We have often heard about the Sikh regiment in the British and Indian Armies. Recently, the Gurkhas, a South Asian group, who also has made-up a large portion of the British Army, are seeing a U-turn in an earlier policy that did not allow Gurkhas soldiers to settle in Great Britain.

The Tribune reports:

In a U-turn of its earlier policy, Britain is set to allow an estimated 36,000 Gurkhas who served in the British Army before 1997 and their families to settle here, conceding a long-pending demand by the former soldiers.

The home office was forced to take action after a ruling from high court judges in October that the government needed to review its policy on whether the Gurkhas who had served the army before 1997 — the year Hong Kong was handed over to China — could live in Britain.

However, the Nepalese government is concerned about the loss of so many soldiers and their families along with their army pensions, that they have warned the Home office that, “ … Nepal might scrap the 1947 agreement under which its young men have been recruited each year” to serve in the British Army. Since the signing of the agreement, the Nepalese economy has heavily relied on the army income.

Is the question facing Sikhs in Oxford, England, as they try to find a central location to pray as a sangat without having to convert private property into religious property.

Is the question facing Sikhs in Oxford, England, as they try to find a central location to pray as a sangat without having to convert private property into religious property.

A religious community in Oxford is reeling after the city council ordered members of its congregation to stop worshipping at a house in Marston.

The city’s Sikh community has been meeting at 69 Cherwell Drive to pray for nearly three years. [link]

The neighbors’ chief complaints have been around parking and noise in the area. The story saddened me on two levels. First, because of the general difficulty Sikhs face in finding community space, and second, because of the underlying challenge to our practice of Sikhi.

Prince Harry has been roundly criticized for using the term “Paki” in refering to another miliary cadet and for suggesting that another cadet looked like a “raghead.” To his credit, he has apologized.

Prince Harry has been roundly criticized for using the term “Paki” in refering to another miliary cadet and for suggesting that another cadet looked like a “raghead.” To his credit, he has apologized.

What’s been interesting to me about this subject, first, is the discussion of whether Prince Harry deserves a pass. In a BBC article, Sunny Hundal, a Sikh, rightfully recognizes that the Prince’s casual use of “raghead” is troublesome. But, Hundal dismisses the attention paid to Prince Harry’s blunder as simple youthful indiscretion: “He’s a young person messing around and all the rest of it. Young kids say stupid things,” he said in the same BBC piece.

Sure Prince Harry is relatively young, but he is a public figure; more specifically, he is royalty who has had a fine education and upbringing, who has been on notice for years and years that what he does and says will be scrutinized and examined by the people. He should especially know this after his costume gaffe, in which he wore a Nazi uniform to a party. The mistakes of youth may explain some things, but Prince Harry is no ordinary person; nor is he so young that we can discount everything he says or does.

The other aspect of this story that piqued my interest is the apology offered by Prince Harry with respect to the “raghead” comment. On this point, a royal spokesman said, “Prince Harry used the term ‘raghead’ to mean Taliban or Iraqi insurgent.”

This apology totally misses the boat — the concern is not whether Prince Harry “meant” to apply the term to a certain group (even if the group is terrorists or horrible elements of our society); rather the concern is that the term itself is inherently inappropriate because it is used to brand and insult anyone that wears a headdress, including an Arab or a Sikh. In other words, using “raghead” does not suddenly become okay if it is correctly targeted. When it comes to this particular word, context does not matter — it is only used in a derogatory fashion, unlike other charged terms, like the “n-word”.

I hope Prince Harry learns his lesson and removes “raghead” from his vocabulary. I also hope he — or his staff — won’t come up with such lame explanations when and if he commits the next faux pas.

Today many Sikhs in Southern California will celebrate Guru Gobind Singh Ji’s Gurpurb. When I think of Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the first thing that comes to mind is the creation of the Khalsa as an army of the pure.

This past summer I was sitting in a group-discussion, with fellow 2nd generation Sikhs (amritdhari and non-amritdhari) in the West, where we were asked to share the first thoughts that came to mind when we thought of the term “Khalsa”. Here are some:

masculine, extremists, ego, amrit, air india bombings, khalistan, rules, khandha/militaristic, collective brotherhood, fiercely independent, love, panj pyare, historical of the past & raj karega khalsa

For myself, I thought it was interesting to see how the media (i.e. newspaper articles, calendars, and television) along with the politicalization of religion and translation of Sikhi between generations is influencing our perceptions of the Khalsa.

What are your thoughts? What do you think they reflect about the state of the Khalsa?

Hope all of you are enjoying your holidays with family and friends! Here is a “Punjabi” take on a Christmas and one of its infamous songs from my favorite British Comedy Show …. “Goodness Gracious Me”!

Some of you may have already seen it (GGM aired long ago, but is available on DVD-sets) … hope you have a great laugh after watching it!

Well I was hoping someone far more knowledgeable from our esteemed blog roster would write about this, but I figured since I feel it is extremely important and raises some critical issues, you’ll have to settle for me.

Well I was hoping someone far more knowledgeable from our esteemed blog roster would write about this, but I figured since I feel it is extremely important and raises some critical issues, you’ll have to settle for me.

Yesterday when I was watching CNN, Jasvinder Sanghera came on to talk about the recent release of Humayra Abedin.

For those that may not be aware, Jasvinder Sanghera is the author of a biography called Shame and the founder of Karma Nirvana, “[an organization] with a view to create support project for women who experienced language & cultural barriers.” I have read Sanghera’s memoirs and although her particular story of her parents’ attempt to force her into a marriage and the consequences she experienced is more extreme than most cases, still it echoes the larger problems of “forced marriage” in our community and differences may only vary in degree.

Jodha previously blogged about national-level elected Sikh leaders and rightfully noted the low representation of leaders from the UK. This week, Councillor Gurcharan Singh was chosen to represent the Conservatives as the Parliamentary Candidate for Ealing Southall. Ealing Southall has one of the highest proportions of Sikhs in any constituency in the UK and contains the Sri Guru Singh Sabha Gurdwara, one of the largest Sikh  temple’s outside of India. Chairman of the Ealing Southall Conservative Association, Manjit Singh notes,

temple’s outside of India. Chairman of the Ealing Southall Conservative Association, Manjit Singh notes,

“The people of Ealing Southall are fed up with Labour and want an MP who can make a difference. After the next election we will have a new Conservative Government led by David Cameron and a new Conservative MP for Ealing Southall in Gurcharan Singh. I look forward to taking our message to the voters and getting rid of this tired Labour Government and the local MP who is more interested in collecting his allowance than in serving residents.” [link]

Interestingly, Gurcharan Singh was one of five representatives who left the Labour party last year to join the Conservative party. Gurcharan Singh moved to the UK in 1972 and originally joined the Labour Party in 1976 and became a councillor in 1982. Last year, the Labour party faced internal division over their candidate selection and following Virendra Sharma’s selection several Sikh Labour councillors, led by Gurcharan Singh defected to the Conservative party. In June 2007 (and in the picture above with Tony Blair – Labour party) Gurcharan Singh said,

“I am full of hope for the future as this to me signals the beginning of an era where the Labour party can consolidate its leanings over the last few years and move forward with a new outlook based upon positive change. We progress.” [link]

Sorry for not posting last week…so here we go with the summary of the final part of the book. Next week will be the grand-finale as we try to pull all these pieces together and view the book in a comparative Sikh diasporic framework.

————————————————————————————-

Coblogged by: Jodha and Mewa Singh

Chapter 9 deals with “Punjabi, Bhangra, and Youth Identities” and the final chapter is the conclusion.

Chapter 9 opens with a discussion on the propagation of the Punjabi language in Britain. Since at least the 1960s members of the community have been worried about the decline in Punjabi language competency and in 1965 established the first Gurdwara-run “Punjabi school” in Smethwick.

During the 1960s-80s a series of laws were passed that sought to encourage support for minority languages. This resulted in the institutionalization of Punjabi at the GCSE and A levels. Despite these moves by the state and by the community (Punjabi broadcasting, newspapers, television stations), the general outlook of Punjabi’s future seems rather gloomy.

Last week we actually had a conversation about the book (thanks RT!) and hopefully this week will continue the dialogue. Sorry for the delay in getting this up, airline delays are tough. Here we continue….

———————————————————–

The chapters of this section probably also warrant separate blog posts as we tackle the subjects of Chapter 7 (“Employment and Education” and Chapter 8 (“Family, Gender and Sexuality”). Still time and space constricts us.

Chapter 7 looks at the employment and education profile of the Sikhs in greater detail than previously mentioned in Chapter 3. The authors note that the followers of Guru Nanak have done well in the UK, but by no means are they ‘ethnic high flyers’ (145).

Entering the UK job market as door-to-door tradesmen (Sikh Bhatras of the 1930s/40s) and followed by post WWII unskilled manual labourers, Sikh enclaves formed where employment opportunities were available. First jobs for newly arrived immigrants were facilitated by previously settled kith and kin.

Labour exploitation at the hands of factory managers and even intermediaries from their own community (batoos) helped to propel the labour movements led by the IWAs.

Coblogged by: Jodha and Mewa Singh

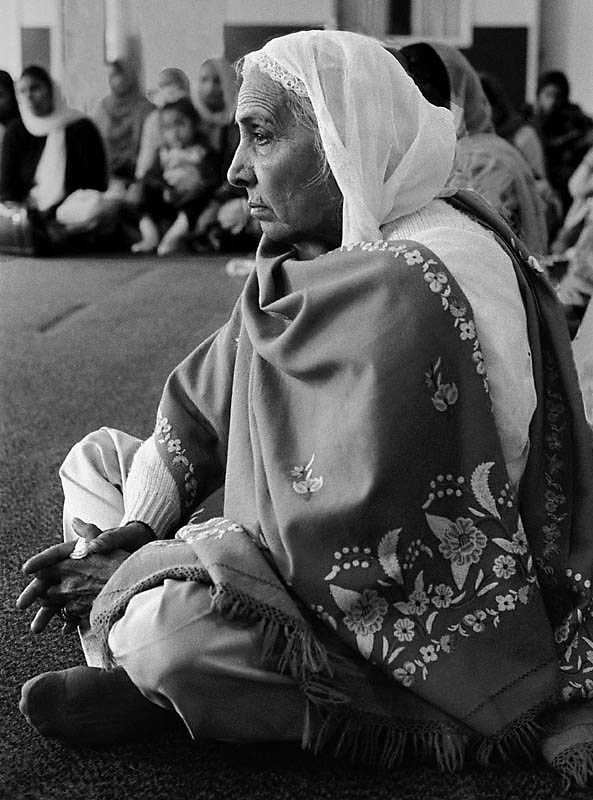

Well it doesn’t seem by the number of comments (0) that this first attempt at a book club garnered much interest, although by the number of hits, it has been extremely popular. Regardless, for us it has been a  great excuse to read a great book….So we’ll continue. PS: the side picture is related to a soon-to-be-available coffee table photography book.

great excuse to read a great book….So we’ll continue. PS: the side picture is related to a soon-to-be-available coffee table photography book.

———————————————–

The two chapters read this week probably deserve separate blog posts, but still in the interest of time and space, we are going to keep them together.

Chapter 5 deals with “Homeland Politics: Class, Identity, and Party” and Chapter 6 is about “British Multiculturalism and Sikhs.”

The authors begin chapter 5 by noting that:

Associations of immigrants in Britain have generally served two functions: to facilitate the integration of the new arrivals and as conduits of homeland politics, and these functions have further strengthened with the onset of globalization, which has underpinned the rise of nationalism and diaspora movements. (94)

1984 is seen as the ‘critical’ event that intensified Sikh religio-ethnic self-identification with large numbers of Sikhs. The mammoth protest at Hyde Park on June 10, 1984 may still be vividly inscripted upon the memories of many Sikh-Britishers.

Still the associations and groups that were created to manifest this new religio-ethnic self-identification and homeland politics were along the lines of traditional associations. While there was something new in what came out of the community after 1984, there are continuities as well.

Tracing the evolution of various causes within the Sikh community, the authors note moves from the politics of class (IWAs [Indian Workers Association] up to the early 1980s), to the politics of identity (Khalistan 1984-1997), to emphasis on political organization (Sikh Political Party, UK) (94).

Coblogged by: Jodha and Mewa Singh

After a suggestion from a fellow langa-(w)riter (thanks Reema!), we are trying a more thematic approach this week instead of summation. Let’s see how it goes:

——————————————————-

Chapter 3 and 4 this week had two very different topics. The third chapter begins by looking at the movements and changes in settlement, demography, and social profiles of the Sikh-British, while the fourth chapter concentrates on institution-building within the community at its chief site, the Gurdwara.

Issues of Settlement:

The story of Sikh settlement in Britain begins with Duleep Singh, the son of Sardar Ranjit Singh. After the defeat of the Sarkar-e Khalsa by the forces of the East India Company, Duleep Singh was separated from his mother, forced to renounce all claims and much state property, and later converted to Christianity, only to later reconvert to his ancestral faith towards the end of his life. While Duleep Singh’s story is an epic in and of itself symbolic of Sikh-Anglo relations, his migration to Britain was only to be the beggining of the Sikh presence.

Coblogged: Jodha and Mewa Singh

First off, our sincere apologies. Due to unforeseen circumstances, this could not be published on Monday. The rest of the days will go along much better. Also, bear with us as we will get better as we go along. So Ji Aayan Nu and welcome to TLH’s 1st Book Club

—————————————————————————-

The first chapter begins with a cursory summary of Sikh history. As the authors note (and in this section you can hear Gurharpal Singh’s voice a little more prominently), much of this chapter was published in his earlier Ethnic Conflict in India.

Beginning with the Guru period, the authors note that migration is hardly a new phenomenon for the Sikhs, nor can it be said to merely be a colonial phenomenon. Selectively touching upon aspects of Sikh history, the authors draw heavily from McCleod and Grewal as the more definitive accounts. However some of the debates in the field are noted as contrary to McCleod’s position of Guru Nanak lying within a ‘Sant tradition familiar to north India’, Sikhs regard the founder of their faith as one that created a ‘new religion for a new age’ (12).

UPDATE: Both authors – Dr. Tatla and Dr. Gurharpal Singh – said that they will participate in some capacity in our first book club. A number of well-known bloggers from some prominent websites have expressed interest as well. ORDER YOUR BOOK NOW! Only 1 week before we begin!

————————————————————

Coblogged: Jodha and Mewa Singh

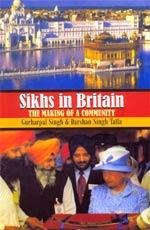

What we are about to suggest, to our knowledge has never been done before.

We are initiating the first TLH web-wide Sikh Book Club. At this point we are not sure of the frequency as we will gauge the interest from this first attempt.

What are we suggesting?

For the first book of our book club, we are suggesting a simultaneous reading of Gurharpal Singh and Darshan Singh Tatla’s Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community.

The two of us – Jodha and Mewa Singh – will facilitate the discussion (unless we can find someone better!). We plan to invite the authors as well as some prominent Sikh activists in our community. We hope Sikhs from all across the globe (especially UK Sikhs) will participate. Please feel free to invite others as well!

The Book:

Over the years we have read numerous academic books on the Sikhs and their history and the works of Gurharpal Singh and Darshan Singh Tatla have always been amongst our favorites. Thus, it was with great excitement that we see these two professors collaborating together. Both have an intimate knowledge of the Sikh community in England and we can think of few others that would be more able to write such a tome. This book, although focused on our brethren and sistren(?) in the UK, will provide us an avenue to delve into that section of our community, but we hope to broaden the conversation to understand other sections of our Sikh diaspora.

Often on this blog we have discussed what role our institutions should play in our lives and recently I had an opportunity to examine the issue anew. In a recent gurdwara council meeting I attended, one gurdwara decided to give a large sum of money to a group putting on a bhangra program. The group was not affiliated with the gurdwara. I will admit, I did not say anything at the time because I do not attend the gurdwara that decided to do this, but the incident did get me thinking about gurdwara funds and the concept of daswand.

When a gurdwara collects funds from the sangat – it does so under the pretence that the money is being collected to be put to some higher use, a use that we ourselves could perhaps not put it to, whether it be spiritual or practical. Usually we give the money as part of our daswand or some random seva to the gurdwara, but I think in every case it is understood that we are giving the money up to be put to a use that our Guru’s would have used it for – something necessary, something practical, and fundamentally “good.”

And as I write this post, some questions that I haven’t even answered for myself come to mind – Is the daswand I give to the gurdwara something I have a right to control – can I decide where it goes? If Sikhi is to be treated like a democracy, I would argue that absolutely I have every right to “vote” on where the funds go or at least have a chance to say something. But even in such a vote – should there be limits? Shouldn’t the funds of a gurdwara be spent on activities, which embody Sikh ideals and values? Presently, I am inclined to believe that sangat should have a say in where gurdwara funds are spent, but also that the options for spending funds should be limited to projects that actually embody and promote Sikh ideals.

But back to where we started – I brought bhangra up because it is something that can be debated – I’m not contending that it is an anti-Sikh activity, but at the same time, I don’t really think bhangra is something that perpetuates the Sikh way of life either. So I guess the dilemma in my mind in determining where the gurdwara should be spending its funds and where to draw the line…

So recently I came across a blog about all the “Stuff Korean Moms Like”. A Korean girl, Chiyo, who loves her KM (Korean Mom) decided to create this blog “to share the joy and dread of KM”. As I went through the list … I kept thinking about our own PSM’s (Panjabi Sikh Moms) … now now don’t think it’s funny to call our mummies’ PMS that actually stands for Panjabi Male Syndrome!

As I went through the list … I kept thinking about our own PSM’s (Panjabi Sikh Moms) … now now don’t think it’s funny to call our mummies’ PMS that actually stands for Panjabi Male Syndrome!

From corningware to marrying people off and stank eye … I found many similarities between KMs and PSMs (although the differences were stark … I don’t even think many PSMs know what redbean is let alone love it. And when it comes to Jesus … let’s just stick with the Gurus and Waheguruji)!

Inspired by Chiyo’s blog on Korean Moms, let’ start our own list of “Stuff Panjabi Sikh Moms’ Like”! I will begin …

- Tupperware (i.e. I am not just talkin’ about Rubbermaid … I mean sour cream and whipped butter dabhaa). Over time this Tupperware becomes yellow from all the haldhee in sabjis … but soak it in the sun and most of the stains go away. Slowly over time old ones are replaced as new ones are collected.

- Corningware (do I really need say anything more … I think Chiyo’s explanation resonates perfectly with PSMs).

- Zee TV, Sony TV, and Alpha Etc. Punjabi nateekhs (what’s your mom’s favorite soap opera …).

- Noon Dhani (i.e. the steel container with small steel bowls and spoons for all their spices).

- Dhahee (i.e. homemade yogurt … sorry I personally can’t stand the boxed stuff after growing up on my mom’s delicious freshly made dhahee).

- Outrage at the rising cost of Ataa (i.e. flour that is commonly bought at the Indian store to make roti).

- House-walls that are painted hospital white … look how clean and simple they look. The rooms feel much more lighted with this color.

- Overstuffing Family And Friends With Food … lai if they leave your house without a food-coma, they did not have a good-time.

- Cooking your favorite Panjabi dish when you come home from college. It’s a sign of how much she missed you.

- The ten Gurus’ pictures, particularly those of Guru Nanak Dev Ji and Guru Gobind Singh Ji, are the number one home-decorating items.

Please add to the list ( it’s in no particular order)! What do you think Panjabi Sikh Mom’s really like? I know many of you must have your own favorites! 🙂

Disclaimer: Please keep it clean, respectful, and hate-free … I really should not have to say this, but unfortunately in the virtual world people often display a “holds-no-bar” attitude when commenting on issues like this one.

This past week, I saw this advertisement about the “GurSikh Speed Meeting.” For those of you who have no idea the Sikhnet’s Gursikh Speed Meeting is obviously (and admittedly) the Sikh version of speed dating. According to the organizers of the program:

The concept is quite simple. An equal number of Sardars and Sardarnis register. On the event date, each Sardar will meet each Sardarni one-on-one and chat for a specified number of minutes rotating till they have met all the Singhnis. This face to face style of meeting has spurred much interest, in addition to, respecting the participant’s privacy. Only if there is an agreed ‘CLICK’ will an exchange of contact information occur.

I remember when I first saw Sikhnet advertising this a couple of years ago and thinking to myself, “this is bold.” I don’t necessarily think dating for Sikhs is anti-gurmat, but dating is definitely still taboo in A LOT of Punjabi Sikh families.

I remember going to Nagar Kirtans and being awed by those doing Gatka (i.e. Sikh martial arts)! Their “performances” were eye-catching with action, discipline, determination, and spirituality. Watching Gatka helped me connect with Sikh history at a time when there were little resources around me to learn about Sikhi. This martial art gave me some insight into the concept of a “saint-solider” – one who exemplifies Miri/Piri (spiritual/temporal power). I got to see how a saint-solider physically fought to defend Sikhi.

Lately, I have heard people ask, “Is Gatka a “performance” or a “martial art”? I think the “performance” part of the question comes from those who think Gatka is being done more to please crowds than spiritually connect with Sikhi. Also, some think Gatka techniques are being compromised in order for it to be more “safe” for crowd performances? I personally think, Gatka is both a performance and a marital art, but that does not mean spirituality or technique has to be compromised. What do others think?

A recent BBC show on Gatka addressed how it is becoming a way for Diasporic youth to connect to their Sikh heritage, while focusing on physical fitness. It also touches on non-Sikhs participating in Gatka. Let us know what you think!

p.s. I have always found it empowering to see Sikh girls participating in Gatka, even though I rarely see women on Gurdwara management committees!

Updated and extended, August 9

I try not to do this too often, but I realized I may not have adequately contextualized what I was getting at when posting on Hard Kaur. I’ve tried to extend the analysis and conversation below:

I’ve been thinking about Hard Kaur (Taran Kaur Dhillon) a lot lately, primarily because I’ve been flirting with the idea of buying her debut album, Supawoman. Hard Kaur is a tricky personality for me. On one hand, girlfriend has overcome the adversity of her hard knock life as a pioneer in her field. On the other hand, her conflation of Sikh and Punjabi identity, her often unimpressive rapping, and her totally not-Sikhi-friendly lyrics make me reconsider her as a role model. Is she an emblem for Sikh women’s empowerment, or perhaps just a symbol for women of color artists? Her moniker and image are dramatically at odds with one another. So what do we embrace, or eschew, from her, and can we negotiate how this works for young Sikh women?

Many point to HK’s intense image and claim that she is not a Sikh role-model, and others would claim she’s not a particularly good role model for other young women, either. I agree with the former and disagree with the latter (more after the jump).

In a recent post, Camille asked important questions around growing Sikh female leadership/representation, rather than just “managing” it. At the heart of leadership in any organization is decision-making. A critical component of growing Sikh female-leadership/representation is giving access to decision-making spaces that are commonly occupied by Sikh men and incorporating female perspectives into decision-making. Thus, you will see the strongest battles for gender equity in Sikh organizations tend to be fought around decision-making power. A recent example of such a battle was at a Gurdwara in Bristol, U.K. where two factions were fighting over allowing women to take part in Gurdwara elections. Women were demanding the right to vote while also running for committee-member seats. This past Sunday during Gurdwara management-committee elections, both factions broke out into a riot over allowing 79 women to vote past the registration deadline.

According to the Daily Mail:

Six riot vans were dispatched to close the road in Fishponds, Bristol, and one man was arrested and cautioned for a public order offence during the seven-hour stand-off.

Voting finally finished at 4pm and resulted in three women being voted onto the management committee for the first time in the temple’s history.

The trigger for the riot was when one man frustrated by the situation started trouble inside the Gurdwara that spilled out onto the street where “women were blocking his car and trying to push it over while he was still inside clinging to the steering wheel”.

An elderly women at the site reported “… a crowd of mainly women and children stood on one side of the road and men on the other. They were fronting each other up and shouting abuse across the road. The women were screaming ‘we’re not going anywhere’.

I was in London last week and stopped off in Hounslow, Ealing and Southall to just walk about and visit family. In the past 50 years, Southall has become a huge pass-through and historic cultural and political center for Punjabis, especially Indian and Sikh Punjabis, in London and the greater UK. I visited the neighborhood a few years ago, and I looked forward to returning.

I was in London last week and stopped off in Hounslow, Ealing and Southall to just walk about and visit family. In the past 50 years, Southall has become a huge pass-through and historic cultural and political center for Punjabis, especially Indian and Sikh Punjabis, in London and the greater UK. I visited the neighborhood a few years ago, and I looked forward to returning.

I was a little surprised to see that the neighborhood had changed. In addition to taking on an ever-growing refugee population from Somalia, there seemed to be a growing Sikh Punjabi underclass. Southall, historically, has been populated by working- and middle-class desis, and with that comes a variety of concerns around resource availability, support, language and social services, etc. Multi-family or multi-worker flats and apartments are not uncommon, but I was surprised by the increased concentration of subpar worker housing. Instead of the more prevalent norm of helping out new immigrants by sheltering them and helping them acclimate to London, there seemed to be a small (but growing) formation of Punjabi-run slum housing, similar to the exploitative workers’ ghettoes and communities of New York in the early- to mid-1900s.

I was really distressed by this development; Southall has amazing local institutions that are nationally and internationally reknowned for their civic engagement and dedication. In many ways, it is the face of the UK Sikh community, for better or worse. I’m not naive; I know that our community has deep and complicated internal issues and challenges. How do we begin to address these basic issues of justice, their connection to Sikhi, and what this means for the reputation and behavior of the community as a body? I don’t think we should dictate or micro-manage people’s behavior, but I do think it’s important to have begin to create ways to mediate conversations and norms/attitudes around how Sikh ethics translate into practice.