Beginning on October 15th, a three-day exhibition was held in Ludhiana to profile a generation of rising young artists in Punjab. The mission according to gallery is ‘to further enrich and diversify cultural life in the Punjab region by facilitating the development of emerging artists.’ The newly constructed gallery in Ludhiana offers exhibition and installation space, leads and collaborates in the development of programs for the visual and performing arts, and will soon be providing an art residency.

A recent exhibit called ‘Three/One: A Collaborative Art Exhibition in Ludhiana’ was held to showcase the work of Rachna Sidhu, Ankur Singh Patar, and Vivek Pandher, children of some of the most famous literary figures in Punjab. Rachna Sidhu, daughter of the famous thinker and literary critic Amarjit Grewal is a portrait maker at Guru Nanak International public school. Vivek Pandher is the son of the poetic genius Jaswant Zafar, a photographer by profession and a student of film production at UBC. Finally Ankur Singh Patar is son of poetic legend Surjit Patar and focuses on digital art, drawing much of his inspiration from his father’s literary treasures.

A recent exhibit called ‘Three/One: A Collaborative Art Exhibition in Ludhiana’ was held to showcase the work of Rachna Sidhu, Ankur Singh Patar, and Vivek Pandher, children of some of the most famous literary figures in Punjab. Rachna Sidhu, daughter of the famous thinker and literary critic Amarjit Grewal is a portrait maker at Guru Nanak International public school. Vivek Pandher is the son of the poetic genius Jaswant Zafar, a photographer by profession and a student of film production at UBC. Finally Ankur Singh Patar is son of poetic legend Surjit Patar and focuses on digital art, drawing much of his inspiration from his father’s literary treasures.

Guest blogged by Satvinder Kaur Dhaliwal

Admin Note: After completing her undergraduate studies in Anthropology, the author traveled to Panjab to volunteer. She spent her time volunteering at Pingalwara and working with the Baba Nanak Education Society (BNES). Below is an article she wrote for BNES to raise awareness about their impactful work addressing farmer suicides.

::

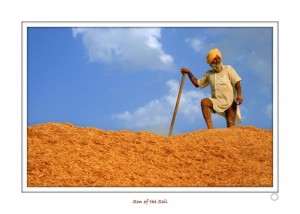

Village Barlan, District Sangrur, located near the Panjab-Haryana border, depicts the prosperous, joyful Panjab that many of us are eager to visit. Roads leading to the village are surrounded by what appearsto be flourishing farmland, stretching as far as one can see. Children have returned from school and are laughing and chasing each other through the streets of the village, the elderly have gathered to discuss recent happenings, and women can be seen carrying various necessities to their homes. This first glance overview of Balran disguises a harsh reality that a growing number of households in the village are facing – suicide.

Suicide is an equal opportunity visitor in Balran and many other villages throughout Panjab. Increasing farming costs, the removal of farmers’ subsidies, and low rates for crops are putting Panjab’s farmers in a never-ending cycle of debt accumulation. Each year, farmers in Panjab face increased agricultural costs and low returns for their crops. In order to cover these costs, farmers must take out loans, which they usually get from their local aarthiya or money-lender. The aarthiya often ends up being the same individual who will buy the farmer’s crop at the mandi or market, and then re-sell the crop on the public market. Sukhjinder Singh, a farmer, described the reason for debt accumulation as, “Let’s say that I sell my crop for 11 rupees per kilogram. When I need to purchase the same crop for my home, I have to buy it for 14 rupees per kilogram. So how can we profit?” Consequently, when a farmer’s costs are constantly exceeding his profits, he must cover his costs by taking out loans. Now, he has increased his debt by introducing extremely high interest rates, which are often decided by the aarthiya.

Unlike the west, the gendered demarcations of males and females in Panjab are much more stark, and it is common for women to be unaware of their family’s financial circumstances. Therefore, when the male becomes consumed in debt and can no longer bear humiliation from the taunting money-lenders, he begins to see only one way out – suicide. His surviving family members are not only left devastated, but they must find a way to provide for themselves and pay off the debt on their family, of which they may never have been aware in the first place. Often times the surviving family members include a wife, children, and elderly parents. In winter 2011, I visited the families of various suicide victims in Balran. Some families had lost their loved one a few years ago, while some had only experienced the loss a few days ago. Although I only visited seven families, the Baba Nanak Education Society has documented 91 suicides and numerous missing individuals in Balran since 1998. Nonetheless, all family members were still grieving equally and struggling to pay off their debt.

Bleak is all I can say!

Some posts require a soundtrack – click on the following to play along as you read.

Last week, Raja Parkash Badal crowned his son, the young prince, the new Deputy Chief Minister of Punjab. In a move unprecedented even in the nepotistic land that is India, Parkash Singh Badal coronated his son. Maybe it shouldn’t be so surprising in the land of five rivers, where Badal Senior had already elevated his family members to 5 of the top 18 cabinet seats.

In an effort to better understand the food habitats of Panjabi immigrants, Canadian researchers conducted a three-year study on the ingredients used in daily Panjabi meals and food choices made by Panjabi families.

Gwen Chapman, study leader and British Columbia University nutrition professor, stated:

“Since cardiovascular diseases and type II diabetes are more prevalent among Indians and they are linked to food habits, we wanted to understand what ingredients went into daily Punjabi or Indian meals.”

An important part of study was also understanding how cultural affiliations play a role in Panjabi immigrant food choices.

Researchers found that “in Punjabi families in British Columbia … separate meals are often prepared to accommodate elders who need traditional roti, daal and subji, and younger family members who prefer to balance Indian and “Canadian” foods.”

While reading this article I thought about how these food choices actually play out in immigrant Panjabi homes across North America. I remember the rotis without butter for those who have high cholesterol and the weekend meal of burger and fries for us “American” kids. There were also the interesting “masalaa” pastas, lasagnas, and pizzas that had a “Panjabi” twist (i.e. tons of garam-masalaa). I recall uncles’ refusing to eat “kaa-foos” prepared by their wives, aunties making tofu-sabiji, and mothers’ substituting olive oil for vegetable oil when making tarkas. Many of these food choices were an effort to provide more healthy meals as a “preventive” form of action against heart disease and diabetes; while others were made to satisfy taste-buds.

So I was wondering what interesting food choices have you seen Panjabi families make in the Diaspora both to satisfy taste-buds and become more healthy?

So recently I came across a blog about all the “Stuff Korean Moms Like”. A Korean girl, Chiyo, who loves her KM (Korean Mom) decided to create this blog “to share the joy and dread of KM”. As I went through the list … I kept thinking about our own PSM’s (Panjabi Sikh Moms) … now now don’t think it’s funny to call our mummies’ PMS that actually stands for Panjabi Male Syndrome!

As I went through the list … I kept thinking about our own PSM’s (Panjabi Sikh Moms) … now now don’t think it’s funny to call our mummies’ PMS that actually stands for Panjabi Male Syndrome!

From corningware to marrying people off and stank eye … I found many similarities between KMs and PSMs (although the differences were stark … I don’t even think many PSMs know what redbean is let alone love it. And when it comes to Jesus … let’s just stick with the Gurus and Waheguruji)!

Inspired by Chiyo’s blog on Korean Moms, let’ start our own list of “Stuff Panjabi Sikh Moms’ Like”! I will begin …

- Tupperware (i.e. I am not just talkin’ about Rubbermaid … I mean sour cream and whipped butter dabhaa). Over time this Tupperware becomes yellow from all the haldhee in sabjis … but soak it in the sun and most of the stains go away. Slowly over time old ones are replaced as new ones are collected.

- Corningware (do I really need say anything more … I think Chiyo’s explanation resonates perfectly with PSMs).

- Zee TV, Sony TV, and Alpha Etc. Punjabi nateekhs (what’s your mom’s favorite soap opera …).

- Noon Dhani (i.e. the steel container with small steel bowls and spoons for all their spices).

- Dhahee (i.e. homemade yogurt … sorry I personally can’t stand the boxed stuff after growing up on my mom’s delicious freshly made dhahee).

- Outrage at the rising cost of Ataa (i.e. flour that is commonly bought at the Indian store to make roti).

- House-walls that are painted hospital white … look how clean and simple they look. The rooms feel much more lighted with this color.

- Overstuffing Family And Friends With Food … lai if they leave your house without a food-coma, they did not have a good-time.

- Cooking your favorite Panjabi dish when you come home from college. It’s a sign of how much she missed you.

- The ten Gurus’ pictures, particularly those of Guru Nanak Dev Ji and Guru Gobind Singh Ji, are the number one home-decorating items.

Please add to the list ( it’s in no particular order)! What do you think Panjabi Sikh Mom’s really like? I know many of you must have your own favorites!

Disclaimer: Please keep it clean, respectful, and hate-free … I really should not have to say this, but unfortunately in the virtual world people often display a “holds-no-bar” attitude when commenting on issues like this one.

From 7-Elevens to liquor and 99 cents stores, many Panjabi Sikh immigrants build a life for themselves as store workers. Working at these locations gives them a start in America, while engaging with its harsh realities. Regardless of educational background or the pind/shari divide, Panjabi Sikh immigrants work long hours into the night seven days of week trying to build a stable economic future for them and their families. On August 04, 2008, Inderjit Singh Jassal at the age of 62, was one of these Panjabi Sikh immigrants, who was murdered at a 7-11 store during his usual 13-hour shift in Phoenix, Arizona. Jassal had moved to the US nearly 20 years ago, while his wife and two adult children remained in India.

SALDEF reports that:

Mr. Jassal was working at a 7-11 store in West Phoenix when a black male, later identified as 27 year-old Jermaine Canada, walked in with his two children, aged 2 and 6. According to the surveillance video, the two individuals had a short conversation, at the end of which Mr. Canada pulled a concealed firearm from his shirt and fatally shot Mr. Jassal.

The most ironic aspect of this case is that no motive as been found. According to surveillance video there was no angry exchange between Jassal and Canada and nothing was stolen by the murderer.

SALDEF believes that this killing was nothing other than “… a heinous crime motivated by hate”.

According to one of Canada’s relatives, he had a history of drug abuse and mental illness. At the time of the killing, he was under supervised release following 2 years in prison for violating his probation, for a prior dug conviction, with a weapons charge.

Currently, Tajinder Singh Jassal, a nephew of Inderjit Singh Jassal and co-worker, is working to get immigration visas for Inderjit’s wife and children. He is considering sending an appeal letter to Arizona Senator John McCain’s Office for assistance with the visas because “The family is suffering right now. They want to see their father’s face.”

Langa(w)riters have posted in the past on issues surrounding the preservation of the Panjabi language here, here, and here. Be it anywhere from Panjab to North America, the preservation of the Panjabi language is intimately tied to the preservation of a Panjabi and Sikh heritage. For example, in a recent article on Live Oaks High School offering Panjabi courses, Mohinder Singh Ghag, director of Live Oaks Schools Foundation stated:

“The language is the only reason we have a link to our ancestors.”

Thus, the discussion around solutions has understandably centered around learning Panjabi in homes, gurdwaras, high schools and universities. I personally think having these learning opportunities available at all these different sites is a much-needed step towards maintaining the Panjabi language. I have always found the process of getting Panjabi classes taught in high schools particularly interesting because of how they require engaging the community, the reasons for creating them, and how they are incorporated into the public K-12 educational system.

For example, commendably in Live Oaks, California (located about 10 miles north of Yuba City, California):

Punjabi community members knocked on doors and made announcements in temples to get teenagers to sign a petition expressing interest in a Punjabi language class at Live Oak High School.

About 25 students signed-up.

So this week, I blogged about two unfortunate murders in the community. Maybe as a release, maybe just to cheer everyone up for the weekend, I am returning to my Friday lite post.

We’ve seen the talent in Britain, with Suleman Mirza and Madhu Singh together as Signature. And as brilliant as they may be, I have a partiality towards Sardool Sikandar.

Sardool Sikandar is often known more for his marriage to the beautiful Amar Noorie than for his own singing talent. However, hits like Tor Punjaban Di and Mittran Nu Margiya still remain some of my favorites.

Here is a recording from the mid 1980s at Doordarshan’s Amritsar studios. It was this performance that launched the Sufiana classically-trained Sikandar’s career. Here he does various impressions of Mohammad Siddique and Ranjit Kaur’s classic “Aagay Roadways di lari, na koi sheesha na koi bari….”

While I am partial to his amazing Kuldip Manak and Yamla Jatt, do you have a favorite?

I recently read an article by Christine Moliner, a French doctoral student in anthropology. The article’s title “Frères ennemis? Relations between Panjabi Sikhs and Muslims in the Diaspora” caught my attention and I thought it raised a number of interesting questions. While the different issues raised in the article may be of note, one that was most prominent for me is the romantic project to which I have also been delusional. It is the romance that is Panjabiyat.

Moliner aptly defines it:

Within this large South Asian category there co-exist several narrower types of identification that nonetheless cut across the national/religious divide. One of the most powerful ones is Panjabyat. This term of recent coinage, roughly translated as Panjabi identity, refers to the cultural heritage, the social practices, the values shared by all Panjabis, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, Indians, Pakistanis, and increasingly the diaspora. It is heavily loaded with nostalgia for pre-partition undivided Panjab, idealized as a unique space of communal harmony. Its usage tends to be restricted to intellectual, literary, academic or media circles, and although these valorize popular culture in their definition of Panjabyat, the term is not much used by the people. [Emphasis added]

Guest blogged by Bandana Kaur

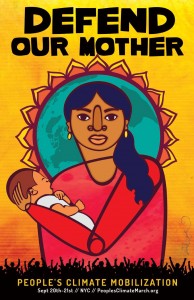

“Pavan guru paanee pitaa

Maataa dharat mahat

Divas raat du-i daa-ee daayaa

Khaylai sagal jagat”

-Guru Nanak SahibÂ

In honor of the Sikh concern for preserving ‘Mata Dharat’ (Mother Earth), Sikhs from cities across the northeast are joining the People’s Climate March in New York City on September 21st, the largest mass movement for climate justice in history.

Next week, world leaders are coming to New York City for a UN summit on the climate crisis. The world is urging governments to support an ambitious global agreement to dramatically reduce global warming pollution.

With our future on the line and the whole world watching, we’ll take a stand to bend the course of history. We’ll take to the streets to demand the world we know is within our reach: a world with an economy that works for people and the planet; a world safe from the ravages of climate change; a world with good jobs, clean air and water, and healthy communities.

Why Are We Marching?

We march because Sikhi affirms the sanctity of the Earth.

We march because the ecological basis of Sikhi rests in the understanding that the Creator (‘Qadir’) and the Creation (‘Qudrat’) are One. The Divine permeates all life, and is inherent in the manifest creation around us, from the wind that blows across land and skies, to the water that flows through rivers and seas, to the forests and fields and all creatures of land and sea that depend on the earth for sustenance.

We march because Sikh Gurus teach that there is no duality between the force which makes a flower grow and the petals we are able to touch and sense with our fingers.

We march because the Sikh Gurus referred to the Earth as a ‘Dharamsaal,’ a place where union with the Divine is attained. Guru Nanak describes this in Jap Sahib, that amid the rhythms of Creation, the changing seasons, air, and water, the Creator established the earth as the home for humans to realize their Divinity in this world.

There are only a few days left in the annual SikhNet Youth Online Film Festival. Â This year’s theme, “onKaur: Focusing the Lens on Women”, brings together a collection of 18 films by and about Sikh women. Â The films look at the idea of “Kaur”, what that means and how it can be represented in film.

There are only a few days left in the annual SikhNet Youth Online Film Festival. Â This year’s theme, “onKaur: Focusing the Lens on Women”, brings together a collection of 18 films by and about Sikh women. Â The films look at the idea of “Kaur”, what that means and how it can be represented in film.

The films have been categorized as documentary (“think”) and drama (“cry”) with issues including: Anand Karaj, bullying, hair, health issues of Panjab, gender justice, family, and gatka among others.

The film festival is important for several reasons and this year’s theme brings to light the need to include Sikh women’s voices in conversations around identity and community. Â It’s a valuable way of showcasing issues affecting Sikh women.

Here’s how to view and vote:

The film festival also provides a platform for young filmmakers to showcase their films to a wider audience.

1. View the documentary films here and vote via Facebook.

2. View the drama films here and vote via Facebook.

Voting ends on October 9th.

Co-blogged by Sundari and The Sikh Love Stories Project

Each year, International Women’s Day is celebrated to honor women’s economic, political and social achievements. As individuals around the world celebrate this day – in both big ways and small – I am left to consider how we can work to honor the achievements of Sikh women not only today but on an ongoing basis.  Sikh women have contributed in such meaningful ways, and yet much of that dialogue is often missing from our history.

In this post, we will be sharing some images with you and discuss various ways Sikh women have been witness to and engaged in our history both locally and globally.  We know this post will not be comprehensive – there is much to unearth about Sikh women’s contributions – but we hope it’s a starting point that will encourage us to keep this valuable history in our minds. Many of the following images each depict a different element of Sikh women in history.

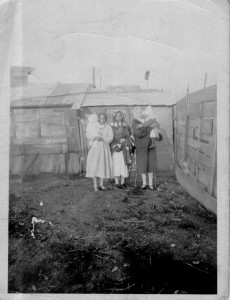

Stories often begin with immigration and this first image shows Sikh women pioneers in Canada who were part of an immigrant labor force recruited in the early years of the twentieth century.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Canada’s largest mill community, Fraser Mills in New Westminster, BC, had between 200 and 300 Sikhs living and working there in 1925.

In this photograph from that period, three Sikh women stand in front of company houses at the mill. [link]

One of them wears a traditional embroidered shawl called ‘phulkari’. The phulkari played an important role in the lifecycle rituals of women in Punjabi villages at times of birth, marriage and death.

Guest blogged by Santbir Singh

I try to imagine the government coming to my house one morning and taking my five year old daughter and eight year old son away to a boarding school hundreds of kilometres away. I try to imagine that at this school, my children’s hair will be cut, their dastars and kakkars will be removed and they will be forcibly baptized as Christians. I try to imagine that they will be beaten for speaking Panjabi, reading Bani or trying to maintain their religious and cultural traditions. I try to imagine that even their basic health needs will not be looked after and they may well die from treatable infections and diseases. And then, I must admit, I am not able to imagine the rest; I can not bear to imagine them being abused, assaulted, beaten and raped.

That is what occurred in this country for one hundred years as the Canadian government, along with government sanctioned church groups, kidnapped First Nations children from their homes and took them to residential schools where unspeakable horrors were committed on them. Of course the history of colonization in the Americas does not begin with the Residential School system but is in fact a legacy going back centuries. It is estimated that 90 to 95% of all indigenous people living in the Americas were killed by smallpox within the first century after European first contact in the late 1400’s. It is difficult to fathom death at that scale. Those that remained had their land stolen and were forced onto reservations to live as non-citizens in their own lands.

As a nation, Sikhs are extremely proud of our own anti-colonial struggle against the British. Yet we have completely failed to acknowledge that in Canada we have succeeded due to the colonial oppression of other nations. This land where we build our homes and businesses was the land of nations that lived here for tens of thousands of years. Yes, one hundred and seventy years ago the British annexed Panjab and ended Khalsa Raj. But the British did not exile us from our own villages and towns. The British did not take our land and build new cities. The British did not migrate to Panjab and force us to live on inadequate reserves.

In a recent piece on BBC Radio 4, titled Beyond Belief – Women in Sikhism, host Ernie Rea starts off with this statement,

“The Sikh religion is the world’s fifth largest… the men are often easily recognized – they wear turbans and leave their hair uncut. Â The fundamental message appears to be simple – God is one and all people are equal. Â But are some more equal than others? Â If the Sikh scriptures are consistent with a feminist agenda, why do some Sikh women feel like they are second class citizens?”

The host is joined by a panel of three women to discuss the issue of equality within the Sikh faith – Navtej Purewal, Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences at Manchester University; Eleanor Nesbitt, Professor Emeritus at the Institute of Education in the University of Warwick; and Nicky Guninder Kaur Singh, Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Colby College.  The panelists did a great job of explaining what in fact Sikh scriptures say about equality and the role of women.  In addition, they helped identify the gaps that still exist between what is written and how it is practiced.  While these women speak predominately from an academic standpoint and not necessarily the community Sikh women’s voice, i think they brought forth a much important discussion for our community as a whole.  It was also quite eye-opening to hear the non-Sikh perception of our faith, represented by the host.

While parts of the conversation – often guided by host Ernie Rea – landed on discussions around topics that are common to this blog, (i.e. if Sikhi believes in equality, why does Panjab have the highest rates of female foeticide and if Sikhi is an egalitarian faith, why do men and women sit separately within the Gurdwara), the overall discussion was helpful as it raised questions that need to be addressed if changes are going to be made. Â The host began by asking whether or not the Sikh scripture does include a feminist agenda.

Purewal noted that the the Guru Granth Sahib was very revolutionary and, as far as doctrine, it does have the potential to be feminist.  However, due to social convention the message has not been actualized among Sikh communities, whether in India or within the diaspora.  Nesbitt suggested that since the scripture is predominately written in poetry, it is thus open to interpretation and that this is potentially the cause for much of the tensions felt by contemporary women.  Singh goes on to say that even the word “God” brings forth the notion of a male entity which is a starting point for many misconceptions and in fact, in the Guru Granth Sahib Ik Onkaar does speak to being gender-free.

This weekend, from Friday to Sunday October 19-21st, the Sikh Studies department at Hofstra University will host ‘Sikhi(sm), Literature and Film,’ a conference on literary and visual cultures in the Sikh tradition, both in Panjab and the Diaspora.

Paper presentations will be given during five sessions, with presentations ranging from de-categorizing the janamsakhis to the poetry of Puran Singh, discourses on secularism to literary representations of Sikhs, Sikh masculine identity vis-à-vis kesh and the dastaar to Panjabi theater, Museum exhibitions to Sikh identity in film and Bollywood, Hip Hop and rap as expressive forms among Panjabi youth to Gurbani sangeet and female kirtaniya. Presentation topics and bios can be accessed via the Sikh Studies website at Hofstra.

Paper presentations will be given during five sessions, with presentations ranging from de-categorizing the janamsakhis to the poetry of Puran Singh, discourses on secularism to literary representations of Sikhs, Sikh masculine identity vis-à-vis kesh and the dastaar to Panjabi theater, Museum exhibitions to Sikh identity in film and Bollywood, Hip Hop and rap as expressive forms among Panjabi youth to Gurbani sangeet and female kirtaniya. Presentation topics and bios can be accessed via the Sikh Studies website at Hofstra.

This year the conference will also host two supplementary film screenings and offer a forum to deepen the discourse around the recent Oak Creek Massacre. The films include Safina Uberoi’s ‘Gurdwara: the Guru’s Portal: a door to document Truth’ and Harjant Gill’s ‘Roots of Love,’ while the pieces related to Oak Creek include Dr. Nikhil Pal Singh’s ‘Remainders of White Supremacy,’ and Dr. Balbinder Singh Bhogal’s ‘Oak Creek Killings: The Denial of a culture of oppression’ (which can be read online).

Guest blog by: Rocco

One of the highlights of fall in NYC is the Sikh Arts and Film Festival which showcases the story of our community via films and is being held November 2-3, 2012. Along with that is a Heritage Gala which is being held November 3, 2012 “to celebrate the rich heritage, culture and traditions of the Sikhs.” In the past dignitaries and business leaders have been selected as Chief Guest and Guest of Honors. Unfortunately, The Chief Guest this year is Nirupama Rao, India’s Ambassador to the United States and the Guest of Honors include Prabhu Dayal, Consul General India, New York and Hardeep Puri, India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

One of the highlights of fall in NYC is the Sikh Arts and Film Festival which showcases the story of our community via films and is being held November 2-3, 2012. Along with that is a Heritage Gala which is being held November 3, 2012 “to celebrate the rich heritage, culture and traditions of the Sikhs.” In the past dignitaries and business leaders have been selected as Chief Guest and Guest of Honors. Unfortunately, The Chief Guest this year is Nirupama Rao, India’s Ambassador to the United States and the Guest of Honors include Prabhu Dayal, Consul General India, New York and Hardeep Puri, India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

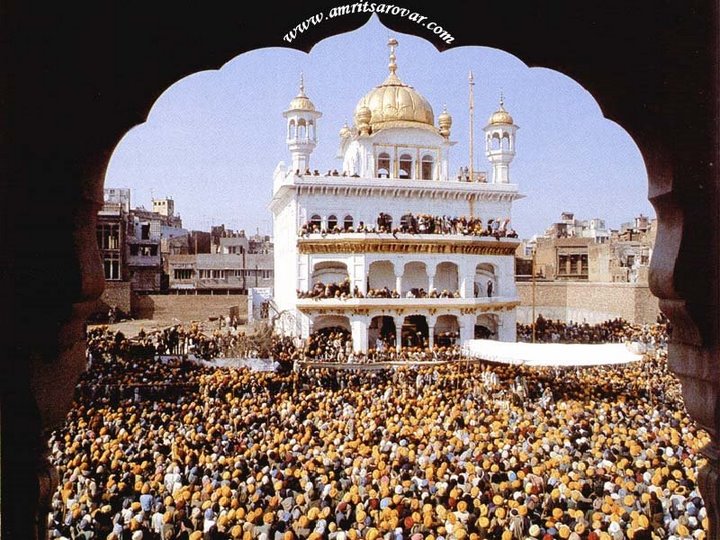

For some, Sikhs having Indian Government representatives as honorees poses no conflict and should be encouraged. One may argue that the attack on Darbar Sahib and Genocide in 1984 are distant events that occurred twenty eight years ago and should be forgotten. One may argue that the civil war which ensued for ten years afterwards in Panjab and led to the death of the tens of thousands of Sikh youth were collateral damage and justifiable in order to preserve the unity of India. One may argue that that struggle for an independent Panjab has reached its nadir and it’s important to “re-Indianize” ourselves and take advantage of the current economic environment.

My last post on the issue of Building Begampura: Confronting Caste raised much concerns and a host of opinions. I am personally committed to raise the voice against apartheid, discrimination, and humiliation that continues to occur in our community due to caste.

Since my last post, jathedar Gurbachan Singh and others have spoken out against the issue of caste-based Gurdwaras. While naming of the Gurdwaras is problematic and may be an important move, much more important is to criticize and shake-up the casteism that led many of these “historically-discriminated” groups to move in this direction after facing abuse at the hands of the “privileged” groups. To deny the context and believe that the root is merely ‘naming’ is on one level merely ‘lip-service’ and on other hand is to take a position against the already-victimized groups. It is not ‘naming’ that is the problem – it’s the casteism, stupid.

Again, while the voice of jathedar Gurbachan Singh and others may be notable, as we have seen with hukamnamas against sex-selective abortion, in and of themselves they will not stop the deeper issues. What is needed are social movements by civic groups. One such initiative is the Pledge Begampura initiative by the Jakara Movement. Read the shabad; learn about the issue; and take the pledge!

Also critical is the growing discussion around the subject in Punjab. Day and Night Television had a recent forum on the subject of caste-based Gurdwaras (pagh salute Pukhraj Singh!). Denial of casteism is not the solution. As the recent issue of the inhumane abuses and attempt to create wage slaves by the landlords of village Mahan Singh Wala, the issue of caste is pertinent and tears at the social fabric of Punjab. Change will come; I hope Sikhs reading this will embrace that change and challenge the inhumanity of casteism.

Aamir Khan’s social sensation “Satyamev Jayate” has highlighted the issue of casteism on a national level. See the episode here.

Below the fold, I have linked a few more recent media discussions on the topic.

Guestblogged by Harinder Singh

Guestblogged by Harinder Singh

Harinder Singh is a co-founder of the Sikh Research Institute and the Panjab Digital Library. He is interested in anything Sikhi, esp. institutional development towards community building. His Twitter handle is @1Force.

I heard as recently as last Sunday at a Baltimore gurduara, that Sikhs don’t know how to make their own decisions. True, and false.

For more than a century (1699-1805), Sikhs made tough, controversial, politically incorrect, yet reached consensus-driven, time-sensitive, and decisive conclusions via the institutions of the Sarbat Khalsa and the Gurmata. And this was accomplished during a century that saw half of Sikh population killed in a single genocidal campaign.

It has taken more than 200 years to dismantle these systems of consensus building; it will take a concerted effort for at least 20 years to revive it. This process will require complete openness and inclusivity. It is a risk worth taking and a solemn opportunity to grasp what others deemed worth dying for!

Sikhs worldwide responded to the recent Rajoana phenomenon with stunning solidarity. Governments, politicians, and spiritualists weren’t sure what was going on. Musicians used the opportunity to wash-off their “sins” of sycophancy from the last Panjab election promos. People-at-large were excited, but they were not prepared. I felt personally that I failed to convince myself of what matters most, and I failed to convince the activists (both the Tweeting and sloganeering kinds) to do something meaningful in any concerted way. I concluded that we self-deluded panthak folks failed everyday-Sikhs at this historical moment with an engagement policy. There was no mechanism to decide what the Panth must do at the crucial tipping point of actionable potential.

The last few weeks, Sikhs around the world have been celebrating the anniversary of the birth of the Khalsa. I intended to do a Vaisakhi post earlier, but travels have kept me from sitting down and writing down some of my reflections until now. I have found myself in small and medium-sized towns throughout the midwestern and southern United States these last two weeks, feeling my outward identity as a Sikh projecting more conspicuously than ever.

NYC's Annual Sikh Day Parade

Consequently, I began thinking a lot about the significance of the Bana that Guru Gobind Singh gave us in 1699. What a fearless, defiant act of revolutionary love it was for Sikhs to wear their identity so visibly in a time when they faced such severe violent repression. A time when it was dangerous to be a Sikh, where being a Sikh meant you were an enemy of the empire, a threat, where there was a price on your head, a target on your back. Yet rather than blending into Indian society and building its movement for sovereignty and justice subversively, the Khalsa wore its identity loudly and proudly so everyone knew very clearly who a Sikh was.

I think about this today as more and more of cut our hair because we can’t take the torment of bullying in schools any more or trim our beards so we look more “professional” at our corporate jobs. Bana seems to have lost its appeal to many, for an ever-expanding list of reasons. Looking back at our history, it never has been easy. And perhaps that is part of the point. I wouldn’t wish the traumatic experience of racist harassment on anyone, but I know very well that I wouldn’t be the person I am today without all the struggles I have dealt with because of my Sikh identity.

Guest blogged by Sharandeep Singh

Sidak, run by Sikh Research Institiute, is a diamond among jewels. It is one program, which after attending, completely changes your outlook on Sikhi, and life – I speak unequivocally when I say there is nothing else like it!

As a graduate of Sidak 2011, I want to share my experience to motivate and inspire whoever reads this to attend, so that you too can join the ranks of people who have enriched and developed their understanding of Sikh culture and history.

The annual retreat, based in Texas may seem daunting, particularly for me—it being my first trip to the US—I arrived with a feeling of trepidation, not fully aware what awaited me in the two weeks ahead. Suffice to say, I was not disappointed.

Within this large South Asian category there co-exist several narrower types of identification that nonetheless cut across the national/religious divide. One of the most powerful ones is Panjabyat. This term of recent coinage, roughly translated as Panjabi identity, refers to the cultural heritage, the social practices, the values shared by all Panjabis, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, Indians, Pakistanis, and increasingly the diaspora. It is heavily loaded with nostalgia for pre-partition undivided Panjab, idealized as a unique space of communal harmony. Its usage tends to be restricted to intellectual, literary, academic or media circles, and although these valorize popular culture in their definition of Panjabyat, the term is not much used by the people. [Emphasis added]

Within this large South Asian category there co-exist several narrower types of identification that nonetheless cut across the national/religious divide. One of the most powerful ones is Panjabyat. This term of recent coinage, roughly translated as Panjabi identity, refers to the cultural heritage, the social practices, the values shared by all Panjabis, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, Indians, Pakistanis, and increasingly the diaspora. It is heavily loaded with nostalgia for pre-partition undivided Panjab, idealized as a unique space of communal harmony. Its usage tends to be restricted to intellectual, literary, academic or media circles, and although these valorize popular culture in their definition of Panjabyat, the term is not much used by the people. [Emphasis added] Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Mill Town Pioneers. Most of Canada’s early Sikh immigrants found work in lumber mills throughout the Pacific Northwest.