The question is poignant: What makes anyone want to blow themselves up for a cause?

As the discussion of violence has manifested itself a number of times on this young blog, I read with interest discussions of this documentary, My Daughter the Terrorist. As most discussions on political violence are the tales of men or women-victims, often using the language of chest-beating and revenge or human rights and dignity, this documentary seems to focus on a different tale. From its own webpage it states:

In this intimate and personal portrait we join two young female elite soldiers trained for the ultimate mission. We share their childhood experiences, their dreams and their families’ loss. Left behind are the mothers. [Emphasis added]

As we celebrate the New Year and look forward to what it holds in store for us (at the very least an election!), it is important to look back and remember what we have experienced as a community this past year. In celebration of the Sikh Diaspora and what it represents to us today, here is a look back at some of the global stories, books, films and websites that impacted our community in 2007.

As we celebrate the New Year and look forward to what it holds in store for us (at the very least an election!), it is important to look back and remember what we have experienced as a community this past year. In celebration of the Sikh Diaspora and what it represents to us today, here is a look back at some of the global stories, books, films and websites that impacted our community in 2007.

- Young Sikh Men Get Haircuts, Annoying Their Elders. “It’s usually college-going students who are more worried about looking good than about their spiritual identity…[It] releases a certain amount of pressure.”

- A new website, Sikh Chic, discussing articles related to the art and culture of the Sikh Diaspora was launched. “We need to re-think the Sikh idea in the North American idiom, in our language, in our way of articulating our thoughts.”

- The Sikh clergy issues an edict directing the Sikh Sangat to snap all ties, including social, religious and political, with Baba Ram Rahim Gurmit, head, Dera Sacha Sauda, and its followers.

- Several books for and about Sikhs are published and discussed including Shame, Sacred Games, Sikhs in Britain, Londonstani, Sikhs Unlimited, I See No Stranger: Early Sikh Art and Devotion.

- A Sikh-Canadian group slams the long-standing immigration policy that forces people with the surname Singh or Kaur to change their last names. It was later noted that the immigration letter sent out was poorly worded.

Blimey. Last week National Public Radio picked up a story about one of the newest scams to hit the community, that of Runaway Grooms. If NPR is doing a story about Punjabis and/or Sikhs, you’d hope it would be for something like this instead. So forgive me, if I think it’s disappointing (although maybe not surprising) that instead our community is the focus of an issue that seems to be quite prevalent in the Punjabi community in India and has links to England and North America aswell. Actually, it is very prevalent. Data suggests that 15,000 women in Punjab alone have been victim to men who, after getting married (and after taking the dowry money) return abroad never to be heard from again. Yup, these guys pull a Houdini. Here’s an excerpt from the NPR piece:

Blimey. Last week National Public Radio picked up a story about one of the newest scams to hit the community, that of Runaway Grooms. If NPR is doing a story about Punjabis and/or Sikhs, you’d hope it would be for something like this instead. So forgive me, if I think it’s disappointing (although maybe not surprising) that instead our community is the focus of an issue that seems to be quite prevalent in the Punjabi community in India and has links to England and North America aswell. Actually, it is very prevalent. Data suggests that 15,000 women in Punjab alone have been victim to men who, after getting married (and after taking the dowry money) return abroad never to be heard from again. Yup, these guys pull a Houdini. Here’s an excerpt from the NPR piece:

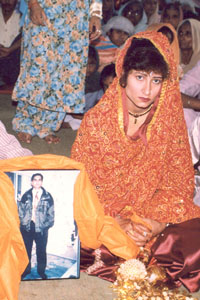

Satwant Kaur was full of hope and happiness on the day she got married. She had landed a husband who lived and worked overseas in Italy before returning to India to find a bride. She was looking forward to leaving her home in Punjab, northern India, for an exciting new life in Europe. Less than a week after the wedding, it became obvious that her husband, Sarwan Singh, had no intention of taking her with him back to Italy. She was the victim of a scam.

Women in India pay these men a hefty dowry in anticipation of the marriage and the promise to travel with them abroad. However, as it’s becoming increasingly clear, these men have NO intention of bringing their brides overseas and instead extort them of, what often is, their family’s savings. NPR may have picked this story up just recently, but this tale is not new. Ali Kazimi, a filmmaker, made a documentary about this called Runaway Grooms which has screened at various film festivals across the country. It’s a powerful film that leaves you in disbelief that this continues to happen in our community. What impacted me most about this film, however, was the strength that existed within these women who had quite clearly been abandoned. It reminded me of the same strength I see from Punjabi and Sikh women, that I know, who have come through similar tribulations.

At the root of this problem, and many others, is the tradition of daaj or dowry. Is this going away or has it’s form simply changed? I would suggest listening to the NPR piece and watching Runaway Grooms and then thinking about the impact this is having on our community. Our religion does not condone injustice, but more often than not, when those in our community are victims of fraud and lies, we always seem to look the other way…

“Indians, many of whom were Sikh, worked at the Hammond Mill before its demise in 1922. During that time period, the Indians left their mark on Astoria, participating in wrestling matches, occupying Alderbrook also known as “Hindu Alley,” and forming the Ghadar political party. Courtesy of Clatsop County Historical Society.” (source: The Daily Astorian)

One of the legacies of the earliest Sikh and Indian immigrants to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century was the creation of the Ghadar Party, a political movement based in northern California that sought to promote India’s liberation from British rule.

Led by Indian expatriates in the United States, the Ghadar Party was formed in 1913. One of its main activities was the publishing of literature to promote resistance to British rule and for a free India. Obviously a threat to the ruling class, the literature was banned in India, and upon their capture, the Ghadarites were often imprisoned or executed as terrorists by the British.

This year, the San Francisco headquarters of the Ghadar Party has been opened to the public by the Indian Consulate as a museum. The printing press that the Ghadar Party used to print their literature is also now on display at the Gurdwara in Stockton, California. However, while it was previously believed that the Ghadar Party was founded in California, historians now place the genesis of the movement further north in the state of Oregon, where Johanna Ogden recently mapped a forgotten (and primarily) Sikh settlement of laborers in 1910 known as “Hindu Alley”.

This post by our Mehmaan is none other than Harinder Singh. About Harinder Singh – he works with the Sikh Research Institute and the Panjab Digital Library to address all things Sikhi and Panjabi. http://twitter.com/1force

I have taken some time off to be Mr. Mom while my wife is on a work assignment in India. In preparing to make the move to Bangalore, I was excited about being in the land of MS Subbulakhsmi (renowned Carnatic vocalist) and Kalmane (locally grown 100% Arabica beans) coffee. Being here for about three weeks, this is what I have discovered: people are nicer than the North, infrastructure is horrible, and there is not much to see in the city. Even Frommers.com couldn’t come up a list of not-to-be-missed attractions in Bangalore, though people in India claim it to be a great city. I guess the new IT opulence has brought in pubs and gigs only (it is common for Indians to end almost every sentence with ‘only’).

Yesterday, I picked up my son Jodha Singh from the pre-school he is enrolled in here. His teacher said, he wouldn’t play Holi (“Festival of Colors”—though bastardized; some “celebrants” today throw sewerage on people as well!). Now, the legend of Holika is vanishing and so too the spirit of post harvesting thanksgiving prayer to the Almighty. Apparently, Jodha was upset when other children were throwing water and colors on him. I told Miss Priya that his aversion may have come because he has not partaken in this festival as the Sikhs of Panjab have a little reason to celebrate. She wasn’t sure how to respond; do most Panjabis and Sikhs know how to “play Holi?”

It was only a matter of time. Indira Gandhi created many myths during her tyranny. She created the myth of herself as ‘Kali’, the goddess of destruction following the war in Bangladesh in 1971. She created the myth of herself as “Mother India”, with a strong matriarchal love and care for her subjects. However, the most important myth that she helped create that has long captivated western audiences was the foundational myth of India’s independence – the nonviolence of Gandhi.

It was only a matter of time. Indira Gandhi created many myths during her tyranny. She created the myth of herself as ‘Kali’, the goddess of destruction following the war in Bangladesh in 1971. She created the myth of herself as “Mother India”, with a strong matriarchal love and care for her subjects. However, the most important myth that she helped create that has long captivated western audiences was the foundational myth of India’s independence – the nonviolence of Gandhi.

Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi is one the most well-known films about the subcontinent. In 1982, the movie was awarded the Best Picture by the Academy Awards. Ben Kingsley, who played Gandhi, and the director, Attenborough, also received individual credits. However, few have ever delved into the politics in the movie’s creation. In many ways, we find ourselves far removed from the world of art and into the territory of propaganda.

The funding of the Gandhi was highly unusual. Fully one-third came directly from the national treasury – could we ever contemplate money coming directly from the Treasury Department to fund a commercial, errr I mean movie? Propaganda at its best requires whitewashing and in the film we see a guiltless Nehru, the evil villain Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and a de-Hinduized Gandhi, without patriarchy, caste prejudices, or hypocrisy.

It was to be expected as the screenplay was checked and rechecked throughout the whole process, often directly by the then-Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi herself. Many noted that the opening credits of the film should have had the message: “The following film is a paid political advertisement by the government of India.”

I leave out a discussion for M. Gandhi for now, but will hope to take it up later. For now, we focus on the film. The success of the movie in terms of cultural capital cannot be emphasized enough. It was this movie that helped solidify the myth of India as related to Gandhi – overthrowing colonial rule, nonviolent, and wedded to the belief of equality for all. Indira Gandhi’s purchase still continues to reap rewards for India almost three decades later.

We now get the sequel.

Yet another inexplicable case of profiling has come to light. On January 26th, 36 year old Rashad Bukhari arrived from Pakistan with a valid multi-entry visa into the US. Bhukhari is a former employee of the U.S. Institute for Peace, and currently the Urdu-language editor of the Common Ground News Service, whose goal is to build bridges between the Muslim world and the West. The news service is funded by the Search for Common Ground, a conflict resolution and conflict prevention ngo.

Yet another inexplicable case of profiling has come to light. On January 26th, 36 year old Rashad Bukhari arrived from Pakistan with a valid multi-entry visa into the US. Bhukhari is a former employee of the U.S. Institute for Peace, and currently the Urdu-language editor of the Common Ground News Service, whose goal is to build bridges between the Muslim world and the West. The news service is funded by the Search for Common Ground, a conflict resolution and conflict prevention ngo.

Immigration officials at Dulles could have easily verified all of this if Rashad had been allowed to make a phone call or if they themselves had chosen to check. Rather, they detained him for 15 hours, temporarily took away his cellphone and laptop, and eventually put him on a plane back to Pakistan. They prepared a transcript of the encounter in which an official justifies the United States not honoring Rashad’s visa by saying, “You appear to be an intending [sic] immigrant.” [Washington Post]

Bukhari was refused entry because the immigration agent he spoke with found that he was an “intending immigrant” or that he had an intent to remain in the US. His visa was a temporary visa (probably visitor). However, Bukhari has a wife and three children in Pakistan, a return ticket there, and a good job, all of which would normally indicate that he has no intention of remaining here in the US. The number of connections you have in your home country is what determines whether you have ‘an intent to remain’ in the US, and Bukhari’s connections, in ordinary circumstances, would be more than enough to assure authorities that he would return to Pakistan.

In words that don’t appear on the transcript of the case, the official told Bukhari that he could “voluntarily” withdraw, return to Pakistan, and reapply for another visa, or face a five year ban. So he left, and now faces the consequences that accompany being refused entry at a border.