Disclaimer for non-Sikhs: In writing this, I am not in any way saying Sikhs are somehow more predisposed to violence than any other community. The last thing I want to do is perpetuate racist stereotypes about Sikhs. However, I write because I see an opportunity for introspection in our community. If you choose to continue reading, I encourage you to think about how similar dynamics may play out in your community/ies.

I am still having a hard time wrapping my head around what happened in Newtown, CT last week, especially given the kind of year it has been here in the United States, from Aurora, CO to Oak Creek, WI.

For now, I want to pick up the conversation where Nina left off. Indeed, heartbreak is the right word for how I’m feeling about the deaths of children and adults due to gun violence, including those that don’t make the national news headlines, whether they are youth of color shot by police officers or families in Afghanistan bombed by the U.S. military.

Today, the depth and pervasiveness of violence in American culture is more clear than ever. The evening of the tragedy in Newtown, Michael Moore who made the Oscar-winning film about school shootings in 2002, Bowling for Columbine, stated:

I like to say that I sort of agree with the NRA when they say, ‘Guns don’t kill people, people kill people,’ except I would just modify that a bit and say, ‘Guns don’t kill people, Americans kill people,’ because that’s what we do. We invade countries. We send drones in to kill civilians. We’ve got five wars going on right now where our soldiers are killing people–I mean, five that we know of. We are on the short list of illustrious countries who have the death penalty. We believe it’s OK to kill you when you’ve committed a crime.

Guest Blogged by Nina Chanpreet Kaur

The year 2012 has been a series of heartbreaks. There is perhaps no greater pain than surviving a child. From Oak Creek, WI to the children whose lives were innocently lost in Newtown, CT and the millions of others who die as victims of violence every day, my heart breaks. So far, our response as a nation in the wake of Friday’s tragedy has been messy and presumptuous, but also clear and action-oriented at times. Deep pain, anguish, grief and conflict tend to have that affect: forcing us into action beyond our own daily lives and bringing us a greater sense of clarity.

In the wake of Sandy Hook, conversations about mental health, gun control laws and the root of violence in our schools, homes and communities continue to flash before our eyes. In response, we each do what we know best — for some it is grappling with a new world view to make space for such loss, for others it is taking time to grieve and release anxiety, and for several more it is taking quick action. So far, the Sandy Hook tragedy has transformed the views of some politicians and community members alike — Sikh Americans included. I am hopeful that this will bring increased attention and action to the problem of gun violence that also deeply affects the Sikh community.

The Sikh American community has responded to Sandy Hook by attending and organizing vigils across the country. A young Sikh boy imparted a beautiful message to the deceased children and national community, sharing his condolences. The Kalekas, who lost their father and members of their sangat to the tragedy in Oak Creek, have organized a movement around the film Nursery Crimes and met on Monday on the steps of City Hall in New York City along with Mayor Bloomberg and other politicians demanding gun control. They plan to travel with survivors from Oak Creek, Aurora and Columbine to Newtown, CT to lend a helping hand. Both Amardeep and Pardeep Kaleka have been instrumental in shining light on the roots of violence and hate and taking quick action. Producing several videos, erecting Serve 2 Unite and building a movement around Nursery Crimes are among a few of their many tremendous efforts. We need more Sikhs who are willing to speak up about the issue of gun control and systemic violence.

Guest blogged by Nina Chanpreet Kaur

August 5th, 2012. 1:33pm. A text message from my best friend: “hostage situation at sikh temple in wisconsin. on al jazeera right now.” We pulled over and exchanged glances, holding our breath it wasn’t an attack perpetrated by someone within the Sikh community. Earlier that morning we rowed in unison, kayaking down the Hudson. Her voice coaching my every movement. Later, riding side by side, we biked to the tennis courts. The wind blowing in our faces and trailing behind our backs, sheer joy and pleasure breezed through me. We had been riding our bikes home when we pulled over. After we said our goodbyes and went our separate ways, I went to hit some tennis balls. The news hadn’t yet sunk in. Once home, my entire being collapsed. I couldn’t avoid the flood of emails, messages and calls. I kept replaying the last few hours. The extreme contrast of the deep pleasure of my morning and the tragedy of Oak Creek felt like some sort of betrayal.

As the shock lifted and the news sunk in, I laid my forehead against the naked floor of my Manhattan apartment and wept. I wept for children, little bare feet hitting cement pavement running for safety. I wept for women crammed into a closet, gunshots threatening to penetrate their bodies. I wept for the pain of separation. I wanted to be there, I wanted to hold each of the bleeding victims in my arms. I wanted to sit next to Wade Michael Page. Make him stop. Have a conversation, maybe a cup of tea. I wept for the memories of the safe gurdwara that cradled me with kirtan as a child. Such a place no longer existed.

News from Wisconsin consumed me. Guilt. Grief. Why wasn’t I there? How does the universe exist in such extremes? At sunset, I picked myself up and started to write. I wrote emails. Long emails. I asked for a vigil. I planned a vigil. I wrote poems. I published them. I lost my appetite and any desire to eat, sleep or cook. I stayed awake through the night to organize. There was no such thing as comfort or rest for me in the weeks following Oak Creek. Heartbroken, the sadness cut through my very center. Organizing was my only way out.

Last week, two separate brutal attacks against Muslim men took place in Queens, New York. On November 24th, 72-year-old Ali Akmal was nearly beaten to death while going on his early morning walk and remains in critical, but stable, condition.

CBS New York reports:

Akmal’s tongue was so badly swollen that he couldn’t talk for two days. When he finally could, he told police that when he first encountered the two men, they asked him, “are you Muslim or Hindu?”

He responded “I’m Muslim,” and that’s when they attacked.

The beating was so savage and personal, Akmal was even bitten on the nose.

Just a few days earlier, 57-year-old Bashir Ahmad was beaten and stabbed repeatedly as he entered a mosque in Flushing, Queens early in the morning on November 19th. The attacker yelled anti-Muslim slurs at him, threatened to kill him, and also bit him on the nose. Ahmad was hospitalized and received staples in his head and stitches in his leg.

These vicious attacks come just a few months after the white supremacist rampage that left six Sikhs dead in Oak Creek, Wisconsin in August, followed by a string of at least 10 separate anti-Muslim attacks around the country in the two weeks that followed. And just over a year after the elderly Sikh men Gurmej Atwal and Surinder Singh were shot and killed on their evening walk in Elk Grove, California.

Needless to say, I was horrified last week when I heard about the attack on Ahmad and am even more horrified today after learning about Akmal,  a grandfather, nearly being killed in this act of violent hatred a few days later. The trauma of the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh for us Sikhs in, and there is little doubt that these recent attacks on Muslim men in Queens are rooted in the same type of bigotry that has so often made Sikhs targets since 9/11. As I’ve said before, our struggles are deeply connected.

a grandfather, nearly being killed in this act of violent hatred a few days later. The trauma of the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh for us Sikhs in, and there is little doubt that these recent attacks on Muslim men in Queens are rooted in the same type of bigotry that has so often made Sikhs targets since 9/11. As I’ve said before, our struggles are deeply connected.

The way I heard about the attack on Ahmad last week, though, was almost as troubling as the attack itself. I read this headline on NBC New York’s website: “Queens Mosque Stabbing Victim Says He’d Retaliate if Given Chance.”

Guestblogged by Mewa Singh

Few events are as anticipated as the annual Sikholars conference, held annually in the Bay Area. Now returning for the fourth year, the event continues to grow, generate new interest, and excite Sikh sangats from the Bay Area and beyond. A showcase for young Sikh scholars and others working on Sikh-related topics, the venue provides an intellectual space for engagement, discussion, and debate.

Few events are as anticipated as the annual Sikholars conference, held annually in the Bay Area. Now returning for the fourth year, the event continues to grow, generate new interest, and excite Sikh sangats from the Bay Area and beyond. A showcase for young Sikh scholars and others working on Sikh-related topics, the venue provides an intellectual space for engagement, discussion, and debate.

The conference has already announced its “call for papers”:

In anticipation of the fourth annual Sikholars: Sikh Graduate Student Conference, we are pleased to announce our call for papers. The Sikholars conference has attracted young scholars from over three continents and twenty–five universities. With topics ranging from Khalistan to Unix Coding, from sex-selective abortion to diasporic literature, from Nihangs in the court of Ranjit Singh to the North American bhangra circuit, from Sikh sculpture and architecture to representations of masculinity in Punjabi films, we encourage the widest possible range of those pursuing graduate studies on Sikh-related topics.

The deadline to apply to present is December 15, 2012.

The event is being hosted by Stanford University’s Center for South Asia and the Jakara Movement.

This past weekend, I attended the second annual Sikh Feminist Conference at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. A friend posted a concise review of the conference here which I would encourage you to read. I’ll just reiterate two points made – the first being the discussion around whether the western concept of Feminism fits within Sikhi. What does it mean to call oneself a Sikh Feminist or even a Male Sikh Feminist? Many participants at the conference felt the words “Sikh” and “Feminist” were redundant and that it was not necessary for us to try to mold to western definitions of feminism when our own faith clearly defines the concept of [gender] equality. On the other hand, others argued that the word is powerful enough to raise and question the issue of patriarchy that continues to exist within the community. The discussion reminded me of a similar conversation that was had at the Faith and Feminism panel, featuring Sikh women, which took place last year in NYC. About the panel discussion, the author writes,

The core values in Sikhism, particularly the human rights element, were what informed [the panelist’s] views on issues, including women’s rights. She has taken the word “feminism” out of the equation, and transplanted the values of it back into Sikhi, and reminded us that anyone who adheres to the principles of Sikhism and to the words of the Guru Granth Sahib has many labels, feminist, humanist, and activist are just some of them.

The second point is the important link between theory and practice within the Sikh community. I want to highlight this in two ways. The first being that while it has been established that the Gurus emphasized living in an eco-friendly way, it’s clear that as a community we are still working to close the gap – from melas to gurdwaras to within our own homes – our practice of living in an eco-friendly way could use some improvement. EcoSikh sponsored the Sikh Feminist conference and it’s presence was felt very thoughtfully throughout the day (biodegradable utensils, compost, recycling etc!) and it was inspiring to see our community not just talk about it in theory, but actually put it into practice.

Another discussion was around the concept of izzat or honor, whether it impacts both men and women, how it manifests differently for men and women and why it continues to be a topic of discussion when theoretically, our Gurus gave us the guidance and tools to live in an egalitarian society. The concept itself has been one of discussion on our blog too – particularly around what it means to a family and to a community. We are once again reminded of this issue with the recent news of Baljinder Kaur, a pregnant woman from Yuba City who was arrested over the weekend, just before the Sikh Women’s conference, for apparently killing her mother-in-law.

Guest blogged by Simran Jeet Singh

This past week, I visited a liberal arts college in Pennsylvania to introduce undergraduate students to the Sikh experience in America. I was pleasantly surprised to see that the professor had assigned Naunihal Singh’s piece from the New Yorker – “An American Tragedy” – one of the most insightful and well-written pieces published in the immediate aftermath of Oak Creek.

The professor had asked the students to submit short reflections on the shooting, and in reviewing their essays, I was struck by the consistent refrain that we have heard all too often: “If Wade Michael Page had only known that he was attacking Sikhs instead of Muslims…”

In other forums, I have discussed some problems with the framework of “mistaken identity,” including the implication of a “correct identity” to be targeted, the displacement of accountability, and the freezing of hate-violence within particular moments of time.

While I still stand by these arguments, I think there is a much more fundamental problem in our application of this idea to the shooting at the gurdwara in Oak Creek. We do not yet know Page’s specific intentions, yet we continue to assume that he actually intended to attack Muslims. For some reason, we have not seriously entertained the possibility that Page entered the gurdwara fully intending to kill Sikhs.

Guest blog by: Rocco

One of the highlights of fall in NYC is the Sikh Arts and Film Festival which showcases the story of our community via films and is being held November 2-3, 2012. Along with that is a Heritage Gala which is being held November 3, 2012 “to celebrate the rich heritage, culture and traditions of the Sikhs.” In the past dignitaries and business leaders have been selected as Chief Guest and Guest of Honors. Unfortunately, The Chief Guest this year is Nirupama Rao, India’s Ambassador to the United States and the Guest of Honors include Prabhu Dayal, Consul General India, New York and Hardeep Puri, India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

One of the highlights of fall in NYC is the Sikh Arts and Film Festival which showcases the story of our community via films and is being held November 2-3, 2012. Along with that is a Heritage Gala which is being held November 3, 2012 “to celebrate the rich heritage, culture and traditions of the Sikhs.” In the past dignitaries and business leaders have been selected as Chief Guest and Guest of Honors. Unfortunately, The Chief Guest this year is Nirupama Rao, India’s Ambassador to the United States and the Guest of Honors include Prabhu Dayal, Consul General India, New York and Hardeep Puri, India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

For some, Sikhs having Indian Government representatives as honorees poses no conflict and should be encouraged. One may argue that the attack on Darbar Sahib and Genocide in 1984 are distant events that occurred twenty eight years ago and should be forgotten. One may argue that the civil war which ensued for ten years afterwards in Panjab and led to the death of the tens of thousands of Sikh youth were collateral damage and justifiable in order to preserve the unity of India. One may argue that that struggle for an independent Panjab has reached its nadir and it’s important to “re-Indianize” ourselves and take advantage of the current economic environment.

Today is a federal holiday here in the United States — Columbus Day. Many of you probably share my disdain for the continued celebration of a man who helped kick off the colonization of the Americas and the genocide of indigenous peoples over 500 years ago, just as Guru Nanak was laying the groundwork for Sikhi to be born in Punjab. Gloating about his relentless pillaging, Columbus once stated, “I ought to be judged as a captain who for such a long time up to this day has borne arms without laying them aside for an hour.”

We Sikhs are truth-seekers and freedom fighters. Let’s stand with indigenous people throughout the Americas today, mourning those millions whose lives were taken by Columbus and the European colonizers who came after, and celebrating the spirit of resistance and quest for sovereignty which persist today throughout Turtle Island.

Yesterday’s news about the attack on KS Brar has excited, angered, inspired, and agitated many Sikhs throughout the world.

Yesterday’s news about the attack on KS Brar has excited, angered, inspired, and agitated many Sikhs throughout the world.

Many have questioned the Indian media’s initial assumption, before even the facts had arrived. Still others are wondering if the news is even factual. I have seen numerous postings on social media, believing that the attack was just a fabrication in order to make Sikhs appear ‘violent’ and ‘extreme’, especially after the recent goodwill expressed by some channels in the US and abroad after the recent Wisconsin Massacre. Finally, our brothers and sisters at Naujawani have written an intriguing article asking larger questions about a more sinister timing of all events (though not sure if I agree, well worth a read!).

I believe that the case of Kulbir Singh Barapind and Daljit Singh Bittu is extremely important, but that warrants a separate post. I will return to that issue at a future time.

Personally I am quite surprised that no names have appeared yet, as I figure someone would probably take credit and I wouldn’t imagine the names could be held a secret for too long within the community, especially if those that confronted him were young, as the claim is being made. Still I think that I want to take this conversation in a different direction. How do we ‘present’ SikhISM and its implicationsi?

Over the last month since the horrific tragedy in Oak Creek, WI, Sikh civil rights organizations and other leaders in the community seem to have come to a consensus on what our collective demand should be to move forward — getting the FBI to track hate crimes against Sikhs. A few weeks ago Valarie Kaur wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post entitled, “Sikhs deserve the dignity of being a statistic,” in which she convincingly articulates the basic argument that many are making:

The FBI tracks all hate crimes on Form 1-699, the Hate Crime Incident Report. Statistics collected on this form allow law enforcement officials to analyze trends in hate crimes and allocate resources appropriately. But under the FBI’s current tracking system, there is no category for anti-Sikh hate crimes. The religious identity of the eight people shot in Oak Creek will not appear as a statistic in the FBI’s data collection. As a Sikh American who hears the rising fear and concerns in my community, I join the Sikh Coalition and Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund (SALDEF) in calling for the FBI to change its policy and track hate crimes against Sikhs.

We’ve all probably gotten numerous action alerts to sign petitions, call our Senators, and, most recently, to attend tomorrow’s Senate hearing on hate violence in Washington, DC. The Sikh Coalition’s email advisory today about tomorrow’s hearing begins, “Be Present and Request that the FBI Track Hate Crimes Against Sikhs.”

It seems like a sensible request. The FBI is a government agency responsible for investigating hate crimes, so of course they should be looking specifically at attacks targeting Sikhs and have a category to enable them to do so. While I am sympathetic to this cause, I am a bit troubled by it, or have some questions about it, as well.

While I am not necessarily against the idea of a Sikh box for the FBI to check in the case of a hate attack against a Sikh, I am very skeptical of the FBI being an agency capable of working in the best interests of our community. To put it directly, I don’t trust them. And I’m not sure there is any reason for our community at large to trust them. Isn’t trust a prerequisite to inviting someone with a whole lot of power and resources into your homes, your schools, your houses of worship?

Co-blogged by Sanehwal and Mewa Singh

Co-blogged by Sanehwal and Mewa Singh

In an easily missed bit of North American Sikh intellectual bloodsport, IJ Singh and a graduate of UC Berkeley debated ideals about graduate education, the panth, and the academy. It is worth reading through for their different orientations towards the discussion, if at the very least to see how two people with very different positions in life (gender, education, class, age) interpret the issues at stake.

In IJ’s article, he mentioned the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, an American government program that funds graduate research. I had to Wikipedia it. At the time I was an undergraduate interested in applying to PhD programs in the social sciences, and despite the wealth of resources at my university, I ended up scouring the internet for advice on how to successfully apply to doctoral programs that routinely get upwards of 400 applications for 5 or 6 seats. The National Science Foundation’s graduate research fellowship was part of the deluge of items to tackle: letters of recommendation, emails to potential advisors, picking programs, and the dreaded statement of purpose. To make matters worse, my primary advisor was on leave, and unlike many of my peers, I had few friends or places to turn where I felt comfortable getting honest and expert advice on how to craft applications that best demonstrated my accomplishments and abilities.

The history of the Sikhs in the United States is known well in specific circles. Bhagat Singh Thind’s famous failed case for legal recognition by the US Supreme Court, iconic images of Stockton Gurdwara, traces of the Punjabi-Mexican experience, memories of the Ghadari Babas are generally remembered in this context. However, this is merely the tip of the iceberg.

The history of the Sikhs in the United States is known well in specific circles. Bhagat Singh Thind’s famous failed case for legal recognition by the US Supreme Court, iconic images of Stockton Gurdwara, traces of the Punjabi-Mexican experience, memories of the Ghadari Babas are generally remembered in this context. However, this is merely the tip of the iceberg.

A fascinating tale that is rarely discussed is that of Pahkar Singh. In our new post 9/11 fad to ad nauseam repeat that we are a “peaceful religion,” we tend to dismiss those heroic Sikhs that also faced racial discrimination in their own way. In the case of Pahkar Singh, the young Punjabi Sikh farmer living in the Imperial Valley (East of San Diego) in 1925. After being robbed of his crops and cheated by whites that took advantages of the racist laws in the land, Pahkar Singh picked up his gun and gandasa and killed two of them. He only stopped from killing a third, when the man’s 8 month pregnant wife, literally stood in the face of the barrel to protect her husband. At that point, Pahkar Singh turned himself in. At his defense, along with other Punjabi farmers, many even white small farmers came to sympathize with Pahkar Singh. He spent 15 years in San Quentin before he was released. It is these lesser known instances of the Sikh-American experience that I find so much more interesting.

In this vein, a number of Sikh organizations led by Stockton Gurdwara and the Sikh Information Centre have come together to host a series of events in celebration of the Sikh-American Centennial. Beginning on SEPTEMBER 22, , there are a series of events to commemorate, remember, and reflect on the Sikh-American focus. YOU DO NOT WANT TO MISS IT! With the recent events at Oak Creek Gurdwara, this may be a more prescient time than ever.

Guest blogged by Parvinder Mehta

Amidst the barrage and frenzy of shock and surprise and the discussions about why the Sikh community has been targeted and victimized through history, I wonder how Sikh parents have tried to make sense of the massacre of six Sikhs and the suicide of the gunman who came with his hateful agenda to the Gurdwara in Wisconsin earlier this month. “How can one human kill another human being on purpose?” I am always haunted by this question. As a parent, I shudder at the thought of violence creeping up in our lives. It is tough explaining to your children why some people commit heinous crimes against innocent people and why some people do not like Sikhs or may have never known about Sikhs. Or explaining why a Michigan Gurdwara was vandalized last year and how ignorance can be a dangerous premise.

Amidst the barrage and frenzy of shock and surprise and the discussions about why the Sikh community has been targeted and victimized through history, I wonder how Sikh parents have tried to make sense of the massacre of six Sikhs and the suicide of the gunman who came with his hateful agenda to the Gurdwara in Wisconsin earlier this month. “How can one human kill another human being on purpose?” I am always haunted by this question. As a parent, I shudder at the thought of violence creeping up in our lives. It is tough explaining to your children why some people commit heinous crimes against innocent people and why some people do not like Sikhs or may have never known about Sikhs. Or explaining why a Michigan Gurdwara was vandalized last year and how ignorance can be a dangerous premise.

I knew I must tackle the endless questions that they would ask about why someone committed this heinous act. I knew I must not use any rhetoric of hate or fear when talking to my children, the same way as my parents had taught me. Terms like prejudice, bias, racism, and ignorance are part of my children’s vocabulary much sooner than I had hoped. As a teacher and a parent, as a proud and practicing Sikh, I have always shared the anecdotes from Sikh history with my children where courage, not fear, is the driving lesson. The crucial question that we, as Sikh American parents, are faced is how we reassure our children that such hate-driven incidents will never recur. What can we do as Sikh parents to promise our children a hate-free environment so they can assert their Sikh identities without fear?

This election year is a reminder that Sikh Americans need to participate more actively in civic and political life. In order for the government and the media to pay attention to issues affecting our community, we need to have a seat at the table where decisions are being made and ensure that our voice is included in any policy changes.

The following are two ways that individuals can take action to change law that would impact the lives of Sikh Americans in California. These actions are for individuals living in California, but similar actions can and will take place in other states at various times. California is the 8th largest economy in the world, so if these changes become law – then these actions are even more meaningful for the Sikh community. It will go down in history that Sikh Americans helped create change for not just our own community but other marginalized communities too.

The following two bills have already successfully passed through both the California Assembly and Senate. Much of the hard work has been accomplished thanks to advocates within the Sikh community, sangat members across the state and Sikh organizations such as The Sikh Coalition. The final step in this process is for Governor Brown to sign these bills into law. You can help by taking one small step for each bill – by simply contacting the Governor’s office. While Governor Brown has until September 30th to sign these bills into law, he can decide on the bills any day. We encourage you to take action today! Please leave a comment in the section below letting us know if you have taken action.

AB1964 – Workplace Religious Freedom Act: SIGN THE PETITION

AB1964 – Workplace Religious Freedom Act: SIGN THE PETITION

If this bill moves forward and becomes law, it will sharply reduce job discrimination against Sikhs and other religious minorities and guarantee equal employment opportunity to all workers in California.

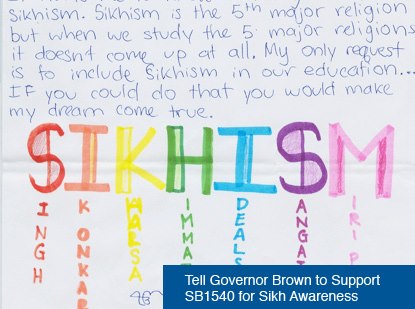

SB1540 – Revised Curriculum Framework: History-Social Science: SIGN THE PETITION

This bill would authorize the State Board of Education to complete the revision process of the History-Social Science Framework for California schools. When completed, this framework will ensure that California students learn about Sikhism and Sikh contributions, thereby increasing appreciation for diversity and reducing ignorance of the sort that leads to bullying and bias.

Guest blogged by Preeti Kaur

The following is an excerpt from Preeti Kaur’s poem “Letters Home,” in honor of those lost and injured in Oak Creek, WI. Read the full poem here, and sign the petition to push the FBI to track hate crimes against Sikhs.

i travel the 5th udaasi

i see no stranger in this country

when i was born my mother carried me

to richmond hill new york gurdwara to discover the first

letter of my name

as grown woman i perch above

pacific watch from el sobrante, california gurdwara

as fog rolls under golden

gate’s spine at sunset

i recite rehraas toward an angel island

100 year udaasi and i have traveled the whole country

hyphen is a language i lost

when the door to the Guru arrived

as asteroid from amritsar to stockton

Mian Mir put down the first brick

in the americas too

walt whitman spoke to 10 Nanaks

left his four directioned

pairs of shoes outside stockton’s darbar

shoes for us to borrow

in oak creek Bhai Taru Singh Ji’s scalp

lives again an eternal hair

which grows from 1907 bellingham

tied into the topknot of wisconsin

our kanga combs this hair with media soundbites

hair which absorbs perfume of flags

a mane we sometimes fear to wash

lakhi shah vanjara, mehar karo

give us your brave flame today

make our roof known as only nirbhao nirvair

hot winds blow away

with 5th Nanak’s naam we alight

this fire beneath us the first shaheed

a heat which ignites miri piri

for when they come for us

again

The news is still a shock. The question of “why” has been one that I have heard most often. Followed by “what next?”

The news is still a shock. The question of “why” has been one that I have heard most often. Followed by “what next?”

It is this second question that most interests me, as well.

The responses have been varied.

There are some that have called out that we are all American Sikhs, although most within the community would be a bit confused as most of us use the title “Sikh-Americans”, while the term “American Sikhs” is generally used for those sections in our community that often were first introduced to Sikhi by the late Yogi Bhajan.

There are others that are taking on the task to ‘teach’ others about Sikhi and raise talking points, when speaking to the media – either national or even regional. SALDEF and Sikh Coalition have been at the forefront and have even produced Sikhi 101-type materials that can be used when speaking to non-Sikh audiences. Both should be commended for their work.

Still far more interesting to me – and is often the case within The Langar Hall – is how Sikhs dialogue with each other. While still important – in some ways it seems a bit less significant how Sikhs speak to non-Sikhs, when compared to how we speak to one another. National attention will wane; the media will become bored; yet, we will still be there with one another. Two recent postings – one published on this very blog – largely speak to this very question.

Guest blogged by Santbir Singh

We are not strangers to random acts of violence and discrimination. Although mass shootings have become far too common in America in recent years, rarely have these horrific crimes been targeted at one community. Today, that changed. Our beautiful gifts, our kesh and dastars, have become easy targets for the ignorant and angry. Since 9/11 that discrimination has only increased. However, with the exception of the senseless killing of Balbir Singh Sodhi, these attacks have never been so deadly. Now Sikh Americans are left confused and uncertain of how to respond.

We are not strangers to random acts of violence and discrimination. Although mass shootings have become far too common in America in recent years, rarely have these horrific crimes been targeted at one community. Today, that changed. Our beautiful gifts, our kesh and dastars, have become easy targets for the ignorant and angry. Since 9/11 that discrimination has only increased. However, with the exception of the senseless killing of Balbir Singh Sodhi, these attacks have never been so deadly. Now Sikh Americans are left confused and uncertain of how to respond.

Our first priority must be the survivors and their friends and family. We are a generous community that is admirable in our response to tragedies. Seva is really nothing more than an act of love, a demonstration of recognizing the spark of the divine in others. Just as Guru Nanak sought to serve those in need wherever he traveled, we must reach out to our sisters and brothers in Oak Creek and demonstrate our support for them in every way conceivable. Whether this means monetary assistance, providing people on the ground, or offering support and understanding for the psychological trauma the Sangat of Oak Creek have suffered, a tragedy such as this provides us a unique opportunity to demonstrate our strength as a community.

Over the past 12 hours #templeshooting has been covering the twittersphere. It is a reference to the tragedy that occurred early this morning in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, where a gunman entered a Gurdwara during Sunday divan and killed six sangat members, wounding many more. Sikhs around the country reacted almost immediately to this event – posting updates on Facebook and Twitter, speaking to news outlets, filling in gaps of misinfomation, supporting Sikh organizations who have been working diligently with local officials and government agencies and community members who started up a fund for the families of the victims. While this has been an incredibly traumatic experience for the Sikh American community, we are inspired by the actions of the police officer who came to the aid of the sangat members – potentially preventing a larger massacre. We are comforted by the support of our friends and colleagues who have reached out to the Sikh community offering their solidarity.

Over the past 12 hours #templeshooting has been covering the twittersphere. It is a reference to the tragedy that occurred early this morning in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, where a gunman entered a Gurdwara during Sunday divan and killed six sangat members, wounding many more. Sikhs around the country reacted almost immediately to this event – posting updates on Facebook and Twitter, speaking to news outlets, filling in gaps of misinfomation, supporting Sikh organizations who have been working diligently with local officials and government agencies and community members who started up a fund for the families of the victims. While this has been an incredibly traumatic experience for the Sikh American community, we are inspired by the actions of the police officer who came to the aid of the sangat members – potentially preventing a larger massacre. We are comforted by the support of our friends and colleagues who have reached out to the Sikh community offering their solidarity.

Here we have started a running list of articles, resources and community gatherings. We hope this will be a way for you to learn about the events and about ways for you to stay engaged.

It has been nearly four years since we last attempted this. Back then, we attempted TLH’s very first book club, by examining Gurharpal Singh’s and Darshan Singh Tatla’s Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community. This round we are suggesting Vijay Prasad’s Uncle Swami.

It has been nearly four years since we last attempted this. Back then, we attempted TLH’s very first book club, by examining Gurharpal Singh’s and Darshan Singh Tatla’s Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community. This round we are suggesting Vijay Prasad’s Uncle Swami.

Although the book is aimed at issues centered around South Asian American experiences, it may be useful and enlightening to see how well they fit, shape, and interest Sikh-American experiences.

The Book:

From the jacket:

Within hours of the attacks on the World Trade Center, misdirected assaults on Sikhs and other South Asians flared in communities across the nation, serving as harbingers of a more suspicious, less discerning, and increasingly fearful worldview that would drastically change ideas of belonging and acceptance in America.

Weaving together distinct strands of recent South Asian immigration to the United States, Uncle Swami creates a richly textured discussion of a diverse and dynamic people whose identities are all too often lumped together, glossed over, or simply misunderstood. Continuing the conversation sparked by his celebrated work The Karma of Brown Folk, Prashad confronts the experience of migration across an expanse of generations and class divisions, from the birth of political activism among second-generation immigrants and the meteoric rise of South Asian American politicians in Republican circles to migrant workers, who are at the mercy of the vicissitudes of the American free market.

A powerful new indictment of cultural and racial politics in America at the dawn of the twenty-first century, Uncle Swami restores a diasporic community to its full-fledged complexity, beyond both model minorities and the specters of terrorism.

The Author:

For those interested in issues related to South Asian Americans, Professor Vijay Prasad needs little introduction. The author of The Karma of Brown Folks has been one of the foremost thinkers and scholars on the subject of identity politics and identity formation of South Asians in the Unitd States.

There has been plenty of criticism of his politics, book, and writings. All of these are pertinent and can allow for a more nuanced discussion. Still his voice is important and calls out for discussion.

The Format:

- Part 1 (Monday, 7/16) – Chapter 1 (Letter to Uncle Swami) and Chapter 2 (The Day Our Probation Ended)

- Part 2 (Monday, 7/23) – Chapter 3 (The India Lobby) and Chapter 4 (How Hindus Became Jews)

- Part 3 (Monday, 7/30) – Chapter 5 (Compulsions of Ethnicity) and Chapter 6 (The Honeycomb Comes Apart)

What to do from here:

- Order the book ASAP. Don’t delay as we are going to begin in one week.

- Invite others and help us spread the word!

- If you are going to participate, leave a short introduction here in the comment section and let us know that you plan to take part.

- Be ready in 1 week!