who were part of an immigrant labor force recruited in the early years of the twentieth century.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Canada’s largest mill community, Fraser Mills in New Westminster, BC, had between 200 and 300 Sikhs living and working there in 1925.

In this photograph from that period, three Sikh women stand in front of company houses at the mill. [link]

One of them wears a traditional embroidered shawl called ‘phulkari’. The phulkari played an important role in the lifecycle rituals of women in Punjabi villages at times of birth, marriage and death.

Guest blogged: Mewa Singh

From February 16-17, 2013, researchers from throughout the world, focusing on Sikh-related topics, came together at Stanford University for the 4th annual Sikholars Conference, hosted by the Jakara Movement. From Europe to Pakistan, from India to Canada, and throughout the United States, young scholars came together for a weekend of discussion and engagement in a unique forum that connects the academy to the community. Here, I provide here a bit of a recap and encouragement for those that missed this year to make sure you don’t miss Sikholars 2014.

From February 16-17, 2013, researchers from throughout the world, focusing on Sikh-related topics, came together at Stanford University for the 4th annual Sikholars Conference, hosted by the Jakara Movement. From Europe to Pakistan, from India to Canada, and throughout the United States, young scholars came together for a weekend of discussion and engagement in a unique forum that connects the academy to the community. Here, I provide here a bit of a recap and encouragement for those that missed this year to make sure you don’t miss Sikholars 2014.

The conference commenced with an opening address by Professor Thomas Blom Hansen. The director of Stanford University’s Center for South Asia welcomed the audience and shared his excitement for a new partnership between the Jakara Movement and the Center for South Asia in years to come in hosting the Sikholars Conference.  Next followed a lecture by Professor Linda Hess, one of the world’s foremost authorities on Bhagat Kabir Ji.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.