How do you know you’ve made it as a notable community? When Jeopardy! gives you your own category of clues… twice! That’s right, two nights ago my favorite game show featured the category “Punjab.” Because I can only remember three clues, those are the ones I’ll share:

100: After 1947, the territory known as the Punjab was divided between India and this country.

100: After 1947, the territory known as the Punjab was divided between India and this country.

400: This power fought two wars, unsuccessfully, before finally annexing the territory outright in the 1800s.

500: With origins in both Hinduism and Islam, this is the region’s major religion.

Now I’ll be honest, the last clue kind of had me cheesed (although, how nice is it that Sikhi is the “MVP” of the category?). This is one of the most misquoted “facts” that circulates regarding the origins of the Sikh religion — that it is somehow a hybridization of Hinduism and Islam. It’s certainly true that Sikhi developed in the context of at least two major religions, but many argue that it is somehow an extenuation or “compromise” of the two. So, at what level do we nitpick about the terminology used to describe the faith?

That said, there is a universality of messages across faiths. Both Hinduism and Sikhi discuss the value of “seva,” and both believe (broadly) in reincarnation. Meanwhile, Islam and Sikhi both conceptualize the writing of their scriptures as divine revelation, and both are monotheistic (and describe Allah, or Vaheguru, in similar terms). Like Buddhism, there is a belief that one must learn to free herself from the trappings of the material world, and like Christianity, there is a larger message of humanism and love for mankind. Is it really fair, then, to limit Sikhi’s philosophy to a “religion with its origins in Hinduism and Islam”? And, given Sikhi’s egalitarian acceptance of and respect for other faith traditions (or non-existence thereof), is such a battle on phrasing “worth it”?

I’m a bit of a stickler for language. While I’m not the most articulate person, I do feel that framing and terminology have power. I think it’s important to offer a coherent narrative that explains the difference between Sikhi and other faiths while making it clear that a delineation is not a derogation. There is nothing shameful in distinguishing Sikhi from other faith traditions; in this case, it’s an issue of accuracy and understanding.

A couple of months ago, maybe it was many weeks, I saw on the TV show, “Cops” with utter disgust a Bapuji and Biji, being a form of “entertainment” for a domestic violence assault. Along with my disgust, anger, and sorrow I had a “well yea it happens … you think it’s that shocking” attitude. I wasn’t “shaken” or “shocked” by the show because I knew this story was a reflection of what happens in many Punjabi Sikh homes in  thing again … what if Bibiji needs to leave him, permanently or just for a while, but has no family in the United States are close to the Central Valley where she may be working… where will she go? Plus, just the utter embarrassment she may feel because in their “budhaphaa” (i.e. older age) they are still facing this issue and she has to ask for help.

thing again … what if Bibiji needs to leave him, permanently or just for a while, but has no family in the United States are close to the Central Valley where she may be working… where will she go? Plus, just the utter embarrassment she may feel because in their “budhaphaa” (i.e. older age) they are still facing this issue and she has to ask for help.

I’m wondering what anti-domestic violence advocacy campaigns and shelters are doing to address the issues faced by elderly women. The advocacy and services they offer save lives and offer hope to help women escape a cycle of violence. It think they tend to be geared more towards meeting the needs of younger women and their children. They may not explicitly state that or have policies restricting elderly women from receiving their much-needed services, but I have a feeling younger women frequent them more often not because more younger women may face the issue of domestic violence or live in the Diaspora. I think it’s because elderly women may just be more hesitant to reach out for their services at their age. I wonder what services these women’s organizations have to meet the needs of elderly South Asian, specifically Punjabi Sikh, women who are primarily of immigrant background? The circumstances of elderly Punjabi Sikh women are similar but also very different compared to those who are younger. Factors leading to these differences range from length of marriage to having grandchildren as well as son and daughter-in-laws. The reasons and circumstances for immigration may be different as well. Some elderly couples immigrate, at times, to help build an economic base and

Any ideas about domestic abuse in South Asian elderly couples, specifically those of Punjabi Sikh background? How about available resources?

As I have been thinking about the Sikh community’s mobilization against post-9/11

I feel as though the discourse on Sikhs being the targets of racial profiling has really been about keshdari Sikhs. I must preface this argument with the statement that I understand the issues that khesdari Sikh men face every day are quite different than those of clean-shaven Sikhs. The experience of physically looking quite different than the majority of the clean-shaven population, regardless if it’s brown, white, yellow, or pink, that surrounds you does not make it “easy” to blend in. I sympathize and, more importantly, respect and admire your actions to keep your khes (i.e. hair) as a symbol of your Sikh identity. Furthermore, I undoubtedly agree that keshdari Sikhs have been the targets of racial profiling and victims of hate crimes following the events of 9/11 because “they look like Osama Bin Landen” and “all the other bad guys in

I have heard of a few cases of clean-shaven Punjabi Sikh men being racially profiled and harassed as our Arab and Muslim brothers … I would not doubt it happening to Latino men too. I remember one clean-shaven Punjabi Sikh gentlemen sharing his experience with racial profiling immediately following the 9/11 attacks in the film, “Divided We Fall: Americans In The Aftermath”. These stories made me wonder if Sikh organizations, such as the Sikh Coalition and SALDEF, have made a concerted effort to reach out to clean-shaven Punjabi Sikh men to document and represent their experiences in petitions and memos sent to policy makers and politicians about Sikh racial profiling. Or are these men not Sikh “enough” to be part of the discussion? Some could argue that it is the external representation of Sikh identity that is being targeted for racial profiling, such as the turban and beard; clean-shaven Sikh men don’t display either of those markers. However, I would argue, aren’t the majority of khesdari Sikh men being targeted because they are also “brown”? They are the ones I have commonly seen being represented in films, commercials, and literature on the fight against Sikh racial profiling. Hence, isn’t there a shared history of discrimination and profiling based on “dark” features” along with a common religious belief system, regardless of the varied decisions made by Punjabi Sikh men on keeping their hair?

Earlier this week the Haryana and Punjab high courts struck down a provision in SGPC-run schools that reserves 50% of its seats for Sikhs under the same concept as the federal provision for reserved seats for historic minorities. The SGPC is contesting the ruling, arguing that while Sikhs may constitute a majority of the Punjabi population, Amritdhari Sikhs, for whom seats are reserved, are a very small comparative minority.

This issue made me think of previous conversations I’ve had with friends over whether or not Amritdhari Sikhs, or even just Keshdari Sikhs, are a shrinking minority. Within the diaspora this is certainly the case — the number of Sikhs, particularly second- and third-genners, who choose to take amrit seems to decrease every year. I’ve met many folks who discuss their hesitancy; perhaps we don’t know Punjabi as well in the diaspora, or the lack of training within sangats makes it hard to pass on knowledge. But for many, being an Amritdhari Sikh also vastly limits their relationship choices and options.

As a community, do we see this as a problem? I always find this news disheartening, but I would be lying if I said I would line up to take amrit anytime soon. How does the growing expansion and changes of the demographics of the Sikh community make things easier, or more challenging, when it comes to advocating for issues together? Do different subsections of the population feel more or less lonely/alone in their experiences?

Blimey. Last week National Public Radio picked up a story about one of the newest scams to hit the community, that of Runaway Grooms. If NPR is doing a story about Punjabis and/or Sikhs, you’d hope it would be for something like this instead. So forgive me, if I think it’s disappointing (although maybe not surprising) that instead our community is the focus of an issue that seems to be quite prevalent in the Punjabi community in India and has links to England and North America aswell. Actually, it is very prevalent. Data suggests that 15,000 women in Punjab alone have been victim to men who, after getting married (and after taking the dowry money) return abroad never to be heard from again. Yup, these guys pull a Houdini. Here’s an excerpt from the NPR piece:

Blimey. Last week National Public Radio picked up a story about one of the newest scams to hit the community, that of Runaway Grooms. If NPR is doing a story about Punjabis and/or Sikhs, you’d hope it would be for something like this instead. So forgive me, if I think it’s disappointing (although maybe not surprising) that instead our community is the focus of an issue that seems to be quite prevalent in the Punjabi community in India and has links to England and North America aswell. Actually, it is very prevalent. Data suggests that 15,000 women in Punjab alone have been victim to men who, after getting married (and after taking the dowry money) return abroad never to be heard from again. Yup, these guys pull a Houdini. Here’s an excerpt from the NPR piece:

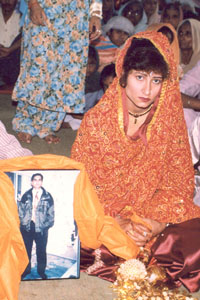

Satwant Kaur was full of hope and happiness on the day she got married. She had landed a husband who lived and worked overseas in Italy before returning to India to find a bride. She was looking forward to leaving her home in Punjab, northern India, for an exciting new life in Europe. Less than a week after the wedding, it became obvious that her husband, Sarwan Singh, had no intention of taking her with him back to Italy. She was the victim of a scam.

Women in India pay these men a hefty dowry in anticipation of the marriage and the promise to travel with them abroad. However, as it’s becoming increasingly clear, these men have NO intention of bringing their brides overseas and instead extort them of, what often is, their family’s savings. NPR may have picked this story up just recently, but this tale is not new. Ali Kazimi, a filmmaker, made a documentary about this called Runaway Grooms which has screened at various film festivals across the country. It’s a powerful film that leaves you in disbelief that this continues to happen in our community. What impacted me most about this film, however, was the strength that existed within these women who had quite clearly been abandoned. It reminded me of the same strength I see from Punjabi and Sikh women, that I know, who have come through similar tribulations.

At the root of this problem, and many others, is the tradition of daaj or dowry. Is this going away or has it’s form simply changed? I would suggest listening to the NPR piece and watching Runaway Grooms and then thinking about the impact this is having on our community. Our religion does not condone injustice, but more often than not, when those in our community are victims of fraud and lies, we always seem to look the other way…