A few weeks ago, I was invited to participate in a planning and brainstorming retreat for an innovative pilot project that Union Theological Seminary is launching this summer. UTS, which has a longstanding commitment to social justice, are aiming to bring together a group of 30 young(ish) (21-35 year old) leaders from different religious and spiritual backgrounds for five days in New York City this July to explore the intersection of faith and justice and build a stronger spiritual activist movement together.

The Millennial Leaders Pilot Conference will take place July 13th to 17th at UTS in Manhattan. All travel and room and board expenses will be covered for participants, who should have histories of doing social and economic justice work in their respective communities. According to the conference website, applicants “may be community organizers, staff of NGO/NPO, in ordained or lay service to a local church or religious community, as well as they may function is less official leadership roles. Formal affiliation with a specific religious tradition or community is not a prerequisite and people with no affiliation are encouraged to apply. In this regard, the only formal requirement is an interest in the intersection between spirituality and activism.”

This promises to be an exciting and unique gathering with the potential of building a more long-term, sustainable movement of activists and organizers from different faith traditions. At the planning retreat, many of us discussed how questions of spirituality and religion are so often left out (or are even taboo sometimes) in progressive social and economic justice spaces. And on the other hand, which we often discuss here at The Langar Hall, social and economic injustices are so often perpetuated in the name of religion, including Sikhi.

If these ideas resonate with you, I hope you’ll consider applying and spreading the word to your friends, family, and colleagues, Sikh and non-Sikh alike. All the details about the conference and the application can be found here. The deadline to apply is the end of the day this Friday, May 23rd.

When most of us imagine what the people inside immigration detention centers in the United States look like, we usually do not  think of Sikhs from Punjab. Our Sikh American community — and more broadly South Asian American community — has been reluctant to deeply engage with the harsh realities of immigration policy and detention here in the United States. Too often we have seen this as someone else’s issue or passed quick judgment on those migrants from various parts of the world who overstayed their tourist visas or crossed the border under the radar — in search of work, to feed their families, in hopes of a better life. Papers or not, this hope for freedom is what brings all migrants to the United States.

think of Sikhs from Punjab. Our Sikh American community — and more broadly South Asian American community — has been reluctant to deeply engage with the harsh realities of immigration policy and detention here in the United States. Too often we have seen this as someone else’s issue or passed quick judgment on those migrants from various parts of the world who overstayed their tourist visas or crossed the border under the radar — in search of work, to feed their families, in hopes of a better life. Papers or not, this hope for freedom is what brings all migrants to the United States.

Right now at least 37 Punjabi migrants, who fled India in search of this illusive freedom, are detained in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in El Paso, Texas. News of these men and others at the El Paso facility protesting their indefinite detentions (they have been detained for over nine months now) came to surface in December. Last week, we learned that 37 Singhs — now known as the El Paso 37 — began a hunger strike.Â

37 young Sikh men — many who are seeking political asylum in the US — have been detained for almost a year in Texas, yet we have heard almost nothing about it in our organizations or gurdwaras. There has been no major news coverage of these men’s plight. Their harsh journey to El Paso reportedly took them through Moscow, Havana, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. Instead of finding respite, comfort, and safety in the US, they have found prison walls.

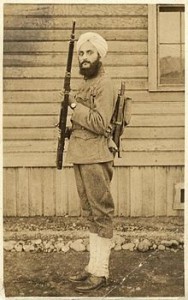

Yesterday, the Washington Post reported that a bipartisan group of 105 Members of Congress sent a letter urging the Department of Defense to end a presumptive ban on devout Sikhs who want to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.  Over the past several years, civil rights group, The Sikh Coalition, has been working to address the issue of equal opportunity in the Armed Forces allowing all Sikhs to serve.  Since 2009, three Sikh Coalition clients—Major Kamaljeet Singh Kalsi, Captain Tejdeep Singh Rattan, and Corporal Simran Preet Singh Lamba—have received rare and historic accommodations to serve in the U.S. Army with their articles of faith intact.  A timeline of the efforts can be found here.

Yesterday, the Washington Post reported that a bipartisan group of 105 Members of Congress sent a letter urging the Department of Defense to end a presumptive ban on devout Sikhs who want to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.  Over the past several years, civil rights group, The Sikh Coalition, has been working to address the issue of equal opportunity in the Armed Forces allowing all Sikhs to serve.  Since 2009, three Sikh Coalition clients—Major Kamaljeet Singh Kalsi, Captain Tejdeep Singh Rattan, and Corporal Simran Preet Singh Lamba—have received rare and historic accommodations to serve in the U.S. Army with their articles of faith intact.  A timeline of the efforts can be found here.

The Members wrote:

Dear Secretary Hagel,

We respectfully request that the United States Armed Forces modernize their appearance regulations so that patriotic Sikh Americans can serve the country they love while abiding by their articles of faith.

Devout Sikhs have served in the U.S. Army since World War I, and they are presumptively permitted to serve in the armed forces of Canada, India and the United Kingdom, among others. Notably, the current Chief of Staff of the Indian Army is a turbaned and bearded Sikh, even though Sikhs constitute less than two percent of India’s population. Throughout the world, and now in the U.S. Army, Sikh soldiers are clearly able to maintain their religious commitments while serving capably and honorably.

After hearing from their constituents, many Members of Congress who represent large constituencies of Sikhs signed onto this letter representing the importance and value of political engagement. Â Unfortunately, there were also Members of Congress – some who represent Sikh constituents, who fund-raise within the Sikh community and even sit on the American Sikh Congressional Caucus who did not sign this letter. Â This includes my own Member of Congress, Devin Nunes who “represents” (or that’s what we thought) a large constituency of Sikhs in the Central Valley of California. Â Other missing signatories include Congressman LaMalfa and McClintock – who, in the past, have reached out to the Sikh community for support.

It isn’t enough to simply invite Members to our Gurdwaras and offer them saropay. Â We have to hold our Members of Congress accountable once they leave our Gurdwaras and are challenged to support our issues on the Hill. Â Our presence and political engagement will only make a difference when we continue to take a leadership role to address inequity in our society and establish a strong voice on behalf of the Sikh community.

Blogged by Harjit Singh

Blogged by Harjit Singh

Many people who know me wonder why as an astrophysics and geophysics major I interned in the office of Congresswoman Judy Chu. In her office I have was not only able to explore my interests, but I also served my Sikh community and built a network of friends and mentors who will likely be there for me as I ready to launch in the world- post- undergrad.

As an astrophysicist, I was assigned to conduct research on NASA’s priorities and goals. I read the Congressional Research Survey Reports about NASA, attended hearings on the topic of NASA reauthorization, and wrote memos summarizing those hearings. The internship helped me to understand the future of space exploration and become somewhat of an expert in the policy aspect of this field.

One of the highlights was meeting Bill Nye at a NASA event I attended through my internship. This man helped many kids fall in love with science so meeting him was inspirational.

In terms of advancement of Sikhs, I believe I contributed to the cause during my time in D.C. First, it was a positive step adding to the diversity but specifically increasing the Sikh presence and visibility in the city, especially on Capitol Hill. Even in a city filled with graduate and professional degrees, there remains much ethnic and religious ignorance. Luckily, I had the opportunity to dispel some of that ignorance through my daily interactions with people. Also, with Judy Chu being a co-chair of the American Sikh Congressional Caucus, I worked on a few cool things for the caucus. My most important contribution would have to be writing the first draft to a resolution (H.Res. 334) that was introduced in Congress to commemorate the anniversary of the shootings at the Oak Creek Gurdwara.

Op-Ed printed in The Harlem Times Nov/Dec Issue

White supremacy typically evokes images of Klansmen on night rides setting homes ablaze with burning crosses or white policemen hosing down African American protesters during the civil rights movement. However, white supremacy is also what led a group of black teenagers to violently attack a Sikh man in Harlem this September. Given that the attackers are not white, how then is white supremacy related?

Early reports indicated that a group of 15-20 young boys assaulted Dr. Prabhjot Singh yelling “Terrorist†and “Get Osama,†leaving him with several injuries including a fractured jaw. What Dr. Singh experienced is not an isolated incident. Though violence against Sikhs has increased in the last 10 years and some attribute this to 9/11, it is part of a much more complex narrative that pre-dates 9/11: long-standing histories of oppression and genocide of Sikhs in pre-colonial and post-colonial India as well as systemic racism in the U.S. Media reports of the attack against Dr. Singh have followed an almost prosaic plot, identifying post 9/11 backlash, Islamophobia, racial profiling and misidentification as the usual suspects but failing to address white supremacy as a root cause in both the past and present.

Though police have not yet identified the attackers, accounts from Dr. Singh and eyewitnesses intimate that his aggressors were young black boys. When Melissa Harris-Perry interviewed Dr. Singh, she remarked on her surprise that his assailants represent a group also targeted by racism. However, it is precisely their experience as targets of racism which likely motivated them. Black males continue to be targeted and profiled as dangerous or unsafe or less competent at work and school, as evidenced recently by the NYPD’s use of stop and frisk tactics and the murder of Trayvon Martin. Historically, groups systematically targeted by racism scapegoat other groups that pose real or perceived threats. During the founding years of the United States, divisions between communities began when slavery and colonialism were the reality of white on black relations. Tensions between people of South Asian and African heritage have an equally long history, spanning the 19th century when Indians first immigrated to Africa and the U.S. Lastly, race still defines our society, the way we see ourselves and other groups of people as it has for centuries though now in a more diverse context.

In many ways, what Dr. Singh experienced was similar to the way Irish, Jewish and Japanese immigrants were scapegoated in the 19th and 20th centuries in the U.S. (more…)

BREAKING NEWS: The Sikh Art and Film Foundation has responded by including a female speaker in next week’s Leadership Summit!!! Great progress. Â Yet, the lack of representation of women and girls from 2004 – 2012 in the film festivals and galas still needs to be addressed, and this is a community wide issue. Â See below for actionable solutions.

Via Email:

November 15, 2013 7:43PM Nina Chanpreet Kaur,

Dear Sikh Art and Film Foundation,

I am very glad to see that Rashmy Chatterjee will be speaking at next Friday’s Leadership Summit.  This is a tremendous gain for our community as most of the speakers at the summit have been men since 2011.  This represents a trend in many Sikh organizations I hope we can change together. As a Sikh woman and resident of NYC for the last 11 years, I have followed your organization since it’s inception.  Over the years, I have attended many of your events and have been so inspired by the films, speakers and attendees.  I have also noticed the lack of representation of women and girls in your programs.  Though you took a step forward this week, I believe you could be doing more to address, highlight and celebrate the challenges and triumphs of Sikh women and girls whether in your Film Festival, Heritage Gala or Leadership Summit.

I understand that your goal is to transcend the dichotomies and binaries of gender and other categories to sustain the universality and equality that our Gurus envisioned in order to promote and preserve Sikh and Punjabi heritage. Â I share your vision and do not condone a gender binary or bias towards either men or women. Â I am also aware that you face limitations as all organizations do, in particular that you must base the selections of films on the submissions you receive. Â However, Sikh men and boys have been a central part of your programs in a way Sikh women and girls have not and this indicates a bias – whether intentional or not.

From 2007 to 2012, none of your Gala awards for Leadership and Vision have been presented to Sikh women. Â In fact, the only women who received awards were for Creativity/Art with the exception of Shonali Bose who received an award for Courage and Shelley Rubin who received an award for Leadership jointly with her husband. Â For 5 years in a row you have only presented Sikh women with awards for Creativity/Art and no other category. Â As a Sikh woman, this sends a message to me and the next generation of Kaurs that women can be honored for creativity and art but not for leadership and vision. Â It raises questions about your beliefs and assumptions related to gender roles and women’s capacities in relation to men. Â This is most certainly not the message young Kaurs should be receiving, nor do I think this is your intention based on the email I received from Ravi last week. Â Â Â Â (more…)

Guest Blogged by Jaideep Singh

As the Sikh American community embarks yet another mobilization against hate attacks— since this latest episode of violence has really hit home with many Sikhs in a way rarely seen since Balbir Singh Sodhi— we would do well to first answer the difficult, necessarily critical questions posed by my sister Nina Chanpreet Kaur in her thoughtful, passionate piece from last year.[1]

Our efforts at “education and outreach†clearly have yielded perilously little success— as measured by the safety of our communities. So education obviously is NOT enough. Reality is far more complex and ugly. A person who would attack a gurdwara is not coming to an open house or community feeding (langar) to abate their hatred. The long list of those in our communities who have been injured and killed, and the homes and gurdwaras defaced, testifies to as much. We cannot advance by hiding in our gated communities, far from the raw racial realities daily faced by our less fortunate sisters and brothers.

Fighting centuries of entrenched, utterly irrational white [and Christian] supremacy is neither an easy task, nor a short term one. Many of us cannot even bring ourselves to admit these forces even exist, let alone how they permanently define Sikhs as racial and religious outsiders. That naïve approach must end, replaced by a sophistication borne of serious historical study of U.S. history.

Guest blogged by Simran Jeet Singh

Last night, I received the kind of phone call that everyone dreads: a close friend was hurt, and on his way to the hospital. But the news got worse, as I learned that my friend, Dr. Prabhjot Singh, a young Sikh American professor at Columbia University, had been brutally attacked on a public street, the victim of a violent hate crime. My brother and I immediately jumped in a taxi and rushed to the hospital, where we finally saw Prabhjot being wheeled in, bloody and bruised, his face swollen from a fractured jaw. He couldn’t speak because many of his teeth had been displaced, but he waved limply to let us know that he was okay.

We joined Prabhjot in his hospital room and were surprised to find it already filled with officers from the NYPD and its Hate Crime Task Force. As he struggled to give his statement, we came to learn that his assailants had taunted him as they beat him, calling him “Osama” and “terrorist.” He described being punched in the face repeatedly until falling to the ground. And then he recalled how the punches to the head continued as he laid on the sidewalk.

I saw Prabhjot shudder as he realized how much worse it could have been. He had just returned from dinner, dropping his wife and one-year-old son at home before going for a walk. He reached from his hospital bed and grabbed his wife’s hand.

He recounted the scariest moment, seeing a young male put his arm inside his coat, as if reaching for a gun. He also remembered people pulling at his long beard. He couldn’t provide any descriptions about his assailants, and it seemed to me that in some way, he didn’t want to remember them.

Prabhjot has dedicated his life to serving the underserved. He is currently the Director of Systems Management at the Earth Institute, and he draws upon his experiences abroad to help improve the health of local communities like Harlem. In addition to serving as an Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, he is also a resident physician at Mt. Sinai Hospital. His life’s work has been to help the underprivileged access quality and affordable healthcare, and he believes strongly that his countless hours of service are an investment in improving the health of impoverished communities.

Guest blogged by Simran Jeet Singh

As I strolled outside my Manhattan apartment this morning, reflecting on the Trayvon Martin decision, I had one of those moments that would shatter any possible artifice of living in a post-racial society.

shatter any possible artifice of living in a post-racial society.

I heard a woman cry in pain and turned around to see her lying on the street, clutching her bleeding knee. I rushed over and extended my hand to help her up. She looked up and her entire body recoiled the moment she saw that my face was adorned with a turban and beard. She shook her head and muttered “foreigners…” just loudly enough so that I could hear. I stepped away, understanding her reaction, and I turned to hold the traffic as she gathered herself.

I watched her limp to the sidewalk and was surprised when she looked back at me over her shoulder and mouthed the words “thank you.”

And I realize now that I should have thanked her. She reminded me that despite being a social construct, race is absolutely real in our world, and in the rules of this game, so many of us find ourselves to be the typecast. It’s a lesson we receive repeatedly throughout our lives, but it bears repeating for a reason.

To forget the rules of the game is to forget the reality in which we live. As Keyser Soze said in The Usual Suspects, “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

I’ve been invited to and participated in a number of interfaith gatherings, conferences, retreats, and discussions over the years. Time and time again I find myself being the only Sikh in these spaces. And often find that the well-meaning, progressive faith-based activists in these spaces don’t know other Sikhs besides me nor do they know much about Sikhi. So then it was refreshing to hear about the 2030 Faith in America Challenge, an interfaith gathering to strategize around creating a more just society, from a Sikh friend who is helping organize it. On October 6-7, the Nathan Cummings Foundation will host leaders in the 20s and 30s for a retreat in upstate New York to explore important and urgent questions around religious diversity. The application deadline is Monday, July 15th! Check it out and consider applying. Sikh voices are greatly needed in this discussion.

More information follows, and visit the website here.

In a rapidly changing world, where faith is as often a force for inspiration as well as polarization, how might we as people of faith, support individuals and communities connected to their religious and spiritual identities, to amplify their voice, vision and public leadership?

Is this a challenge that resonates with you or keeps you up at night? Would you invest four days of your life to wrestle with this challenge with a diverse group of leaders?

If yes, we invite you to complete an application to join us for the 2030 Faith in America Challenge gathering application due on by Monday, July 15, 2013. If selected, travel, food and lodging will be covered by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Below you will find the articulation of the broader context in which we are locating this challenge, our belief in the importance of a strong religious and spiritual voice in the public arena, information about outcomes, methodology, profiles of potential participants, and a Frequently Asked Questions section.

Please review the required preparation and questions and please submit the completed application online by 11:59pm EST on Monday, July 15, 2013. Please send questions to 2030Challenge_FIA@nathancummings.org.

Christina Antonakos-Wallace, filmmaker of with WINGS and ROOTS

Christina Antonakos-Wallace is the filmmaker behind with WINGS and ROOTS, a 90-minute documentary that tells the stories of five people from different immigrant communities living in New York or Berlin, Germany, who have struggled to shape their identity in various ways.

The film features The Langar Hall’s own Sonny Singh, a Sikh living in New York. Part of his story was featured in the well-received short documentary Article of Faith, spawned from the with WINGS and ROOTS project, that portrays Sonny’s activism around bullying of Sikh school children in New York. Another short film, called Where are you from from? was also produced out of this project.

Below, Christina Antonakos-Wallace discusses the film and provides great insight about its intended message regarding the immigrant experience and the search for identity. You can view the trailer for with WINGS and ROOTS at the end of this post.

University of Massachusetts – Boston

Department of Counseling and School Psychology

100 Morrissey Blvd, Boston, MA 02125-3393

University of Massachusetts Boston

Researcher: Dr. Kiran S. K. Arora

Study: Religious Discrimination and Race-Related Stress among North American Sikhs.

We are interested in conducting research with Sikhs living in North America. The purpose of the study is to examine how experiences of religious discrimination and race-related stress may impact the relationships, mental health, and overall well-being of Sikhs. To gather this information, we are looking for individuals over the age of 18, who self-identify as Sikh, and are living in North America, to complete a set of anonymous questionnaires online.

This study hopes to contribute to a dearth of academic literature on Sikhs and their families. Your contribution is valuable, as it would provide insight for family therapists and other mental health professionals working with Sikh families. Your participation is strictly voluntary. Confidentiality is of utmost importance, and measures will be taken to protect your identity.

The purpose of this announcement is to alert you to the research project and invite you to ask any questions you may have about this project. You may contact Dr. Kiran S. K. Arora at Kiran.Arora@umb.edu if you are interested in participating, or learning more about the study. To learn more about the study or participate, you may also go to https://www.psychdata.com/s.asp?SID=153728.

In a process that took three decades, Sajjan Kumar, a leader in India’s Congress Party, was recently acquitted for his well-documented involvement in the anti-Sikh pogroms during November 1984 in which thousands of Sikhs were murdered in three days in the country’s capital city. Five co-accused were convicted. (Source: Live Mint)

About two months ago, I observed the continuing engagement by representatives of the Indian government with the Sikh American community, which in that instance took the form of an exhibition on Sikh heritage in Atlanta, Georgia, sponsored by the Government of India. This exhibit has just recently been presented in Washington, D.C., as well, and it is consistent with increased engagement and activity related to the Sikh American community — be it directly, or through lobbying of US officials — by representatives of India. The increasing effort by Indian officials to promote the Sikh community in the United States is problematic, however, as it runs contrary to India’s track record with the Sikhs in its own borders over the past several decades.

Whether in the aftermath of a hate crime (such as in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, or recently in Fresno, California), or in what appears a deliberate attempt to brand the Sikh identity with Indian nationalism, representatives of the Indian government are insisting that they be the custodians of the Sikh community in the United States.

As you have probably heard by now, Boston is reeling in the aftermath of a few explosions near the Boston marathon this afternoon. Two people  have been killed and dozens injured and being treated at local hospitals. I’ve been texting, calling, and checking up on friends in the area all afternoon. We are all shook up and confused by what is happening, searching for answers or explanations for something so hard to comprehend (though something commonplace in other parts of the world like Pakistan, where 4 were killed by a US drone yesterday, and Iraq, where over 50 were killed in a bombing today). Very little is yet known about who did this and why, but of course, the mass media are already making lots of unsubstantiated claims, while accusations and assumptions are spreading quickly on Twitter and Facebook.

have been killed and dozens injured and being treated at local hospitals. I’ve been texting, calling, and checking up on friends in the area all afternoon. We are all shook up and confused by what is happening, searching for answers or explanations for something so hard to comprehend (though something commonplace in other parts of the world like Pakistan, where 4 were killed by a US drone yesterday, and Iraq, where over 50 were killed in a bombing today). Very little is yet known about who did this and why, but of course, the mass media are already making lots of unsubstantiated claims, while accusations and assumptions are spreading quickly on Twitter and Facebook.

As something as horrifying as this afternoon in Boston is literally unfolding, as we are worrying about loved ones who may be affected, we already have to worry about the consequences of backlash violence. We have to worry about the sensationalism in the media. We have to worry about being attacked because of the color of skins, the turbans or hijabs on our heads, the beards on our faces. I pray that people in the United States and beyond have learned something in the last 11 and a half years. I pray that the collective response to today will be drastically different from the knee-jerk racism that pervaded the days, weeks, months, and years after 9/11/01.

But honestly, I’m not so sure how hopeful I am.

“Indians, many of whom were Sikh, worked at the Hammond Mill before its demise in 1922. During that time period, the Indians left their mark on Astoria, participating in wrestling matches, occupying Alderbrook also known as “Hindu Alley,” and forming the Ghadar political party. Courtesy of Clatsop County Historical Society.” (source: The Daily Astorian)

One of the legacies of the earliest Sikh and Indian immigrants to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century was the creation of the Ghadar Party, a political movement based in northern California that sought to promote India’s liberation from British rule.

Led by Indian expatriates in the United States, the Ghadar Party was formed in 1913. One of its main activities was the publishing of literature to promote resistance to British rule and for a free India. Obviously a threat to the ruling class, the literature was banned in India, and upon their capture, the Ghadarites were often imprisoned or executed as terrorists by the British.

This year, the San Francisco headquarters of the Ghadar Party has been opened to the public by the Indian Consulate as a museum. The printing press that the Ghadar Party used to print their literature is also now on display at the Gurdwara in Stockton, California. However, while it was previously believed that the Ghadar Party was founded in California, historians now place the genesis of the movement further north in the state of Oregon, where Johanna Ogden recently mapped a forgotten (and primarily) Sikh settlement of laborers in 1910 known as “Hindu Alley”.

“The bodies of Shindiver Grover, 52, his wife Damanjit, 47, and their two sons, Sartag, 12 and Gurtej, 5, were found in their first-floor apartment in Johns Creek, Ga., at around 11:30 a.m. Monday, according to local reports.”

(Source: NY Daily News. Photo credit: CBS Atlanta)

Tragic news broke today that a Sikh family in Atlanta, Georgia, was found dead in their home. The bodies of father Shindiver Grover (52), mother Damanjit Grover (47) and their two sons, Sartaj (12), and Gurtej (5), were discovered in their apartment when Damanjit did not report for work on Monday.

Police are still investigating what is called a “complicated” crime scene, but believe it was a murder-suicide:

The nature of the murder – the city’s first since it was incorporated in 2006 – was troubling to even the most senior investigators, [Johns Creek police Chief Ed Densmore] said.

“We are all human. We’re all parents. We have families,” Densmore said, according to local CBS News.

“You deal with something like this, it will take a little bit out of you, of course.”

Few details have been released at this point. Prayers for the departed souls and condolences are offered to those who knew the family.

While we are still learning about the tragedy, Sikhs in the United States who are seeking resources to deal with domestic issues can contact the Sikh Family Center, who provides a confidential “culturally specific peer-counseling and non-emergency support for community members in Punjabi and English.” The Sikh Family Center message line can be reached at (408) 800-SEVA or (408) 800-7382.

For more immediate needs, the National Domestic Violence Hotline is available in 170 languages at 1−800−799−SAFE (7233). In case of emergency, always first call 911.

[Cross-posted on American Turban]

Most of us are probably familiar with the history of the first wave of Punjabi migration to California in the late 1800s and early 1900s.  These pioneers, many Sikhs, set up the country’s first gurdwara in Stockton, formed the Ghadhar Party to overthrow the British Raj, and many ended up marrying Mexican women. I learned about this fascinating history way later than I should have, but have noticed more and more consciousness of these early migrants and their descendants over the last several years.

These pioneers, many Sikhs, set up the country’s first gurdwara in Stockton, formed the Ghadhar Party to overthrow the British Raj, and many ended up marrying Mexican women. I learned about this fascinating history way later than I should have, but have noticed more and more consciousness of these early migrants and their descendants over the last several years.

A book that just came out unearths a lessor known history of early South Asian migration to the United States. A few decades after this Punjabi migration to California came a smaller, but no less interesting wave of South Asian immigration (Bengalis) to the east coast.  This little-known history is documented in a new book by Vivek Bald called Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. Like their Punjabi predecessors in California, these mostly Muslim migrants were working class, dealt with a great deal of racism, and married women from other communities of color and immigrant communities.

Bald, also a filmmaker (who made an amazing film about the British Asian underground music movement of the 1990s called Mutiny: Asians Storm British Music), is also working on a documentary version of the book entitled In Search of Bengali Harlem, which you can preview here.

I haven’t yet read the book but am really looking forward to checking it out. As you’ll see from the blurb below, these stories have much in common with those of the early Punjabi migrants, even if they were working in different industries and came from different parts of South Asia.

Guest blogged by Simran Jeet Singh

Last week, people around the world watched a Sikh with a turban and beard – Gurpreet Singh Sarin – charm the judges on the iconic television show, American Idol. The show’s judges and producers played up his nickname, the Turbanator, and almost immediately, #Turbanator began trending nationwide on Twitter. As is often the case, however, the ugly face of bigotry reared its ugly head and reminded us all of the problems faced by Sikhs around the country. Countless Americans equated the contestant’s turban and beard with terrorism, and #Osama also began trending across the country.

Last week, people around the world watched a Sikh with a turban and beard – Gurpreet Singh Sarin – charm the judges on the iconic television show, American Idol. The show’s judges and producers played up his nickname, the Turbanator, and almost immediately, #Turbanator began trending nationwide on Twitter. As is often the case, however, the ugly face of bigotry reared its ugly head and reminded us all of the problems faced by Sikhs around the country. Countless Americans equated the contestant’s turban and beard with terrorism, and #Osama also began trending across the country.

Gurpreet has little control over how the producers of American Idol choose to project his image. Yet he has done an incredible job of working within the system to create positive change, and his breakthrough performance is something from which we will all benefit for years to come. More importantly, we as a community cannot learn how to build our image in greater America if we do not see Sikhs experiment within mainstream media and learn from those experiences. Certainly there were moments on the show that could have been improved, and while it is important to recognize and build upon these for the future, it is also important for us to take this moment to enjoy this unprecedented moment in our community’s history.

(Disclaimer: I’ve never watched American Idol before. It’s true.)

Most of you are probably already well aware that a young Sikh named Gurpreet Singh Sarin appeared on American Idol last night and made it through the first hurdle. In case you missed it, here is the clip from his audition in front of the judges.

Like most of you, I’ve been barraged with posts on Facebook and Twitter about Gurpreet’s success on the show last night, mostly expressing excitement and support for the self-proclaimed “Turbanator.” The vibe I’m getting from all the posts I’m seeing from Sikhs is that this big moment for Gurpreet is a big moment for the Sikh community in the US, perhaps an opportunity for some positive representation in popular culture. The Sikh Coalition and SALDEF have tweeted congratulations to Gurpreet as well, and the overall sentiment appears celebratory.

I share some of this excitement, or at least fascination, but the whole thing is also making me cringe a bit. I don’t want to unnecessarily rain on this parade because I do think it is an interesting moment and opportunity. I also think Gurpreet is a solid singer and did a great job at handling what must have been an uncomfortable situation on many levels.

Co-blogged with Nina Chanpreet Kaur

(source: Daily Record and Sunday Mail)

“All the talking is done and now it’s time to walk the walk / Revolution’s in the air 9mm in my hand / You can run but you can’t hide from this master plan.” (Song lyrics by Wade Michael Page’s band End Apathy)

A few weeks ago, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) closed its investigation into the mass shooting that occurred at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in August, in which six Sikhs were murdered and wounded four others, including Lieutenant Brian Murphy of the Oak Creek Police Department, and Punjab Singh, who is still in a long-term care facility receiving treatment.

The FBI’s conclusion does not bring any closure. In the wake of Oak Creek, the specter of a growing white supremacist movement has not been adequately addressed by the media, policy makers, nor law enforcement agencies. This frames the issue of hate crimes against Sikhs as something almost incidentally perpetrated by independent murderers, and the stalling by the FBI to accurately and consistently report anti-Sikh and other hate crimes as well as link it to domestic terrorism reinforces the sense that the white supremacy movement is something federal, state and local government are not taking seriously or prioritizing. Historically, the white supremacist movement at-large has perpetrated heinous crimes fueled by hate and bias often in the guise of a member gone rogue as we saw in Oak Creek in August 2012.