Part 3 – Sikh Book Club – Sikhs in Britain: Khalistan and Multiculturalism

Coblogged by: Jodha and Mewa Singh

Well it doesn’t seem by the number of comments (0) that this first attempt at a book club garnered much interest, although by the number of hits, it has been extremely popular. Regardless, for us it has been a  great excuse to read a great book….So we’ll continue. PS: the side picture is related to a soon-to-be-available coffee table photography book.

great excuse to read a great book….So we’ll continue. PS: the side picture is related to a soon-to-be-available coffee table photography book.

———————————————–

The two chapters read this week probably deserve separate blog posts, but still in the interest of time and space, we are going to keep them together.

Chapter 5 deals with “Homeland Politics: Class, Identity, and Party” and Chapter 6 is about “British Multiculturalism and Sikhs.”

The authors begin chapter 5 by noting that:

Associations of immigrants in Britain have generally served two functions: to facilitate the integration of the new arrivals and as conduits of homeland politics, and these functions have further strengthened with the onset of globalization, which has underpinned the rise of nationalism and diaspora movements. (94)

1984 is seen as the ‘critical’ event that intensified Sikh religio-ethnic self-identification with large numbers of Sikhs. The mammoth protest at Hyde Park on June 10, 1984 may still be vividly inscripted upon the memories of many Sikh-Britishers.

Still the associations and groups that were created to manifest this new religio-ethnic self-identification and homeland politics were along the lines of traditional associations. While there was something new in what came out of the community after 1984, there are continuities as well.

Tracing the evolution of various causes within the Sikh community, the authors note moves from the politics of class (IWAs [Indian Workers Association] up to the early 1980s), to the politics of identity (Khalistan 1984-1997), to emphasis on political organization (Sikh Political Party, UK) (94).

Still, it is important to note that such distinctions should not be overly emphasized as both ethnicity and class remained conjoined. The IWA was an ethnic organization and Sikh identity politics has distributionist aims.

Some interesting observations on the post-1984 organizations that have continuities with previous attempts:

- No parties are horizontal in structure, but essentially vertical with a ‘leader’ that has linkages to various patronage networks.

- All parties are based on factionalism, but factionalism assures these organizations have a short lifespan, despite multiple incarnations and grandiose titles (95)

- As institutions have failed to evolve, Sikhs and Sikh organizations can only rally behind single-issue causes.

One fascinating contrast that the authors highlight was the diversity within the category of Khalistanis, including their approaches. One such contrast was between the Council of Khalistan (COK), and the Babbar Khalsa (BK) and International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF). While the COK represented the movement’s first phase, they established a separate office as a headquarters;the ISYF and BK largely operated within the Gurdwara.

So our first question is: leaving aside these Khalistani organizations, what is the relationship between Sikh organizations and the Gurdwaras that we are seeing manifest today? Are they as intricately linked? What are the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches?

The authors later discuss the various outcomes in Britain of the post-1984 mobilization. While Sikh nationalists had some successes, they had many failures as well. The Indian State was more than adept at seeing that its interests were preserved. The Extradition Treaty signed in September 1992 between the UK and India was criticized by many human rights activists as the selling out of human rights by the UK government in order to secure future arms deals and trades with India.

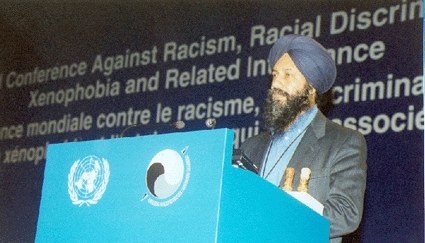

With the failure of Sikhs to achieve their homeland for now, the resources and people politicized and mobilized have transformed their aims. One particular success was the expanded definition of racism by Sik h Human Rights’ Dr. Jasdev Singh Rai and other Sikh groups that lobbied at the United Nations’ World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance (WARC) in Durban, South Africa, where article 67 of the final conference declaration recognized:

h Human Rights’ Dr. Jasdev Singh Rai and other Sikh groups that lobbied at the United Nations’ World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance (WARC) in Durban, South Africa, where article 67 of the final conference declaration recognized:

that members of certain groups with a distinct cultural identity [like the Sikhs] face barriers from the complex interplay of ethnic, religious, and other factors as well as their traditions and customs and call upon states to ensure that measures, policies and programmes aimed at eradicating racism, racial discrimination and xenophobia and related intolerance address the barriers to these factors (qtd. on 118)

[For those of you that may still remember the conference, it had to overcome much politicking by various states – some of the issues I remember most were that related to whether Zionism and casteism should be considered racism. The US had purposely sent low-level officials to the conference and later they walked out of the conference, to the disgust of most countries in the world. Four days later 9/11 occurred. There is discussion today whether the US should attend Durban II in 2009]

One of the last paragraph’s of the chapter is particularly worth extensive rumination

While greater engagement in public life has professionalized Sikh political activity, it has singularly failed to produce an effective and legitimate articulation of the Sikh political interest in British politics. Even today such an articulation remains grounded in the mode of single-issue mobilization because the structures of British elections necessitate plural coalition building and, given that Sikhs nowhere command more than 10 per cent of the total population in any local authority, the current emphasis by organizations like the Sikh Federation (UK) on community seems destined to repeat the historic failures of the IWAs to build organizations of class. (124).

So another question: For many of the most prominent political activists in our community, the state of a permanent mobilization on homeland politics is still the forefront of their vision. How does this coincide and conflict with newer generations of Sikh born in the diaspora?

Chapter 6 delves into the politics of multiculturalism. [Jodha has expressed some of his own views on this previously].

The authors open with the note that Sikhs seem to occupy a distinct position on the discussion of multiculturalism in the UK [probably in Canada as well]. In fact some critics of multiculturalism target the Sikh case in particular as they have become the paradigmatic case of a special-interest group that can always successfully negotiate an opt-out from the general rule.

Tracing certain common evolution of Sikh communities, the authors note, early immigrants tend to avoid overt differences from the general society and will choose to abandon their pagris. Some will wear them for ceremonial reasons or on Sunday visits to the Gurdwaras. However as the community grows, the self-confidence of keshadhari Sikhs will assert itself and this leads to the Sikh migrants’ conflict with the host society or government on the right to wear a turban. GSS Sagar and Tarsem Singh Sandhu were the path-breakers in 1960s Britain, while the historic Mandla v. Dowell Lee (1983) has had a major role in defining Sikhs’ relationship as a community with the British state.

While Sikhs have had much success in Britain in having their religious duties accommodated, Sikhs often exaggerate their successes and forget their many legal defeats as well. The authors end the chapter discussing the problematics of multiculturalism, specifically looking at the case of the play Behzti and its eventual cancellation. In an amusing ending, the authors reflect how much the Sikhs have learned the politics of Britain – drawing on the Anglo-Sikh heritage, engaging national and transnational lobbying (although in this article in the French case, they can work against one another as well), and most recently in the case of the Behzti affair, Sikhs can “resort to that most ancient of British traditions – the riot.”

——————————-

For Previous Discussions, see

In response to your question 2: I would like some answers regarding this issue. In this book, Singh and Tatla consider the importance of Khalistan has been reduced to a "trickle" in recent years. Can anyone confirm or elaborate? I would suggest there is still an idea for a seperate Sikh state amongst British born Sikhs, though the saliancy has never been tested. I would also like to question the use of the owrd diaspora for the Sikhs. The use of this word has been extended in recent years to include almost any group. Tatla in an earlier publication goes to some length to classify the Sikhs as a diapora. However, in Singh and Tatla he appears to contradict his own view by stating the number of Sikh pensioners living in the Punjab after a lifetime of working in the UK and by demonstrating Sikh migration has been over-whelmingly by choice, whilst keeping in with Ravenstein's classic theory regarding migration.

In response to your question 2: I would like some answers regarding this issue. In this book, Singh and Tatla consider the importance of Khalistan has been reduced to a “trickle” in recent years. Can anyone confirm or elaborate? I would suggest there is still an idea for a seperate Sikh state amongst British born Sikhs, though the saliancy has never been tested. I would also like to question the use of the owrd diaspora for the Sikhs. The use of this word has been extended in recent years to include almost any group. Tatla in an earlier publication goes to some length to classify the Sikhs as a diapora. However, in Singh and Tatla he appears to contradict his own view by stating the number of Sikh pensioners living in the Punjab after a lifetime of working in the UK and by demonstrating Sikh migration has been over-whelmingly by choice, whilst keeping in with Ravenstein’s classic theory regarding migration.

Is there an easier way to access the bookclub discussions? I didn't see that the discussion was posted.

Is there an easier way to access the bookclub discussions? I didn’t see that the discussion was posted.

Saihaj, what are you suggesting? I don't understand your comment. Updates are up every Monday for this book.

RT, I am not sure how to address your question. I would agree that large sections of Sikhs overseas do support a nation-state project. In terms of a survey, I am not sure if anything has ever been done in that direction – all we have is circumstantial evidence – from the 2001 census, UK-born Sikhs are less likely to identify themselves as Sikhs than their Indian-born parents/peers. However, I believe another study on the pluralism project at Harvard, showed that some US Sikhs most strongly identify as 'Sikhs' than any other identity. Now whether such identification as a 'Sikh' translates into support or opposition to a nation-state, well that is anyone's guess.

Now your question with regard to the applicability of the term 'diaspora' is especially interesting. I have to admit I was unfamiliar with Ravenstein's Laws and only saw this quick synopsis that I am sure doesn't do it justice. While it seems terms such as absorption and dispersion may have made more sense in 1885, I think they are unable to discuss migration in the globalized world we live in.

Now the term 'diaspora' comes from a specific Jewish understanding of an alleged dispersal from a believed homeland, although you are right that it has been expanded and sometimes used without appropriate definitions.

As I understand the term, it refers to a group sharing common traditions (that believe themselves a coherent group) and that their connections with each one another, even at different global nodes, links them stronger than to their host community. So long as a Sikh in the UK believes he/she has more in common than a Sikh in the US (or Canada or Punjab or wherever) than a gora in UK, than that Sikh still constitutes part of the diaspora. Our marriage patterns really reflect this.

Well would love to hear more of your thoughts.

Saihaj, what are you suggesting? I don’t understand your comment. Updates are up every Monday for this book.

RT, I am not sure how to address your question. I would agree that large sections of Sikhs overseas do support a nation-state project. In terms of a survey, I am not sure if anything has ever been done in that direction – all we have is circumstantial evidence – from the 2001 census, UK-born Sikhs are less likely to identify themselves as Sikhs than their Indian-born parents/peers. However, I believe another study on the pluralism project at Harvard, showed that some US Sikhs most strongly identify as ‘Sikhs’ than any other identity. Now whether such identification as a ‘Sikh’ translates into support or opposition to a nation-state, well that is anyone’s guess.

Now your question with regard to the applicability of the term ‘diaspora’ is especially interesting. I have to admit I was unfamiliar with Ravenstein’s Laws and only saw this quick synopsis that I am sure doesn’t do it justice. While it seems terms such as absorption and dispersion may have made more sense in 1885, I think they are unable to discuss migration in the globalized world we live in.

Now the term ‘diaspora’ comes from a specific Jewish understanding of an alleged dispersal from a believed homeland, although you are right that it has been expanded and sometimes used without appropriate definitions.

As I understand the term, it refers to a group sharing common traditions (that believe themselves a coherent group) and that their connections with each one another, even at different global nodes, links them stronger than to their host community. So long as a Sikh in the UK believes he/she has more in common than a Sikh in the US (or Canada or Punjab or wherever) than a gora in UK, than that Sikh still constitutes part of the diaspora. Our marriage patterns really reflect this.

Well would love to hear more of your thoughts.

About the question:

I would argue many are leaving the Gurdwara (at least here in the US) although this may have most to do with relationship with the state, efficiency, and laws than any 'natural impulse.' The examples of SRI (Sikh Research Institute), ENSAAF, Sikh Coalition, SALDEF, Jago, Seattle Sikh Retreat, the Jakara Movement, and Surat (to name but a few) seem to attest to this.

About the question:

I would argue many are leaving the Gurdwara (at least here in the US) although this may have most to do with relationship with the state, efficiency, and laws than any ‘natural impulse.’ The examples of SRI (Sikh Research Institute), ENSAAF, Sikh Coalition, SALDEF, Jago, Seattle Sikh Retreat, the Jakara Movement, and Surat (to name but a few) seem to attest to this.

Mewa Singh, my comment was supposed to be helpful, it's a shame you took it the wrong way. The bookclub discussions get lost and embedded with all the other TLH posts. So even if it is posted on Monday and I don't get the check the blog until midweek then I have to scroll through all the other posts and sometimes I don't get to the bookclub posts. So maybe if a section of the site was dedicated to the bookclub because it really is a unique initiative and deserves a special focus.

Mewa Singh, my comment was supposed to be helpful, it’s a shame you took it the wrong way. The bookclub discussions get lost and embedded with all the other TLH posts. So even if it is posted on Monday and I don’t get the check the blog until midweek then I have to scroll through all the other posts and sometimes I don’t get to the bookclub posts. So maybe if a section of the site was dedicated to the bookclub because it really is a unique initiative and deserves a special focus.

Mewa Singh –

Ravenstein's LAws (essentially push-pull) were created to explain internal migration in the UK during the 19th century. It was found they were also applicable to the mass global movements during the same period. Whilst new theories of migration occur on a regular basis they can all be reduced to Ravenstein's push-pull. Only the context has changed.

Census 2001 is the most thorough examination of Sikhs, or any other religious group fo that matter, ever to be executed in the UK. Samples are useful, but are prone to error. I can confirm in the UK no such survey has ever taken place. However, the survey would depend on the questions asked, and the geography of the survey.

Historically, the term diaspora has been the preserve of a victim group. In Singh and Tatla's text they go to some length to ensure the reader does not come to that conclusion rgarding Sikhs. Your definition also sounds very similar to ideas of what constitutes an ethnic group. I would therefore be wary of the using the term diaspora for Sikhs. A diaspora means a very low possibility, if any at all, of return. Most Sikhs can return and many have/do. Singh and Tatla also state Sikhs were never indebted labour and they moved through choice. Sure, your definition can help explain something, but I would suggest, possibily due to the work of R. Cohen (who Tatla leans on a great deal) the term diaspora has been diluted by the term ethnicity.

Keep up the good work, enjoying the discussion.

Mewa Singh –

Ravenstein’s LAws (essentially push-pull) were created to explain internal migration in the UK during the 19th century. It was found they were also applicable to the mass global movements during the same period. Whilst new theories of migration occur on a regular basis they can all be reduced to Ravenstein’s push-pull. Only the context has changed.

Census 2001 is the most thorough examination of Sikhs, or any other religious group fo that matter, ever to be executed in the UK. Samples are useful, but are prone to error. I can confirm in the UK no such survey has ever taken place. However, the survey would depend on the questions asked, and the geography of the survey.

Historically, the term diaspora has been the preserve of a victim group. In Singh and Tatla’s text they go to some length to ensure the reader does not come to that conclusion rgarding Sikhs. Your definition also sounds very similar to ideas of what constitutes an ethnic group. I would therefore be wary of the using the term diaspora for Sikhs. A diaspora means a very low possibility, if any at all, of return. Most Sikhs can return and many have/do. Singh and Tatla also state Sikhs were never indebted labour and they moved through choice. Sure, your definition can help explain something, but I would suggest, possibily due to the work of R. Cohen (who Tatla leans on a great deal) the term diaspora has been diluted by the term ethnicity.

Keep up the good work, enjoying the discussion.

Saihaj – I didn't take it wrongly at all – for the time being, you can just go to the drop down menu on the right, click on 'book club' and you can keep uptodate with our progress.

RT – I understand what you are saying about Ravenstein, but do you really believe that everything can be explained by push/pull? I see use for the theory, but it just seems far too simplistic.

You are right about the historicity of the term 'diaspora', but it isn't even just a victim group – specifically it is the Jews. However, I think <a href="http://books.google.com/books?id=R4IiYFhliv4C&pg=PA198&lpg=PA198&dq=philip+curtin+diaspora+armenian&source=web&ots=mmkDlZ_R9q&sig=2jAepqe5Ub4kywlG7DkbuFdYXJo&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPP1,M1" rel="nofollow">Philip Curtin really opened up the term in relationship to early modern 'trade diasporas.' I think you may be right in terms of overlap of 'diaspora' and 'ethnic group' but I am not sure how you are suggesting to disentangle the two terms? Also I am not sure how you are defining 'diaspora'? What terms would you use in its place?

For instance you mention that there must be a small likelihood of return for the term to be apt – however in the most described examples Jews and Armenians – both have opportunities to return whether to Israel or Armenia. Many Jews and Armenians return or atleast have the option of returning. If we use the 'low' possibility of return in the modern context, where structural prohibitions are in place, it seems to me then only Palestinians and possibly some African groups would constitute 'true' diasporic populations according to this definition?

I still have to read more on the R. Cohen you suggested. Are there any specific books or articles, you would recommend?

Looking forward to your comments (and maybe others')

Saihaj – I didn’t take it wrongly at all – for the time being, you can just go to the drop down menu on the right, click on ‘book club’ and you can keep uptodate with our progress.

RT – I understand what you are saying about Ravenstein, but do you really believe that everything can be explained by push/pull? I see use for the theory, but it just seems far too simplistic.

You are right about the historicity of the term ‘diaspora’, but it isn’t even just a victim group – specifically it is the Jews. However, I think Philip Curtin really opened up the term in relationship to early modern ‘trade diasporas.’ I think you may be right in terms of overlap of ‘diaspora’ and ‘ethnic group’ but I am not sure how you are suggesting to disentangle the two terms? Also I am not sure how you are defining ‘diaspora’? What terms would you use in its place?

For instance you mention that there must be a small likelihood of return for the term to be apt – however in the most described examples Jews and Armenians – both have opportunities to return whether to Israel or Armenia. Many Jews and Armenians return or atleast have the option of returning. If we use the ‘low’ possibility of return in the modern context, where structural prohibitions are in place, it seems to me then only Palestinians and possibly some African groups would constitute ‘true’ diasporic populations according to this definition?

I still have to read more on the R. Cohen you suggested. Are there any specific books or articles, you would recommend?

Looking forward to your comments (and maybe others’)

RT – as soon as I wrote this I read an article that mentioned Cohen:

So now, where do the Sikhs fall? It seems from this that 'diaspora' is broad enough to envelop the Sikhs if we go beyond 'victim diaspora.'

RT – as soon as I wrote this I read an article that mentioned Cohen:

So now, where do the Sikhs fall? It seems from this that ‘diaspora’ is broad enough to envelop the Sikhs if we go beyond ‘victim diaspora.’

Mewa

Thanks for the link to Philip Curtin – hadnt seen it before. I know Ravenstein sounds simplistic, however, I still think all migration theories can be reduced to that. There is a book called something like Asians, Aliens and Strangers by Anne Kershen, some theories are discussed there. You can also check out Castles and Miller's books and their journal literature. You see migration theorists are trying to account for non-white migrants and try to suggest there are other reasons, bit IMO there are not – it is the same for white or other people.

To understand where the Sikhs are (victim or trade) – I would suggest it depends to what point in time you go back to. Most Sikhs left the Punjab after WW2 – they all had an option of return. I think when people talk about Jews and Armenians retuning – do they mean the migrants themselves or do they mean future generations.

TO return to the Sikhs – is the Punjab a Sikh land? Who overthrew them? Do we take the end of Ranjit Singh's rule as the event that led to the outward migration of Sikhs?

Mewa

Thanks for the link to Philip Curtin – hadnt seen it before. I know Ravenstein sounds simplistic, however, I still think all migration theories can be reduced to that. There is a book called something like Asians, Aliens and Strangers by Anne Kershen, some theories are discussed there. You can also check out Castles and Miller’s books and their journal literature. You see migration theorists are trying to account for non-white migrants and try to suggest there are other reasons, bit IMO there are not – it is the same for white or other people.

To understand where the Sikhs are (victim or trade) – I would suggest it depends to what point in time you go back to. Most Sikhs left the Punjab after WW2 – they all had an option of return. I think when people talk about Jews and Armenians retuning – do they mean the migrants themselves or do they mean future generations.

TO return to the Sikhs – is the Punjab a Sikh land? Who overthrew them? Do we take the end of Ranjit Singh’s rule as the event that led to the outward migration of Sikhs?

[…] The Book Club recently commented on the terminology and applicability of the term ‘diaspora’ to the Punjabi community outside Punjab-and whether ‘diaspora’ can apply to a group that won’t be returning to the homeland. For more discussion of the term, check out the Book Club. […]

[…] the story feeling unfamiliar, exotic, or far, it is re-placed to popularize it among youth in the diaspora. Whether this means it’s more risque or departs dramatically from the original, I’m […]

Sikhs need to unite.

Khalistani's dont even invite all Gurdwara's to their events, how can they get maximum support if they do let people know what they are doing?

15,000-20,000 sikhs can to 1984/Khalistan rally in june 2007, yet most were from west midlands, why weren't london sikhs offically invited?

Khalistan definitely has supprt, dont deny it, recent Gurdwara elections show support for Pro-Khalistan slates in UK, USA, CANADA plus more.

But they need to be more inclusive.

Sikhs need to unite.

Khalistani’s dont even invite all Gurdwara’s to their events, how can they get maximum support if they do let people know what they are doing?

15,000-20,000 sikhs can to 1984/Khalistan rally in june 2007, yet most were from west midlands, why weren’t london sikhs offically invited?

Khalistan definitely has supprt, dont deny it, recent Gurdwara elections show support for Pro-Khalistan slates in UK, USA, CANADA plus more.

But they need to be more inclusive.

BUCHANGI

Can you provide evidence 15 – 20, 000 Sikhs attended this rally. Figure represents around 4.5 to 6 percent of the Sikh population in England. Is this a high figure? I think the BNP got about 4.5 percent of votes in the recent London Assembly elections winning them one seat. Does having this much support warrant the idea Khalistan is wanted by all Sikhs?

BUCHANGI

Can you provide evidence 15 – 20, 000 Sikhs attended this rally. Figure represents around 4.5 to 6 percent of the Sikh population in England. Is this a high figure? I think the BNP got about 4.5 percent of votes in the recent London Assembly elections winning them one seat. Does having this much support warrant the idea Khalistan is wanted by all Sikhs?

http://worldsikhnews.com/11%20June%202008/Photo%2…

Pic's 3-9 were done from my mobile, sorry i couldnt get better shots.

Above is a link to http://WWW.WORLDSIKHNEWS.COM – a US based Online newspublishing site.

It shows pictures of Sikhs remembering and protesting about 1984.

According to my calculations – 750,000 sikhs in UK.

SO IF 20,000 DID COME ITS ONLY 2.7%

What i mean to say is that 100,000 – 250,000 sikhs can come to events like this in UK, USA AND CANADA, plus smaller numbers in other countries. This way, we may hit 1 million.

But we lack to co-ordination and co-operation, to hold such large gatherings around the world, on the same day.

We must also remember that many people are to old or young to actively participate, so the potential number should be less than 750,000. (though may prams and elderly people were there too.)

http://worldsikhnews.com/11%20June%202008/Photo%20Gallery%201.htm

Pic’s 3-9 were done from my mobile, sorry i couldnt get better shots.

Above is a link to http://WWW.WORLDSIKHNEWS.COM – a US based Online newspublishing site.

It shows pictures of Sikhs remembering and protesting about 1984.

According to my calculations – 750,000 sikhs in UK.

SO IF 20,000 DID COME ITS ONLY 2.7%

What i mean to say is that 100,000 – 250,000 sikhs can come to events like this in UK, USA AND CANADA, plus smaller numbers in other countries. This way, we may hit 1 million.

But we lack to co-ordination and co-operation, to hold such large gatherings around the world, on the same day.

We must also remember that many people are to old or young to actively participate, so the potential number should be less than 750,000. (though may prams and elderly people were there too.)

BUCHANGI

I am not writing this to convey any opposition to Khalistan or support for it. However, I frequently point to the troubled and failed states of Pakistan and Afghanistan as potenial future outcomes if any split from India emerges.

I would ask you from where you obtained a figure of 750, 000 Sikhs in the UK. There is 327, 343 in England and 336, 179 in the UK. These are 2001 Census figures. They cannot be disputed and as Singh and Tatla point out in their book the UK foremost important statistician regarding ethnicity and religion has proved beyond doubt these figures are highly accurate. Singh and tatla also guess there are 50, 000 illegal Sikh immigrants in the UK. I have no reason to dispute their claim, but they hhave no way to verify this.

When did 100, 000 to 250, 000 Sikhs attend such a meeting in the UK? even if 1 million Sikhs did cordinate a global meeting it will only represent 5% of the global popuation. Id this enough? Does it repressent the majority? Do the other 95% oppose Khalistan? Perhaps they do not care enough?

Where

BUCHANGI

I am not writing this to convey any opposition to Khalistan or support for it. However, I frequently point to the troubled and failed states of Pakistan and Afghanistan as potenial future outcomes if any split from India emerges.

I would ask you from where you obtained a figure of 750, 000 Sikhs in the UK. There is 327, 343 in England and 336, 179 in the UK. These are 2001 Census figures. They cannot be disputed and as Singh and Tatla point out in their book the UK foremost important statistician regarding ethnicity and religion has proved beyond doubt these figures are highly accurate. Singh and tatla also guess there are 50, 000 illegal Sikh immigrants in the UK. I have no reason to dispute their claim, but they hhave no way to verify this.

When did 100, 000 to 250, 000 Sikhs attend such a meeting in the UK? even if 1 million Sikhs did cordinate a global meeting it will only represent 5% of the global popuation. Id this enough? Does it repressent the majority? Do the other 95% oppose Khalistan? Perhaps they do not care enough?

Where

RT

The most commonly used figure for 2007/08 is 750,000 in various official letters and communicates from British politicians.

If you re-red my above comment, i have suggested the potential to gather such large numbers of Sikhs, in UK and around the world.

Sikh around the world know that status quo is insufficient, but directionless khalistani leaders discourage people from following them.

Silence doesn't mean that people are against something.

As for Punjab, People know that they will be harassed if they openly speak of Khalistan so they are quite, but more than enough examples are available to shows Sikhs in India supports Khalistan in large numbers.

RT

The most commonly used figure for 2007/08 is 750,000 in various official letters and communicates from British politicians.

If you re-red my above comment, i have suggested the potential to gather such large numbers of Sikhs, in UK and around the world.

Sikh around the world know that status quo is insufficient, but directionless khalistani leaders discourage people from following them.

Silence doesn’t mean that people are against something.

As for Punjab, People know that they will be harassed if they openly speak of Khalistan so they are quite, but more than enough examples are available to shows Sikhs in India supports Khalistan in large numbers.

BUCHANGI

Can you provide any of these official sources that claim there 750k SIkhs in the UK. I work every day with the Census and am amazed at the stuff people come out with. Please provide at least a link to 1 British politician that has claimed this amount.

I am afraid unless there is a democratic vote we cannot say whether Sikhs support India. Can I ask you also – what is wring with Sikhs being Indian. Also, would do you think Sikhs will achieve with their own country being they have not acheived anything much to date. By the way , I am also a Sikh.

BUCHANGI

Can you provide any of these official sources that claim there 750k SIkhs in the UK. I work every day with the Census and am amazed at the stuff people come out with. Please provide at least a link to 1 British politician that has claimed this amount.

I am afraid unless there is a democratic vote we cannot say whether Sikhs support India. Can I ask you also – what is wring with Sikhs being Indian. Also, would do you think Sikhs will achieve with their own country being they have not acheived anything much to date. By the way , I am also a Sikh.

Sorry, i couldn't find any online sources, but i have seen many prints howing sure number. 9somethign i can't prove.).

Yes, sikhs should have a vote on Khalistan, monitored but UN FORCES, as people in India will be scared of Indian govt threats.

Sikhs loved India, but after so much discrimination, insulting, unfairness, countless examples. (you would know most.)

Delhi genocide – across india

Asian games- on sikhs allowing in delhi, including NRI'S and Congress MP'S.

Water rights

Not recognising sikhs are seperate.

gurdwara act

anand karag act

2% quota of army

250,000 innocent killed by indian govt.

AND MORE – MUCH MORE

After all this, how can we be happy to be indian. I know some people say they are, but when you talk to them the truth comes out.

My mum always says that "punjab has no industry so what will we earn"

well indian govt denies punjab a fair chance to attarct investment.

Most industry in punjab i sfrom punjabi's.

Khalistan govt would have a much better investment policy to attract trade. – Ofcourse everything i snot garunteed, but we have more scope in free Khalistan than status quo.

http://www.sikhfreedom.com – is a good site.- Read the KHALISTAN LAB, lots of info in POST – INDEPENDENCE.

Sorry, i couldn’t find any online sources, but i have seen many prints howing sure number. 9somethign i can’t prove.).

Yes, sikhs should have a vote on Khalistan, monitored but UN FORCES, as people in India will be scared of Indian govt threats.

Sikhs loved India, but after so much discrimination, insulting, unfairness, countless examples. (you would know most.)

Delhi genocide – across india

Asian games- on sikhs allowing in delhi, including NRI’S and Congress MP’S.

Water rights

Not recognising sikhs are seperate.

gurdwara act

anand karag act

2% quota of army

250,000 innocent killed by indian govt.

AND MORE – MUCH MORE

After all this, how can we be happy to be indian. I know some people say they are, but when you talk to them the truth comes out.

My mum always says that “punjab has no industry so what will we earn”

well indian govt denies punjab a fair chance to attarct investment.

Most industry in punjab i sfrom punjabi’s.

Khalistan govt would have a much better investment policy to attract trade. – Ofcourse everything i snot garunteed, but we have more scope in free Khalistan than status quo.

http://www.sikhfreedom.com – is a good site.- Read the KHALISTAN LAB, lots of info in POST – INDEPENDENCE.

BUCHANGI

The census figures are correect – there is never 750k Sikhs in the Uk. Further, the popualation will decrease not increase and i can prove it.

There maybe more scope for improvemnt in Khalistan, but I would imagine Pakistan would invade pretty quiick. Not sure why you think the UN will give Sikhs any joy – who runs the UN? Sikhs have no state of their own due to their past. Remember, no-one owes you anmything. If they have failed to create a state in the past – you should question why? The blame I would imagine is die to a lack of social capital.

BUCHANGI

The census figures are correect – there is never 750k Sikhs in the Uk. Further, the popualation will decrease not increase and i can prove it.

There maybe more scope for improvemnt in Khalistan, but I would imagine Pakistan would invade pretty quiick. Not sure why you think the UN will give Sikhs any joy – who runs the UN? Sikhs have no state of their own due to their past. Remember, no-one owes you anmything. If they have failed to create a state in the past – you should question why? The blame I would imagine is die to a lack of social capital.

Sikhs lack local co-ordination linking to a national and international network.

This will be developed a the coming years.

Foriegn based sikhs will have to unite their strength.

Sikhs lack local co-ordination linking to a national and international network.

This will be developed a the coming years.

Foriegn based sikhs will have to unite their strength.

RT – Sorry for the delay in response. I will look at the books you recommended, the Kershen one especially sounds interesting.

With regards to Armenians and Jews, they mean that the immigrants themselves can return. The Western Armenians (meaning those that were in the lands that were forced to flee after the genocide during WWI by the Ottomans) may not have been able to return to their homeland per se, but there was an option of going to the Eastern Armenians lands that would become incorporated into the USSR. Interesting, because while writing this, could we then make the same case for Sikhs from Western Punjab?

I think again there is slippage in the terminology, because for the most part diaspora is just used for any immigrant community no matter what the reason for their movement. Until 'integration' occurs and their bonds with other community members (like in marriage patterns I earlier discussed) is decreased and they are most associated with their 'host' society, I still think the term diaspora is apt.

Now on the issue between Buchangi and RT:

There is no data anyways and there will be no data in this way.

Buchangi – I agree with you that large sections of the Sikh community (whether these constitute a majority or not, who knows, but they sure are vocal!) probably do support a Sikh nation-state project. However, let us not exaggerate figures and I am more inclined to believe that of the census (give or take some) than to believe Sikh 'representatives' that have every reason to inflate figures. And I think I agree with RT that for most of the Sikh population, this is no longer high on their agenda. However, as Gurharpal and Darshan Tatla write, another "critical" event like 1984 can change everything (you can see the quick mass mobilization after the Dehra Sacha Sauda incident as an example).

RT – no census on the popularity of a Sikh nation-state can ever occur. So we will never really know. I have a feeling in 1984-1990 it would have been the majority. In the diaspora you would probably even had almost unanimity. Still non-states do not have the power to take these sort of measures, censuses are only conducted by states. There are a plethora of reasons why Sikhs do not have a state – some reasons far more important than lack of social capital. The most important is that the Indian state can impose its hegemony using military force at anytime (which they have). Gurharpal Singh's Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab is an essential read in this aspect. He writes that without an external impetus, the chance of Sikh success is virtually nil.

RT – Sorry for the delay in response. I will look at the books you recommended, the Kershen one especially sounds interesting.

With regards to Armenians and Jews, they mean that the immigrants themselves can return. The Western Armenians (meaning those that were in the lands that were forced to flee after the genocide during WWI by the Ottomans) may not have been able to return to their homeland per se, but there was an option of going to the Eastern Armenians lands that would become incorporated into the USSR. Interesting, because while writing this, could we then make the same case for Sikhs from Western Punjab?

I think again there is slippage in the terminology, because for the most part diaspora is just used for any immigrant community no matter what the reason for their movement. Until ‘integration’ occurs and their bonds with other community members (like in marriage patterns I earlier discussed) is decreased and they are most associated with their ‘host’ society, I still think the term diaspora is apt.

Now on the issue between Buchangi and RT:

There is no data anyways and there will be no data in this way.

Buchangi – I agree with you that large sections of the Sikh community (whether these constitute a majority or not, who knows, but they sure are vocal!) probably do support a Sikh nation-state project. However, let us not exaggerate figures and I am more inclined to believe that of the census (give or take some) than to believe Sikh ‘representatives’ that have every reason to inflate figures. And I think I agree with RT that for most of the Sikh population, this is no longer high on their agenda. However, as Gurharpal and Darshan Tatla write, another “critical” event like 1984 can change everything (you can see the quick mass mobilization after the Dehra Sacha Sauda incident as an example).

RT – no census on the popularity of a Sikh nation-state can ever occur. So we will never really know. I have a feeling in 1984-1990 it would have been the majority. In the diaspora you would probably even had almost unanimity. Still non-states do not have the power to take these sort of measures, censuses are only conducted by states. There are a plethora of reasons why Sikhs do not have a state – some reasons far more important than lack of social capital. The most important is that the Indian state can impose its hegemony using military force at anytime (which they have). Gurharpal Singh’s Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab is an essential read in this aspect. He writes that without an external impetus, the chance of Sikh success is virtually nil.

Mewa Singh

You have a fair point about whether diaspora is the correct term when using western punjab as an example. However, only Ranjit Singh has ruled this area under any political banner than could be conflated with Sikhism. History also tells us Sikhs were in the minority within that Kingdom – so I think tht complicates things a tad.

So, when did Sikhs create a nation-state? Further, perhaps you could list some of the reasons why have yet to see a Sikhs nation-state. I think the lack of social capital has been crucial. There is a paper by Robert Putnam from 1993 in which he sets the basis for the creation of cohesion – that leads to a state – this was before his classic 2000 book. Sikhs have a society based on family and honour and that has virtually destroyed not just Sikhs but Punjabis.

Also, it is still to early to tell whether marrigae patterns will remain the same. At the moment in the UK we are really only now seeing 3rd generations who are ready to get married – from a research point of view – I have seen research from Muslims in the same generation and the consesus is to marry UK born citizens. From a personal point of view – I see many more Sikhs now with non-Sikh partners, though I cant prove this point. The next census is out in 2013 and will make the most interesting reading.

Mewa Singh

You have a fair point about whether diaspora is the correct term when using western punjab as an example. However, only Ranjit Singh has ruled this area under any political banner than could be conflated with Sikhism. History also tells us Sikhs were in the minority within that Kingdom – so I think tht complicates things a tad.

So, when did Sikhs create a nation-state? Further, perhaps you could list some of the reasons why have yet to see a Sikhs nation-state. I think the lack of social capital has been crucial. There is a paper by Robert Putnam from 1993 in which he sets the basis for the creation of cohesion – that leads to a state – this was before his classic 2000 book. Sikhs have a society based on family and honour and that has virtually destroyed not just Sikhs but Punjabis.

Also, it is still to early to tell whether marrigae patterns will remain the same. At the moment in the UK we are really only now seeing 3rd generations who are ready to get married – from a research point of view – I have seen research from Muslims in the same generation and the consesus is to marry UK born citizens. From a personal point of view – I see many more Sikhs now with non-Sikh partners, though I cant prove this point. The next census is out in 2013 and will make the most interesting reading.

RT,

Sorry for the delayed response.

About your first point, must a community be the majority to be be labeled a diaspora? I don't think that this would really apply at all.

As far as Sikhs creating a nation-state, of course Sikhs have not had one in the pasat – the nation-state is a recent construct and where else in Asia do you have them prior to the 20th century?

As far as a list of reasons, Gurharpal Singh lists a number for the failure of the Khalistani movement in his Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab. The most important is that the Indian state can assert its hegemony through sheer force and did so. Thus despite the claims of police chief KPS Gill, Gurharpal Singh argues that ultimately it was the army that ‘broke the militants’ backs’ and not the Punjab Police, although they often took credit for the army’s actions. The anti-terrorist policy of SS Ray and Julio Ribiero differed only in degree with that of Gill, but not in kind. Ultimately through massive actions such as Operation Rakshak II, involving over 250,000 army and police personnel, was the Indian State able to gain the upper hand (166).

Sheer force dominance is ultimately the reason for the Khalistani failure.

As far as social capital goes, I have read Putnam's book Bowling Alone. I think there may be a point in terms of civil society and greater Sikh-Sikh linkages, still the issue of cohesiveness is addressed by Gurharpal Singh.

Gurharpal Singh notes that the quintessential features of modern Punjabi Sikh identity have remained largely unaltered since the 1930s. These include the declining proportions of the sahajdhari Sikhs and the predominant position of the Jats politically and numerically within the Sikhs (87). Singh thus notes that the modern Sikh identity is remarkably cohesive. Despite this cohesiveness, theories regarding post-Nehruvian centralization and the economic effects after the Green Revolution dominate discourse of the events leading to the rise of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, neglecting the forces from within the community.

Finally with regards to marriage patterns. You are right, who can predict. In addition, we should have the numbers of those Sikhs that are marrying Sikhs from Punjab and other countries as well to be able to look at the issue comparatively.

If it isn't yet obviously, I HIGHLY recommend you to look at Gurharpal Singh's Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab for a more nuanced discussion of the issue of the Sikh nationalist attempt.

RT,

Sorry for the delayed response.

About your first point, must a community be the majority to be be labeled a diaspora? I don’t think that this would really apply at all.

As far as Sikhs creating a nation-state, of course Sikhs have not had one in the pasat – the nation-state is a recent construct and where else in Asia do you have them prior to the 20th century?

As far as a list of reasons, Gurharpal Singh lists a number for the failure of the Khalistani movement in his Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab. The most important is that the Indian state can assert its hegemony through sheer force and did so. Thus despite the claims of police chief KPS Gill, Gurharpal Singh argues that ultimately it was the army that ‘broke the militants’ backs’ and not the Punjab Police, although they often took credit for the army’s actions. The anti-terrorist policy of SS Ray and Julio Ribiero differed only in degree with that of Gill, but not in kind. Ultimately through massive actions such as Operation Rakshak II, involving over 250,000 army and police personnel, was the Indian State able to gain the upper hand (166).

Sheer force dominance is ultimately the reason for the Khalistani failure.

As far as social capital goes, I have read Putnam’s book Bowling Alone. I think there may be a point in terms of civil society and greater Sikh-Sikh linkages, still the issue of cohesiveness is addressed by Gurharpal Singh.

Gurharpal Singh notes that the quintessential features of modern Punjabi Sikh identity have remained largely unaltered since the 1930s. These include the declining proportions of the sahajdhari Sikhs and the predominant position of the Jats politically and numerically within the Sikhs (87). Singh thus notes that the modern Sikh identity is remarkably cohesive. Despite this cohesiveness, theories regarding post-Nehruvian centralization and the economic effects after the Green Revolution dominate discourse of the events leading to the rise of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, neglecting the forces from within the community.

Finally with regards to marriage patterns. You are right, who can predict. In addition, we should have the numbers of those Sikhs that are marrying Sikhs from Punjab and other countries as well to be able to look at the issue comparatively.

If it isn’t yet obviously, I HIGHLY recommend you to look at Gurharpal Singh’s Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab for a more nuanced discussion of the issue of the Sikh nationalist attempt.

According to the True Spirit Of Sikhism we must have tolerance for people of all religions . So why should we think that we need a separate state ? None of our Gurus demanded separate state . Do you think with their Divine powers it was impossible for them to create one for their Sikhs ? Instaed they wanted their sikhs to remain among other people and be an example for them .

General Books ON Principles and Ethics of Sikhism

According to the True Spirit Of Sikhism we must have tolerance for people of all religions . So why should we think that we need a separate state ? None of our Gurus demanded separate state . Do you think with their Divine powers it was impossible for them to create one for their Sikhs ? Instaed they wanted their sikhs to remain among other people and be an example for them .

General Books ON Principles and Ethics of Sikhism

I think it is so painful that our dharam is caught up in this Khalistan nonsense. Satnam above me is correct, since when do sikhs have any alligenece to land? Justice and prosperity should be faught for, but for all these kids in britain and other places who focus on this egotistical childish fight, they are taking everyday away from enlightenment and seva.

I think it is about time we get our objectives in order. What is more important to us? The slow demise of the youth of our religion, or some hypothetical land?

I think it is so painful that our dharam is caught up in this Khalistan nonsense. Satnam above me is correct, since when do sikhs have any alligenece to land? Justice and prosperity should be faught for, but for all these kids in britain and other places who focus on this egotistical childish fight, they are taking everyday away from enlightenment and seva.

I think it is about time we get our objectives in order. What is more important to us? The slow demise of the youth of our religion, or some hypothetical land?

Great beawt ! Iwish to apprentice whilst you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a weblog

website? The account helped me a applicable deal.

I had been tiny bit familiar oof this your broadcast offered shiny clear idea