We Sikhs are celebrating ‪‎Vaisakhi this week, the 315th birthday of the Khalsa, a body of revolutionaries given the responsibility to tear down tyranny and oppression in all its forms. Hundreds of years ago, Sikhs had an intersectional analysis of oppression, recognizing that all forms of injustice were equally deplorable, whether based on caste, gender, economic class, or religion. Unfortunately today, we don’t always live up to this important ideal as a community as we so often perpetuate one form of subjugation while attempting to challenge another.

The last few days, I have been re-reading a bunch of feminist writing on the ways all forms of oppression are deeply interlocked in preparation for a workshop I am facilitating next weekend. I have long been inspired by women of color and Third World feminism and suddenly realized how related this all is to Vaisakhi — a moment when our ancestors formalized their commitment to Sikhi, to bridging the spiritual and political, to becoming freedom fighters, to initiating the Khalsa.

What follows is a passage from Marilyn Frye’s timeless 1983 essay, “Oppression,” which I find especially compelling when thinking about the necessity of understanding and challenging all forms of domination. This Vaisakhi, I am thinking about how these words connect to our struggle and path as a Sikh community.

The experience of oppressed people is that the living of one’s life is confined and shaped by forces and barriers which are not accidental or occasional and hence avoidable, but are systematically related to each other in such a way as to catch one between and among them and restrict or penalize motion in any direction. It is the experience of being caged in: all avenues, in every direction, are blocked or booby trapped.

Cages. Consider a birdcage. If you look very closely at just one wire in the cage, you cannot see the other wires. If your conception of what is before you is determined by this myopic focus, you could look at that one wire, up and down the length of it, and be unable to see why a bird would not just fly around the wire any time it wanted to go somewhere. Furthermore, even if, one day at a time, you myopically inspected each wire, you still could not see why a bird would have trouble going past the wires to get anywhere. There is no physical property of any one wire, nothing that the closest scrutiny could discover, that will reveal how a bird could be inhibited or harmed by it except in the most accidental way. It is only when you step back, stop looking at the wires one by one, microscopically, and take a macroscopic view of the whole cage, that you can see why the bird does not go anywhere; and then you will see it in a moment. It will require no great subtlety of mental powers. It is perfectly obvious that the bird is surrounded by a network of systematically related barriers, no one of which would be the least hindrance to its flight, but which, by their relations to each other, are as confining as the solid walls of a dungeon.

A young Singh in the UK has been in the spotlight the last few days after his appearance on a dating television show called “Take Me Out.” I just heard about it a show on BBC Radio 1 hosted by Nihal, which you can listen to in its entirety here. Nihal speaks with Param, the dating show contestant, and takes comments from listeners, who discuss Param’s appearance on the show and more generally whether turban-wearing Sikh men are discriminated against when it comes to dating and marriage. As you’ll see in the clip below, as soon as Param comes out, 20 of the 30 women turn their lights off, indicating no interest in him. One woman who left her light on said she is interested in him because she could use Param’s turban to store her phone.

I recommend checking out Nihal’s discussion on the BBC especially starting at around 44:00 into the show if you don’t have time to listen to the whole thing. One caller named Jasminder asserts that when Param came down, it became more like a comedy show and less like a dating show given how the women and audience reacted. He continues that turban-wearing men often feel invisible to women, not literally, but “when it comes to actually going out with someone.”

“But, when you have a beard, a mustache, it’s like a mask. You can’t see the person’s face. It’s hidden.”

As disagreeable as the words sounded, my friend’s tone was very gentle and civil. It was almost as if he was asking me the question: why bother?

I was a nine-year-old Sikh boy with a little mustache fuzz and a patka (a Sikh boy’s headcovering), speaking with the clean-shaven teenaged Hindu boy next door whom I befriended on this extended trip to India. I would often play games with his younger brother, but with this older brother, our interaction usually took the form of conversations about our different cultures and religions.

His point about hair left me somewhat at a loss. I remember his facial expression after he made his statement – curiously waiting for a response that I would not have.

Later that evening, I presented this argument to my father. “He said people can’t see our true faces because of the hair on our face.”

My father didn’t take a second to respond. “This is my face”, he said very matter-of-factly, “this is how a man’s face naturally looks.”

The last few weeks, Sikhs around the world have been celebrating the anniversary of the birth of the Khalsa. I intended to do a Vaisakhi post earlier, but travels have kept me from sitting down and writing down some of my reflections until now. I have found myself in small and medium-sized towns throughout the midwestern and southern United States these last two weeks, feeling my outward identity as a Sikh projecting more conspicuously than ever.

NYC's Annual Sikh Day Parade

Consequently, I began thinking a lot about the significance of the Bana that Guru Gobind Singh gave us in 1699. What a fearless, defiant act of revolutionary love it was for Sikhs to wear their identity so visibly in a time when they faced such severe violent repression. A time when it was dangerous to be a Sikh, where being a Sikh meant you were an enemy of the empire, a threat, where there was a price on your head, a target on your back. Yet rather than blending into Indian society and building its movement for sovereignty and justice subversively, the Khalsa wore its identity loudly and proudly so everyone knew very clearly who a Sikh was.

I think about this today as more and more of cut our hair because we can’t take the torment of bullying in schools any more or trim our beards so we look more “professional” at our corporate jobs. Bana seems to have lost its appeal to many, for an ever-expanding list of reasons. Looking back at our history, it never has been easy. And perhaps that is part of the point. I wouldn’t wish the traumatic experience of racist harassment on anyone, but I know very well that I wouldn’t be the person I am today without all the struggles I have dealt with because of my Sikh identity.

Guest post by Naujawani Sardar

The title to this article might have conjured up images of a cowboy-style shoot ’em up between turban-donning, mounted riders, and whilst I would welcome development of such an idea into a film, sadly that’s not what i’m writing about. I am Sikh, Punjabi and Western (English) and like every other person growing up in the West I am challenged by the cultures of all three identities. I am also in my early thirties – if I think i’m having a tough time coming to terms with these uniforms, I am only thankful I am not ten years younger in the modern World.

Growing up in the West can be mentally taxing for young Sikhs. Whether English, American, Canadian or European, there pervades a Western notion of lifestyle, opportunity and prosperity that occasionally challenges the practices most of us engage in as Sikhs, and certainly impinges on the way we are brought up in Punjabi households. There is a wide array of ways in which the cultures denoted to us by birth clash with one another, from career choices to personal relationships, hairstyles to language usage. How we deal with these culture clashes will differ from individual to individual and whilst the maxim that a Sikh is a Sikh irrespective of their nationality, there is a growing need to support young people and help them to deal with life in a way that reflects the road they wish to travel on.

Young people find support from varied sources including friends, family, schools and independent organisations. The latter is what I would like to focus on seeing as this is the least regulated group from that list and arguably can have the most influence. In this context, independent organisations are extra-curricular clubs, societies and charities; places that provide essential skills in team-working, discipline and communication through playing a sport, learning a language or providing a service. Whilst engaging in an activity, young people are at least purportedly provided with guidance on everyday life and this is clearly seen in the confines of the Sikh experience: gatka akhare, Punjabi language classes, Khalsa/Gurdwara football teams, Sikh activist groups, and even online communities such as The Langar Hall.

Guest post by Nirbhau Kaur

[Admin note: This post was penned by the author the morning after election results were made public in Punjab.]

Pain. Disgust. Hurt. Dread. Longing. Connect, then Disconnect.

Pain. Disgust. Hurt. Dread. Longing. Connect, then Disconnect.

For the first time I felt these feelings in relation to Punjab – a land where I was not born, a land where I was not raised, a land that I didn’t truly experience until my early 20’s. Nonetheless, it is my father’s land, my Nana Ji’s land, my ancestors’ land. It is my land.

Today, there were countless social media updates reminding me of the five years of horror that Punjab is about to experience. For a small group of people, today was victorious. For a state full of people, today was just another reminder of their dark future. As the Badal family begins another five years of power in Punjab, the socially aware predict increased farmer suicides, increased drug and alcohol addictions, increased poverty. And the most grave prediction of them all, an end to Punjab, Punjabi, and Punjabiat.

Today, we express our disgust with the Badals and our sorrow for the future of Punjab. Not just today, but whenever there is an event to remember or increase awareness of any tragic situation in Punjab, be it farmer suicides or the despair in which the families of the shaheeds are surviving, we, as diasporic Punjabis, express deep sympathy. We speak of a need for change, we inspire, and we become inspired, but only in the appropriate setting. Shortly afterward, most of us move onto focus on our lives here, outside of Punjab.

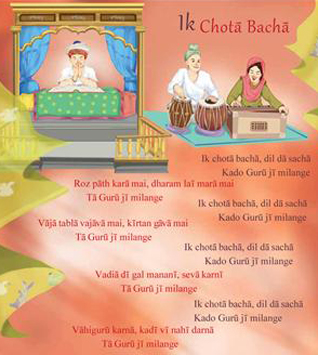

Embracing my new role as a proud Chacha, I recently bought some Sikhi-related children’s books for my niece for her first birthday. I was especially excited about this new book and CD of Sikh nursery rhymes called Ik Chota Bacha. The book/CD is a great way to teach basic Sikh values to kids and help develop their Punjabi skills (all the nursery rhymes are in Punjabi) in a fun way. I played the CD for my niece on the daily when I was visiting for her birthday, and by the end of the week, the whole family was singing along to some of the catchy (and rather cheesy) tunes. (See a full review of the book here.)

My excitement about the release Ik Chota Bacha quickly became muddied with disappointment and frustration once I saw the book’s illustrations. Every single Sikh child and adult depicted in the book looks WHITE. I don’t just mean they’re all fair-skinned on the spectrum of brownness. I mean peachy, rosey-cheeked, white.

Guest blogged by Gurchit Singh. Gurchit is a 16-year-old aspiring activist (in his own words) who submitted this piece (his first) to The Langar Hall. Raksha Bandan was last Saturday, August 13th.

Oh the joys of Raksha Bandan! The air is filled with love, family members are conversing and munching on a plethora of  sweets, hugs and kisses are being ecstatically extended to any and all family members the overemotional-mother can seem to get her loving arms around, and the overall mood in the home is one which many families can only dream of experiencing on a daily basis. Unfortunately, these loving moments only further promote a holiday which demotes women and opposes aspects of Sikhism itself.

sweets, hugs and kisses are being ecstatically extended to any and all family members the overemotional-mother can seem to get her loving arms around, and the overall mood in the home is one which many families can only dream of experiencing on a daily basis. Unfortunately, these loving moments only further promote a holiday which demotes women and opposes aspects of Sikhism itself.

While occupying myself with Facebook and sipping warm milk on the morning of Raksha Bandan, I was going through my daily routine of checking any notifications I may have received from the prior night. After reading many generic Raksha Bandan-related salutations, I finally came across one that actually defined what it was actually aimed at achieving: “Raksha Bandhan is a festival which celebrates the relationship between brothers and sisters. The ceremony involves the tying of a rakhi (sacred thread) by a sister on her brother’s wrist. This symbolizes the sister’s love and prayers for her brother’s well-being, and the brother’s lifelong vow to protect her.” While reading this definition, the two phrases that IMMEDIATELY jumped out at me were “sacred thread”, which conjured an instant connection to one of Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s earliest forms of rebellion against what he believed aimless and biased: the Janeu ( the full Sakhi can be referenced here), and “brother’s lifelong vow to protect her”, which called forth an image of a frail young woman constantly relying on her brother for protection from external occurrences.

Yes, we disagree. Yes, most of you even fight amongst yourselves. Our voices and opinions are as diverse as the people in our community. So be it. This is how we learn from one another.

Sometimes you challenge us (the bloggers). Most of the time you challenge each other (the commenters). Do I wish the level of discussion with each other could be raised? At times, yes. Do I appreciate that you take the time to engage? ABSOLUTELY! Why? Because you care enough about the community, about Gurbani, about our collective future to engage.

My childhood was full of insecurity and self-doubt, the result of years of harassment, taunts, and jokes about the ball/rag/tomato/towel/etc. on my head as a turban-wearing child. My insecurities, however, began to shift (or expand) as puberty hit. Let’s call it facial hair anxiety.

At first, having a moustache grow in at a young age wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. After all, I passed as much older than I was, which was nice for a scrawny brown kid like me.

But soon enough, the complex around my dhari (beard) settled in, and no amount of time with a thatha tied tightly  around my head was ever enough to totally alleviate my beard insecurities.

around my head was ever enough to totally alleviate my beard insecurities.

Surrounded by peers for whom shaving was a rite of passage into manhood, it’s not surprising that I felt a little left out (though to be clear, the idea of a razor on my face never sounded so pleasant). Further, I was inundated with the voices of young women in my school casually referring to facial hair as gross or unattractive (with no intention to hurt my feelings I’m sure) and their preference for guys who were “clean-shaven.”

CLEAN-shaven. The implication being that facial hair is…dirty?

These are the messages we get from our peers and from the media every day. So naturally I assumed it was highly unlikely that any of my female classmates would ever be interested in dating someone like me. The combination of a dirty face plus a patka was enough to cause a whole lot of anxiety and insecurity for this angsty teenage Singh.

According to Urban Dictionary (is there another source?), “The single most manly, and great thing a man can do [is grow a beard]. To have a beard is to be a true man. If you have a beard, show it off proudly, and enjoy the satisfaction of the envy in the eyes of people around you who don’t have beards. If you don’t have a beard, grow one.”

Well, that’s that. What could be a better way to start the weekend than a montage of beautiful beards and the rhymes of Jose Gonzalez?

A friend of the The Langar Hall and a Sikholar in her own right has started a fascinating website, called “Sikhs Wearing Things.”

A friend of the The Langar Hall and a Sikholar in her own right has started a fascinating website, called “Sikhs Wearing Things.”

The purpose of the blog states:

sikhs wearing things around the world.

inspired by the “muslims wearing things” tumblr. this is dedicated to showing a multiplicity of sikh styles in order to repudiate the notion of a single sikh identity.

And is dedicated to her late father, a very stylish Sikh.

The goals of the site is largely in keeping with our own vision of The Langar Hall – where there is no single Sikh opinion and the Langar Hall on-line or in-life is the place where a diversity of views and ideas can be shared, debated, and considered.

Check out the site and maybe even send the blogger some of your own thoughts and pictures!

Guest blogged by Preeti Kaur. Preeti wrote this poem for The Langar Hall in commemoration of the 312th anniversary of the birth of the Khalsa this week.

Vaisakhi

i’ve never seen a wheat harvest

never worried over winter punjab frost

monsanto seed or otherwise grown into grain

carried tender on the heads of women

to grind into a thousand rotis to feed the family

i’ve never seen jallianwala bagh

garden of colonial blood bullet 400+ bodies

a small boy at the bottom of the well the only hope left alive

the patka on his head a flag

our flag

i’ve never seen 13 Singhs standing

their blood the ink to keep the record straight

holy is the water which sheds from the mothers’ eyes

began with the first bullet into the belly of amritsar’s shaheeds

ended with flaming tires around dastars in delhi

or never ended at all

perhaps

i’ve never seen

i’ve never seen

all i’ve seen a phulkari of gulabi firozi

turban tractors atop john deere

sift california san joaquin valley silt

almonds pistachios raisins oh my

i’ve seen saag paneer packaged spacefood

five dollars on the TJ grocery store shelf

i’ve seen gossip fly continents

aunty-to-aunty gupshupper network to chacha’s pateeja to you-know-who to me to you

i’ve seen lines of taxis at the san fran airport

spot the pagg to pick up my overstuffed luggage

drive me home

jugni jaa vari umreeka

(more…)

Image: Copyright Saffron Press

As a very proud Masi, I often find myself wondering how we can make events such as Vaisakhi, more meaningful for the next generation. Why is it that we exchange cards and gifts during Christmas, and yet for Vaisakhi, a Facebook status update suffices? While I fully support children exploring and participating in global celebrations, I think it is just as important (perhaps more so) that Sikh children are raised celebrating Vaisakhi in a similarly joyful way. For Sikhs living in the diaspora, Vaisakhi is often associated with nagar kirtans, melas, and gurdwara visits. This is a great way for children to celebrate the occasion with the community, however, I am not sure the event really resonates with them.

For example, did you know about the significance of kite flying during Vaisakhi?

The spring air of Vaisakh makes kite flying a popular pass time. A kite is called a Patang or Guddi Manjha in Panjab. The wood and bamboo roll on which the string is wound is called a Charkhadi. Children often give their kites a special name to reflect their personal designs such as: Pari (fairy), Chand Mama (man-in-the-moon/uncle moon), Shakkar Para (a panjabi sweet). Poetry may also be written in Panjabi on the Patang to send messages to a special person up on the roof. [link]

How fun would it be to have kite flying events for Sikh children? They could invite their non-Sikh friends and use it as a way to share their heritage. Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s important not to commercialize historical occasions – however, we have to be willing to celebrate our history so that it is meaningful. So I’m curious – what does Vaisakhi mean to you and how do you celebrate it? How would you like your children, your nieces or nephews to remember Vaisakhi? Or if you are a parent, how do you make Vaisakhi meaningful for your children?

Here is a useful document for parents and educators, describing ways to celebrate Vaisakhi with children. Happy Vaisakhi!

Guest blogged by santokh

A couple days ago I was reading some news articles on Hondh Chillar and Pataudi. Some of these articles include photographs from the two big events that took place at Hondh Chillar–clean up of the destroyed gurdwara building and Akhand Paath that took place thereafter in that building. I was talking to a couple friends about what all of this means for us as Sikhs, as youth with a vested interested in all things Punjab but separated from it by distance, and as a generation that, despite a fascination and infatuation with Punjab and Sikhi, seems disconnected to the memory of 1984 in many ways.

I was born a year after Operation Bluestar, no one from my family or relatives were directly affected by the genocide, my grandparents didn’t live close to New Delhi, Amritsar, or any of the other affected areas–Hondh Chillar and Pataudi, for example. As I was talking with my friends, I realized our awareness of Bluestar comes from websites, media, press releases by advocacy groups, a few books and essays, and the occasional speech at gurdwara or elsewhere almost as an annual ritual in June and November. It’s almost a kind of dynamic I can chart out–come the first week of June and November, emotions run high and my inbox is filled with invites to a number of vigils and memorials.

If I view the memory of Bluestar from the perspective of a generation before mine, everything changes. Many of my friends’ parents and grandparents were directly affected in 1984 as victims and/or witnesses. They have a direct connection to and memory of Bluestar. They know what media channels did and did not report, each of them is a walking memorial in a sense.

There was an interesting whimsical read in the Wall Street Journal by a Yale Law Professor, titled “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior” The article states that the ethnicity has some possible substitutions, so I indulged, as its main opposition is suppose to be something called “Western.”

There was an interesting whimsical read in the Wall Street Journal by a Yale Law Professor, titled “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior” The article states that the ethnicity has some possible substitutions, so I indulged, as its main opposition is suppose to be something called “Western.”

Here are some of its insights:

A lot of people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids. They wonder what these parents do to produce so many math whizzes and music prodigies, what it’s like inside the family, and whether they could do it too. Well, I can tell them, because I’ve done it. Here are some things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do:

- attend a sleepover

- have a playdate

- be in a school play

- complain about not being in a school play

- watch TV or play computer games

- choose their own extracurricular activities

- get any grade less than an A

- not be the No. 1 student in every subject except gym and drama

- play any instrument other than the piano or violin

- not play the piano or violin.

For more discussion, click below the fold

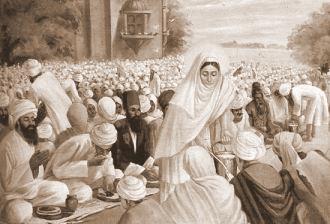

The concept of langar is probably one of the most unique aspects of the Sikh faith. For hundreds of years now, Sikhs have carried on this tradition which was first started by Guru Nanak Dev Ji and later institutionalized by Guru Amar Das Ji. W.O. Cole, who studies Sikhi, states “…, the unique concept of universality and the system of Langar (free community meal) in Sikhism are the two features that attract me towards the study of Sikhism. Langar is the exclusive feature of Sikhism and found nowhere else in the world.”

The concept of langar is probably one of the most unique aspects of the Sikh faith. For hundreds of years now, Sikhs have carried on this tradition which was first started by Guru Nanak Dev Ji and later institutionalized by Guru Amar Das Ji. W.O. Cole, who studies Sikhi, states “…, the unique concept of universality and the system of Langar (free community meal) in Sikhism are the two features that attract me towards the study of Sikhism. Langar is the exclusive feature of Sikhism and found nowhere else in the world.”

There are essentially two elements of langar. One is clear in its definition of free kitchen and the tradition of expressing the ethics of sharing, community, inclusiveness and oneness of all humankind. The second element is that langar should be simple. The cost of langar is covered by voluntary donations from the sangat and is made through the hands of seva.

Today, langar has transformed into (as some people joke) “the dollar buffet.” I don’t find this joke to be amusing at all. Everytime I go into a gurdwara now, I am overloaded by the amount of food which is made (and often times wasted). Langar was meant to be simple – probably so that we could feed the most amount of people in the most efficient manner. Everyone wants their langar to be the most complimented and delicious meal but too often we forget that is not the intention.

We want the sangat to participate in langar seva and we want them to be able to afford to do so. Let’s not add the adverse health impact of food we serve in gurdwaras today to this equation. If our standard today is that langar should include lavish spreads at breakfast time and lunch time, I am not surprised why gurdwaras need to constantly ask the sangat to please do langar seva. Let’s keep the costs down and encourage the making of simple langars and this way, all community members (not just middle and upper class Sikhs) have an opportunity to do this seva.

An interesting read on the Sociology of Langar can be found here.

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage month (APAHM), celebrating the contributions of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the US. [link] Hopefully your schools, employers or communities have been celebrating. The White House joined in the celebration recently and Sikhs got a mention.

“We draw strength from the rich tradition that everybody can call America home because we all came from somewhere else except for the first Americans. “E pluribus unum.” Out of many, one. And there’s no better example of this than the communities that are represented in this room,” Obama said. “Your role in America’s story has not always been given its due. Many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have known tremendous unfairness and injustice during our history,” Obama said. The US President said generations of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders helped to build this country, defend this country, and make America what it is today… “And for this reason, we are here today to celebrate these contributions. But we’re also holding this event because I want to make sure that we are hearing from you so that the government does its part on your behalf, just as you’re doing your part on America’s behalf,” he said. “That’s why we’re always welcoming your input: from meetings with Sikh Americans to Native Hawaiians. [link]

Enjoy the rest of the celebrations!

I saw this on the New York Times right now and just thought I would share a nice story. If you get a chance, go watch the video. Congratulations Sona and Justin!

I saw this on the New York Times right now and just thought I would share a nice story. If you get a chance, go watch the video. Congratulations Sona and Justin!

Guest blogged by Ajj Kaim

Two of my friends invited me to a Holi party in San Francisco last Friday(03/05/10). They told me the DJ was great and he always played awesome Bollywood/Bhangra music. Being an ardent dance lover this was enough motivation for me to say yes. The venue of the party was Supperclub, which seemed a lot different from any other club that I have been to. Once I was at the venue I found out that the event was organized by Asha (organization which promotes education of underpreviliged children in India) and Trikone (non-profit organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people of South Asian descent) .

Over the past several months I have been accustomed to the crowd at Rikshaw Stop for Non Stop Bhangra party every month so this atmosphere was a lot different for me. The DJ kick started the evening with a good mix of Bhangra and Bollywood music. The regular flow of the party was disrupted by two “artists” who tried to entertain the crowd with tasteless mix of bollywood dance, vulgarity and modern art. I had a hard time understanding what was being appreciated by some of the on-lookers. This break lasted for about 10 minutes and after that DJ Precaution started belting some more amazing tracks. It seemed like a perfect way to unwind after a hectic week at work. And then this happened.