The ICC, the Sikhs, and the Indian State

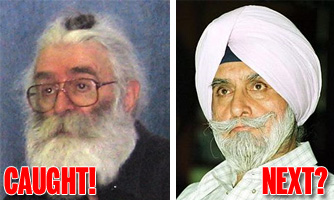

All the headlines are centered on the news of the capture of Bosnian Serb wartime president, Radovan Karadzic. Karadzic has been indicted for genocide in the Bosnia war. Apprehended by government officials, a change in political winds in Serbia now-seeking EU membership has allowed for the present Serbian government to capture the thirteen-year fugitive. The world is now waiting for Karadzic to be transferred to The Hague to  face trial.

face trial.

Karadzic’s soon-expected extradition and last week’s International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor request that genocide charges should be brought against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for state-sponsored pogroms in the Darfur region of Sudan is being watched the world over.

Karadzic’s arrest led to one Munira Subasic, head of a Srebrenica widow’s association (for more information on the Srebrenica Genocide/Massacre, click here), stated

“[Karadzic’s arrest] is confirmation that every criminal will eventually face justice.” [link]

I hope Subasic’s comments ring true. While I celebrate the capture of one tyrant, as a Sikh, my attention wanders (as it tends to) to the situation in Punjab and the Indian State.

Many of us are more informed of the United States’ position with the ICC than that of India. A short recount: then American President, Bill Clinton, signed the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court in 2000, although stating that he would delay sending the treaty to the Senate for ratification until the US government could assess the functioning and jurisdiction of the court. Despite Clinton’s support for the treaty, he was apprehensive of its implementation and the possibility that American war criminals may be brought to justice. Under the administration of George W. Bush, America moved in a very different direction than his predecessor. While Clinton hesitated, Bush Jr. has sought to undermine the ICC completely.

In 2002, the Rome Statute had gained the requisite ratifications of 60 different nations (At present there are over 106 countries that have signed the statute, including Canada, Mexico, most of Europe, Japan, most of South America, and many nations in Africa. A map can be viewed here). However, the Bush administration with its key advocate against the ICC, John Bolton, effectively, “unsigned” its initial intent to join the treaty with the short letter to then UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan:

Dear Mr. Secretary-General:

This is to inform you, in connection with the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court adopted on July 17, 1998, that the United States does not intend to become a party to the treaty. Accordingly, the United States has no legal obligations arising from its signature on December 31, 2000. The United States requests that its intention not to become a party, as expressed in this letter, be reflected in the depositary’s status lists relating to this treaty.

Sincerely,

S/John R. Bolton[link]

Thus while the US position is well-known, as is the ICC positions of its chief UN Security Council opponents: China and Russia, few have ever looked at the reasons India (the second most populous state in the world and the always proud “world’s largest democracy”) refused to sign the Rome Statute and abstained from the final vote. (In fact, India signed a pact with the United States in 2002, seeking to scuttle the ICC, where they agreed not to send each others’ nationals to the ICC.)

A recent article scrutinizing India’s position with the ICC has been published by Thomas Bobinger, a graduate from the Free University of Amsterdam in the Masters in Law and Politics of International Security program. (Thank you Thomas for this correction!) According to his website and blog, he served as a trainee in the trade department of the European Commission Delegation to India, Bhutan, and Nepal.

In the article he cites a number of reasons why India has refused. First looking into the Indian State’s colonial history, he believes that many politicians are weary of neo-colonialism and neo-imperialism from former colonial European powers. Bobinger even goes as far as to say that the fear of neo-colonialism causes

India even today remains suspicious of foreign investment, transnational companies, and a globalised economic order. [link]

However, while such arguments may have carried far more weight during the experiments with Nehruvian authoritarianism, the old days of “suspicion of foreign investment, transnational companies, and a globalised economic order” are long gone and a new Indian middle class has emerged that is completely wedded to such a new economic order. In fact politicians are beginning to bend over backwards to continue to harbor such a new tide and begin comparisons to the rising “business dragon” that is China.

Thus, while this section of the article seemed dated, Bobinger’s insight is keen when he turns to look at the domestic situation within the Indian state. He notes the fears of Indian government authorities with (1) any oversight of the judicial system in India and (2) the inclusion of non-international armed conflict in the jurisdiction of the court.

To the first point, few “Indians” are unaware of the non-functioning of India’s judicial system. Those that have been terrorized by the state know that no justice will be found in the state’s courts. How can the perpetrator also act as the judge?

Bobinger writes of India’s rejection on this point:

Still, India rejected the Rome Statute, calling it a “travesty of law” if it demands of states to constantly prove the viability of its juridical system. Clearly, India had envisaged a role for the ICC in situations where the national juridical system has collapsed completely, as in post-war societies such as Yugoslavia (Lahiri, June 16, 1998). From the wording of the complementarity regime however, India fears that its own system would be judged unable or unwilling to prosecute. [Emphasis added][link]

Ask the people of Kashmir, Gujarat, Punjab, or the Northeastern Territories about their faith in the Indian State’s judicial system to administer justice. Despite its own “citizens” already knowing the answer, the Indian state fears the international community coming to the same conclusion.

Bobinger is aware where the first two salvos may come from:

India feared that the ICC will be used for embarrassing India through attempting to make a case out of the violence in Kashmir an issue seen as of vital importance for national security and thus national sovereignty, stemming from the strategic geographic position and resource richness of Kashmir and Jammu. [link]

However a second one would not be far behind:

However, it is not only the Kashmir conflict that India has to worry about should it accept the jurisdiction of the Court. Without clarity and precision of the crime against humanity (which still lacks a proper definition) (Lahiri, July 17, 1998) India could be subject to trials before the ICC on a range of domestic issues. For instance, the anti-Sikh riots that raged for three days following the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi, on 31 October 1984, by her own Sikh bodyguards, have left a legacy of a targeted community, where many were killed and the perpetrators never properly prosecuted. Even 20 years after that event, the judicial cleaning up process is not finished, despite the knowledge of state policy complicity. There were only few prosecutions and even fewer convictions [Emphasis added] [link]

Impunity continues even today, as documented by groups such as Amnesty International

“In Punjab, the vast majority of police officers responsible for serious human rights violations during the period of civil unrest in the mid-1990s continued to evade justice, despite the recommendations of several judicial inquiries and commissions.” (AI, 2006) [link]

Another reason for India’s fear is the role of the ICC Prosecutor. Bobinger notes:

In addition to State Party and Security Council referrals, the Prosecutor may receive information on crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court provided by other sources, such as individuals or non-governmental organizations. [Emphasis added] [link]

As the Sikhs represent a non-state nation, their only recourse in the existing nation-state framework is the development of non-government organizations that can give them voice in international forums. That such entities may actually be able to influence possible prosecution in a way that India may not be able to flex its military, political, or economic clout produces extreme fear in the perpetrators of pogroms.

So while I do not expect a state such as India that is more than willing to sponsor large-scale murder, pogroms, and even genocide against its own citizenry to become a member of the nations supporting the ICC in the near future, I do believe that Sikhs should continue to place pressure on international organizations to call for an end of impunity by a state that harbors state-terrorists such KP Gill.

Next year, 2009, will mark the 25th year since the storming of Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar and the third Sikh Ghallughara (Holocaust) of 1984. Efforts to mobilize and galvanize world attention to the impunity of Indian state-sponsored terrorism should be placed at the head of worldwide Sikh agenda. Akhand paaths and kirtans are great and serve a purpose, but if we can begin moving the wheels of these international organizations then we may move closer to bringing the victims of this genocide something greater – justice (ensaaf).

I know there are many young Sikh lawyers that have interned/work for various institutions in The Hague, maybe they have some insight. Maybe some of Ensaaf’s volunteers can contribute to this conversation. While I understand the first imperative will be in collecting documentation, how can the Sikh community begin to bring to world attention the crimes against humanity (yes, my claim) perpetrated by people such as KPS Gill (old posts on him can be found here, here, and here), Sumedh Saini, and many others?

Please forward this link or post widely and let the Sikh community begin this conversation.

As an editorial cartoonist and a survivor of the 1984 genocide in Delhi, my response to your thoughts is via the latest Sikhtoon

http://www.sikhtoons.com/GoogleGenPlus.html

As an editorial cartoonist and a survivor of the 1984 genocide in Delhi, my response to your thoughts is via the latest Sikhtoon

http://www.sikhtoons.com/GoogleGenPlus.html

As an alternative to the ICC, I think the most effective platforms for enforcing human rights in the future will be regional courts such as the European Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

The Inter-American court, in the breakthrough case of Velazquez-Rodriguez v. Honduras (1988), established liability for states when they failed to practice "due diligence" to protect human rights, a major milestone in human rights law.

I don't know how much the conversation amongst south asian/asian human rights jurists has developed regarding such an institution, but I think it would be the best forum for future human rights cases stemming from regional conflicts. Civic faith is stronger amongst regional communities than amongst more global communities.

Regional courts may be more culturally sensitive. But the flip side is that they may be more likely to retain local cultural biases.

Enforcing judgments still remains a matter of political will, but regional nations tend to be more intertwined and there already exists political pressure within their relationships.

As an alternative to the ICC, I think the most effective platforms for enforcing human rights in the future will be regional courts such as the European Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

The Inter-American court, in the breakthrough case of Velazquez-Rodriguez v. Honduras (1988), established liability for states when they failed to practice “due diligence” to protect human rights, a major milestone in human rights law.

I don’t know how much the conversation amongst south asian/asian human rights jurists has developed regarding such an institution, but I think it would be the best forum for future human rights cases stemming from regional conflicts. Civic faith is stronger amongst regional communities than amongst more global communities.

Regional courts may be more culturally sensitive. But the flip side is that they may be more likely to retain local cultural biases.

Enforcing judgments still remains a matter of political will, but regional nations tend to be more intertwined and there already exists political pressure within their relationships.

Reema, continuing with your line of argument, does the Indian State belong to any regional court? The only organization I can think of is SAARC, but I am not aware of any court of human rights associated with it? Do you or does anyone else know?

There are no supra-national regional courts in Asia yet. I think this is the direction that should be pushed for though. Garnering political will is difficult, but I think these courts will eventually develop. I think ideally there should be separate courts for central, south, and east asia, but I don't know how resources and politics would play out.

Reema, continuing with your line of argument, does the Indian State belong to any regional court? The only organization I can think of is SAARC, but I am not aware of any court of human rights associated with it? Do you or does anyone else know?

There are no supra-national regional courts in Asia yet. I think this is the direction that should be pushed for though. Garnering political will is difficult, but I think these courts will eventually develop. I think ideally there should be separate courts for central, south, and east asia, but I don’t know how resources and politics would play out.

Ok so assuming this is the case in Asia currently, the push can go in both directions: 1) for establishing such a court system in the future for Asian regional networks and 2) pushing for justice in the current framework.

So as you suggested regional frameworks may be key in the FUTURE, but in the EXISTING framework, is there anything other than the ICC at this moment? If the ICC is the only current outlet then what are the moves the community should begin stirring to bring the matter to international attention?

Ok so assuming this is the case in Asia currently, the push can go in both directions: 1) for establishing such a court system in the future for Asian regional networks and 2) pushing for justice in the current framework.

So as you suggested regional frameworks may be key in the FUTURE, but in the EXISTING framework, is there anything other than the ICC at this moment? If the ICC is the only current outlet then what are the moves the community should begin stirring to bring the matter to international attention?

I'd love to see India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka get together and agree to some sort of regional ICC like court that has jurisdiction over their militaries and politicians. If that ever gets off the ground, there should be textbooks written on the negotiating skills of the active participants and diplomats the world over should bow down to their god-like skills.

I can't help but wonder that as nations develop into the 1st world, that the idea of an overriding judicial body would be less enticing. This is especially relevant to emerging super powers and not necessarily the “weaker” or less significant nations that have strong incentives, whether economic, political, military, etc., to appease trade partners and wealthy nations. There would be nothing better than an external body either independently prosecuting or forcing India to bring to justice the bastards who have perpetrated genocide in Sri Lanka, Gujarat, Kashmir and most of all, Punjab. By any moral or legal standard, justice has not been served, and the Indian legal system is incredibly inefficient, if not corrupt. But the very idea of an ICC or an ICC like organization is paternalistic, almost condescending, to a sovereign nation. You are simultaneously ceding power and acknowledging your inability to manage things yourself, and as all the block quotes above indicate, this is probably India’s motivation to not join. India strives for recognition, equality and respect after being exploited by the western world for decades. I don’t think joining such a paternalistic organization really jives with the pride and mentality that fuels its emergence as a super power. As for a regional court – the mutual hatred aside, why would India cede jurisdiction to an organization that is simultaneously administered by its weaker neighbors? I have very little Indian pride, and almost no Indian nationalistic tendencies, but I’m trying to look at this in an objective manner given the history and emotions that are involved. And I understand why India refuses entry.

Rather than pushing them to join, at this point, I’d stridently call for them to clean up the mess they call a judicial system. I suspect this will inevitably occur as the middle class emerges, businesses develop, and more multi-national corporations enter their markets and all the subsequent conflicts need effecient resolution. As for past crimes, I doubt anything will ever come about. Sikhs have been trying for 25 years, and keep hitting brick walls. Organizations won't help either – the ICC doesn’t seek to retroactively prosecute crimes committed before its July, 2002 inception – this Serb is being prosecuted by a specific war crimes tribunal created after the Yugoslavian conflicts, the ICTY. If anything, perhaps India should create a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, such as what occurred in South Africa after apartheid and elsewhere. But a political party (Congress) and too many people have too much to lose. And if the BJP and their Hindu Nationalists gained power and tried to institute such a commission, it wouldn't be for justice, it'd be to weaken the Congress for political gain on the backs of Sikh genocide.

As for the ICC – some more thoughts. The nations that created the ICC and championed its cause are, 1) extremely and historically stable, 2) not really all that involved with world affairs outside of proxy organizations (UN, NATO), and most of all, 3) poo-poo atrocities committed in less developed and more conflicted nations without doing a god damn thing to actually stop the need for eventual prosecutions. Imagine the ICC acquiring jurisdiction over Omar Al-Bashir, and they somehow were able to prosecute him next year for genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur. They can proclaim justice has been done and sleep at night. Meanwhile, they sat on their hands and permitted hundreds of thousands of innocents to be slaughtered despite presumably possessing the same moral values as they might champion during a prosecution. I’m not even sure of the point beyond political posturing. The ICC is a separate judicial body from nations’ militaries and the UN, but it’s created and administered by the same parties. And it's a joke – it is "justice" after the carnage is over. If they seek justice for such obvious monsters after the conflicts are resolved (and not in the monsters’ favor, thus their ability to apprehend them), either permit a sovereign nation to administer its own justice (Iraq and Saddam) or adopt the tactics of the Mossad and send in a hit squad. Oh wait, then they wouldn't be able to take credit and bask in their moral superiority before the world.

Also, as you’ve raised the subject, it makes perfect sense that the United States refused to ratify it (I’m not sure that Bill Clinton deserves any credit in this regard – his political posturing to ensure his legacy was brilliant. He signed, and then pointed a finger at the Senate knowing that if it ever reached them, it'd be rejected. It's almost as clever as his posturing regarding the Kyoto Protocol . at least he actually expressed uncertainty with the ICC). Even before Iraq/Afghanistan, the US was bearing the vast brunt of policing the world. For example, upwards 90% of the world's waterways are patrolled and policed by the United States, the United States pays for the vast majority of the UN and NATO's budgets, and provides the most troops. The US has bore a military burden, exposed its troops and engaged its military more than any other nation – thanklessly. Then, European nations created some sort of equitable judicial body – one nation, one vote – to exert jurisdiction over not only themselves, but include the United States, its troops, and its politicians…jurisdiction over a nation with one of the most, if not the most, well established, efficient (military and civilian, to a fault – i.e. bad prosecutions), non-political, and active judicial systems in the world. It’s far from perfect, but it’s better than just about any other. Sorry, but given all the inevitable politics that would enter any call for prosecution for the grand crimes over which the ICC presides, any President signing and any Senate ratifying membership is bat-sh*t crazy.

Anyways, I would like nothing more than for justice to be served in India . But, in my opinion, calling for justice and endorsing this particular system to administer justice doesn’t go hand in hand. As for Gill, I’m not one to condone violence, but in his particular case, justice will likely be served when his bodyguards let him down.

I’d love to see India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka get together and agree to some sort of regional ICC like court that has jurisdiction over their militaries and politicians. If that ever gets off the ground, there should be textbooks written on the negotiating skills of the active participants and diplomats the world over should bow down to their god-like skills.

I can’t help but wonder that as nations develop into the 1st world, that the idea of an overriding judicial body would be less enticing. This is especially relevant to emerging super powers and not necessarily the “weaker” or less significant nations that have strong incentives, whether economic, political, military, etc., to appease trade partners and wealthy nations. There would be nothing better than an external body either independently prosecuting or forcing India to bring to justice the bastards who have perpetrated genocide in Sri Lanka, Gujarat, Kashmir and most of all, Punjab. By any moral or legal standard, justice has not been served, and the Indian legal system is incredibly inefficient, if not corrupt. But the very idea of an ICC or an ICC like organization is paternalistic, almost condescending, to a sovereign nation. You are simultaneously ceding power and acknowledging your inability to manage things yourself, and as all the block quotes above indicate, this is probably India’s motivation to not join. India strives for recognition, equality and respect after being exploited by the western world for decades. I don’t think joining such a paternalistic organization really jives with the pride and mentality that fuels its emergence as a super power. As for a regional court – the mutual hatred aside, why would India cede jurisdiction to an organization that is simultaneously administered by its weaker neighbors? I have very little Indian pride, and almost no Indian nationalistic tendencies, but I’m trying to look at this in an objective manner given the history and emotions that are involved. And I understand why India refuses entry.

Rather than pushing them to join, at this point, I’d stridently call for them to clean up the mess they call a judicial system. I suspect this will inevitably occur as the middle class emerges, businesses develop, and more multi-national corporations enter their markets and all the subsequent conflicts need effecient resolution. As for past crimes, I doubt anything will ever come about. Sikhs have been trying for 25 years, and keep hitting brick walls. Organizations won’t help either – the ICC doesn’t seek to retroactively prosecute crimes committed before its July, 2002 inception – this Serb is being prosecuted by a specific war crimes tribunal created after the Yugoslavian conflicts, the ICTY. If anything, perhaps India should create a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, such as what occurred in South Africa after apartheid and elsewhere. But a political party (Congress) and too many people have too much to lose. And if the BJP and their Hindu Nationalists gained power and tried to institute such a commission, it wouldn’t be for justice, it’d be to weaken the Congress for political gain on the backs of Sikh genocide.

As for the ICC – some more thoughts. The nations that created the ICC and championed its cause are, 1) extremely and historically stable, 2) not really all that involved with world affairs outside of proxy organizations (UN, NATO), and most of all, 3) poo-poo atrocities committed in less developed and more conflicted nations without doing a god damn thing to actually stop the need for eventual prosecutions. Imagine the ICC acquiring jurisdiction over Omar Al-Bashir, and they somehow were able to prosecute him next year for genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur. They can proclaim justice has been done and sleep at night. Meanwhile, they sat on their hands and permitted hundreds of thousands of innocents to be slaughtered despite presumably possessing the same moral values as they might champion during a prosecution. I’m not even sure of the point beyond political posturing. The ICC is a separate judicial body from nations’ militaries and the UN, but it’s created and administered by the same parties. And it’s a joke – it is “justice” after the carnage is over. If they seek justice for such obvious monsters after the conflicts are resolved (and not in the monsters’ favor, thus their ability to apprehend them), either permit a sovereign nation to administer its own justice (Iraq and Saddam) or adopt the tactics of the Mossad and send in a hit squad. Oh wait, then they wouldn’t be able to take credit and bask in their moral superiority before the world.

Also, as you’ve raised the subject, it makes perfect sense that the United States refused to ratify it (I’m not sure that Bill Clinton deserves any credit in this regard – his political posturing to ensure his legacy was brilliant. He signed, and then pointed a finger at the Senate knowing that if it ever reached them, it’d be rejected. It’s almost as clever as his posturing regarding the Kyoto Protocol . at least he actually expressed uncertainty with the ICC). Even before Iraq/Afghanistan, the US was bearing the vast brunt of policing the world. For example, upwards 90% of the world’s waterways are patrolled and policed by the United States, the United States pays for the vast majority of the UN and NATO’s budgets, and provides the most troops. The US has bore a military burden, exposed its troops and engaged its military more than any other nation – thanklessly. Then, European nations created some sort of equitable judicial body – one nation, one vote – to exert jurisdiction over not only themselves, but include the United States, its troops, and its politicians…jurisdiction over a nation with one of the most, if not the most, well established, efficient (military and civilian, to a fault – i.e. bad prosecutions), non-political, and active judicial systems in the world. It’s far from perfect, but it’s better than just about any other. Sorry, but given all the inevitable politics that would enter any call for prosecution for the grand crimes over which the ICC presides, any President signing and any Senate ratifying membership is bat-sh*t crazy.

Anyways, I would like nothing more than for justice to be served in India . But, in my opinion, calling for justice and endorsing this particular system to administer justice doesn’t go hand in hand. As for Gill, I’m not one to condone violence, but in his particular case, justice will likely be served when his bodyguards let him down.

Sizzle,

You make a few great points, but there are too many that just defy sound judgement.

Although I only know you from your comments here on this blog, it is obvious that you are a lawyer. It is sort of comic that here you are an advocate of justice, calling for summary execution and believe that sovereignty trumps justice. Too bad Gonzalez isn't hiring for the Justice Department anymore (I keed, I keed!)

Although I don't have time to comb through your response, I just wonder why when you wrote:

Did you not consider that the US unilaterally takes this role. In fact, should any other nation desire to patrol the waterways that America controls they would be punished and America would view it as a challenge to their prominence. Other nations such as India and China will in the upcoming decades begin to assert greater regional control and America will have to acquiesce. In some reasons the speed will be directly tied to the Bush administration's cowboy imperial adventures that upset the balanced-imperial strategy that had been in place for decades.

Well with that aside and all of sizzle's disagreements, I do believe that the ICC provides one avenue for Sikhs to consider. There may be much to the assertion of retroactive prosecutions not being part of its charter, but still the Sikhs may find other courts (in other states) to indict individuals if not the Indian state.

Sizzle,

You make a few great points, but there are too many that just defy sound judgement.

Although I only know you from your comments here on this blog, it is obvious that you are a lawyer. It is sort of comic that here you are an advocate of justice, calling for summary execution and believe that sovereignty trumps justice. Too bad Gonzalez isn’t hiring for the Justice Department anymore (I keed, I keed!)

Although I don’t have time to comb through your response, I just wonder why when you wrote:

Did you not consider that the US unilaterally takes this role. In fact, should any other nation desire to patrol the waterways that America controls they would be punished and America would view it as a challenge to their prominence. Other nations such as India and China will in the upcoming decades begin to assert greater regional control and America will have to acquiesce. In some reasons the speed will be directly tied to the Bush administration’s cowboy imperial adventures that upset the balanced-imperial strategy that had been in place for decades.

Well with that aside and all of sizzle’s disagreements, I do believe that the ICC provides one avenue for Sikhs to consider. There may be much to the assertion of retroactive prosecutions not being part of its charter, but still the Sikhs may find other courts (in other states) to indict individuals if not the Indian state.

Mewa,

Ha. You are correct…I guess it is obvious. But if you knew me outside this blog, you'd know that I'd never work for the government in any capacity, except maybe a public defender to fight back at the system. Though I was delirious from 12 hours of studying when I wrote that post, as I read it again, I think my positions are not only sound, but consistent – far from comic. As I respect your opinions and this is a really interesting discussion, I thought I’d respond and further flesh out my views with a bit more nuance, especially since it contrasts most other commenter’s. Pardon the length – if you want to jump straight into the India and Sikh issues, go for it.

United States and the ICC

As much as Bush's policies might contribute to a shift in priorities, changes in diplomacy, and new international political models, the "balanced-imperial strategy that had been in place for decades" to which you refer hasn't existed since the early 90's, when the Soviets collapsed and before when, the existence of two superpowers maintained relative international stability. Things have been evolving and no consistent model has existed since. The Cold War is, of course, the reason the United States has so much responsibility to this day. It originally had to take the role because no other nation was able or willing. Had it not, the Soviets (the very real threat to the entire western world, including Europe, and whose aggression varied greatly over 50 years) could easily have gained extra footholds. Ever wonder how the Europeans were able to offer their citizenry such great domestic benefits? It's because they expended so little of their budgets on militaries – the United States had them completely covered against the Soviets, the only military threat for decades. Now that it’s gone, the US continues to scale back and redefine its role, the Europeans are forced to readjust budgets in order finance competent militaries (much to the chagrin of citizenry), the European Union arose in part to create an economic competitor to the United States and protect European interests, and international affairs are in constant flux without the anchor that two competing superpowers formerly provided. Europeans are free to posture and judge all they want because they are still not bound with any real expectations, responsibility, or commitments (except to themselves) and can, for the most part, rely on the United States to commit resources and take action when they fail to do so. As this paradigm evolves and new conflicts arise, I don't agree that the US would automatically reject others’ willingness to assist as a challenge to its prominence – I think it would all depend on who is volunteering, specifically, whether they are a strategic ally. That’s not arrogance, that’s politics and long term strategy. If it helps, imagine all this with a competent president, a skilled diplomat who still has America’s best interests as the top priority.

Tying back to the subject of this thread, the US is still the nation that would be most exposed to the jurisdiction of the ICC (acts almost always perpetrated by military force) as a result of its prominent role in international affairs and frequent military use, and thus has the most to lose with almost zero gain. Given the current international political climate and how the US is affected (irrespective of recent policies, the current demonstrates the possible, where the US, the big man on the mountain, is under constant and heavy scrutiny as other nations posture to their own political advantage), given the "one nation-one vote" model despite the massive disparities in responsibilities, roles and understanding of individual nations, and given that the potential of the ICC as a political instrument to be wielded with the benefit of hindsight, I still maintain that the United States would be daft to join. I can also understand why India (and China and Russia) refuses to join – for the different purposes I articulated in my prior post, and perhaps for similar reasons as the United States – fear of shaming. If nations wish to join as recognition of their moral values, commitment to their sense of justice, as a safety net against future tyrants, assurance to its own citizenry, for purely symbolic purposes, and as an actual method by which to prosecute war criminals, it is each nation’s prerogative and I have no qualms with the ICC’s existence or nations’ involvement.

INDIA, SOVREIGNTY and the ICC

All the above said, as I mentioned in my prior post, there is nothing I desire more than for outside body, such as an ICC, to pass judgment and enforce punishment on those who perpetrated war crimes where India has repeatedly failed to do so. I may have made a misstatement by writing that justice and the ICC don’t go hand in hand. I meant to say that justice and the ICC don’t necessarily have to go hand in hand, or to be even clearer, the ICC doesn’t necessarily bring about justice. I then close with a certain sentiment towards KPS Gill, the interjection of which, you seem to have found comical. Given my objective reasons for understanding why India refuses to join the ICC, I thus have to weigh my desire for justice with consistently applied principles of sovereignty. Consistency and precedent are not comical, I assure you.

So first, to the issue of sovereignty. The basics: I believe in democracy. I believe in autonomous self-rule. I believe in certain unalienable rights, and so I believe in a democratic republic, an organized governmental system that represents the will of its people but is kept in check by each individual citizen’s unalienable rights. Such a system will vary from place to place, as will the definition of unalienable rights to a slight degree (universal health care or not?) to reflect the preference of each nation’s citizens. Such governments account for the West, almost the entire 1st world, and much of the second world. This “self-rule” is touted, respected and is the “preferred” system – it is the epitome of sovereignty, the very concept of which is rooted in individual rights to be determined collectively by individual citizens. A judicial or justice system operates within this system. Without the existence of a sovereign nation and the democratic methods by which to determine the laws that underlie justice, a justice system would not even exist. Thus, sovereignty and justice go hand in hand to serve each individual citizens.

India is a sovereign nation with a constitution, elected representatives who pass its laws, individual rights, and a judicial system to interpret it all. Indian laws prohibit murder, battery, rape, etc.. Indian laws prohibit accomplice to any of those crimes. Indian laws likely prohibit the solicitation or order of those crimes. Violations of those crimes are prosecuted through the judicial system. While India’s judicial system is woefully inefficient and lacking in many regards, it is the system that has been instituted and administered by elected (or appointed by those who are elected) individuals. It is the system of sovereign nation to serve its citizens.

So how did the blatant violation of laws and the most basic unalienable rights go unprosecuted? What of the right to not be killed by your own nation’s military? What of the right to not be beaten or killed by murderous mobs of citizens? What of the right to not be arbitrarily detained by police and subjected to brutal torture? Laws prohibiting such action existed, those laws were obviously violated, but no one was prosecuted. How? Why? Where does the blame lie? Should an outside force have intervened to enforce India’s own laws or an outside set of laws?

First, respected (in many quarters) and elected figures disagree as to the tactics adopted by the military. On one side, some argue that the military was acting to put down a terroristic, separatist uprising, and there was no other available course of action. On the other side (which 99.9% of us are on), some argue that the military was used and exploited by opportunistic politicians to take murderous action against representatives of an increasingly and highly disproportionately powerful minority in order to crush their spirit and bolster political support among easily manipulated majority factions who were completely unaware of the back-room deals, political scheming, and miscalculations that ended in the climactic military action. As for the post-assassination riots and murders, two sides also exist. On one side, some might say, “F**k ‘em, they asked for it,” or, that individual citizens were carried away with their emotions and love for Hindustan, that they may have committed crimes, but that it was a crazy time, it wasn’t too bad, and only a few people died; that all should just move on and not rehash the past. On the other side (which 100% of us are on), some argue that the riots were orchestrated by shrewd politicians who sought, in the face of a disruptive “national tragedy” to act on their own biases and hatred and simultaneously solidify their reputation and support among factions who were decidedly anti-Sikh and strongly nationalistic. As for the tactics of the Punjab police, again, two sides. First, some argue that the police needed to ensure that the separatist movement was fully quelled, and that given the history and potential consequences of failure, just about all tactics were permissible. People who were subjected to their methods were probably terrorists or assisting the terrorists. “Plus, weren’t most of the Punjabi police Sikhs? Led by that sharp looking fellow, KPS Gill? I like him – he’s a proud Indian. He had his priorities straight – India first. I hope they promote him.” Meanwhile, we will argue that arrests, “disappearings” and general tactics were a highly organized, illegal and unconstitutional politically motivated military campaign, that the police were the terrorists, indiscriminately using violence against innocents to punish by proxy, developing an environment of fear, and summarily torturing and executing anyone suspected of wrongdoing – all in violation of Indian laws and any notion of unalienable rights.

I wrote out the preceding to illustrate that there are two sides to the history, both of which garner a wide level of support. Thus, as hard as it is to admit, neither is automatically objectively correct in the eyes of others. While we believe it is objectively correct, it isn’t obvious that war criminals were purposely committing genocide, ethnic cleansing and other crimes against humanity for their own political purposes. This isn’t as clear cut as a Saddam Hussien, Slobodon Milosevic, or Omar al-Bashir – all of this occurred in a developed nation recognized as the “world’s largest democracy,” which is partly why it was unprecedented in the modern era and particularly stunning. The underlying politics, the crimes of Khalistanis, and the meetings and maneuvering in the six years preceding 1984 muddle the issue tremendously. This is exactly where a trial would be useful – where evidence can be presented, where a trial can parse through the stories, the witness accounts, where victims and suspects can present their sides, and suspects and their actions may be judged. But for all of the obvious illegalities that took place, not a single person has been prosecuted by Indian authorities. How and why? Because it was nearly impossible to separate the politics from the crimes, and as I mentioned above, too many people had too much to lose. The most powerful and interested parties took the position of the first “voice” in each of the three sets of incidents, and thus didn’t initiate any action in the judicial system. It would have proven too embarassing. It’s not that the alleged crimes weren’t already illegal under Indian law – it’s that India’s elected officials chose to not enforce laws that it otherwise enforced, or merely excused them as emergency military actions (as our own constitution may permit martial law).

Obviously, this is complete bullsh*t and a disgusting failure. But, should these failures force the Indian government to cede jurisdiction and investigatory powers over those crimes? Should it force the Indian government to turn over custody of all independently determined suspects to an outside, international court comprised of the citizens of other nations, a court that operates by its own rules, own laws, and own procedures? While my desire for justice wishes that it would, I also recognize that forcing such action would violate every underlying principle of individual and national sovereignty – a concept I hold in pretty high regard, and a concept that must be addressed with caution. While the rights of victims were violated and justice is sought, it is at this point when we must also concern ourselves with the rights of the accused, also members and individual citizens of a sovereign nation. The only way such transfer of jurisdiction is permissible is if the Indian government, through its elected representatives and thus through individual citizens, were to voluntarily enter into the ICC or a similar body and recognize their right to investigate and prosecute. Until India does so, I can’t condone taking actual legal action that results in any legal sanction against the accused. It truly is a matter of principle and a matter of precedent.

Again – this is an objective analysis that seeks to explain to you how I could possibly simultaneously desire justice but also reject the ICC as an avenue for justice given India’s stance. I'm not really laughing.

Finally, you mention that I’m a proponent of summary executions and that this somehow contradicts my advocacy for justice, comically so. I’ll disregard the “summary” part and ask – who’s to say an execution is not justice? I’m opposed to the death penalty as punishment to be administered by any general court system. My own involvement with the courts, personally and professionally, has highlighted its fallibility and profound weaknesses. Ordering the taking of a life through general legal systems with little oversight is far from appropriate. That’s not to say, however, that I think that an execution is not justice. If I were to wake up in the middle of the night to find my family being harmed by an intruder, I am pretty sure that I’d simultaneously remove my family from harm and administer some justice with my shotgun. Similarly, in the context of war crimes, if a nation can bring about an end to mass murder militarily by eliminating the leading figures in genocide, I am not morally opposed, though I recognize the slippery slope arguments and issues of sovereignty. If the unique situation arose where a war criminal who openly and unabashedly proclaimed his involvement with genocide and mass murder or if his involvement and oversight was guaranteed, and who defended his actions or tried to justify them, were captured alive – well then, prosecute, convict and throw them in a dark hole for life if you’re a peoples or nation opposed to the death penalty out of reverence for all human life as did the UN with Slobo Milocevic. If you’re a people who are a-ok with the death penalty, administer your justice and execute them, as was done with leading Nazi’s and Saddam. I’m fine with the administration of the death penalty in such instances because the chance of fallibility is nonexistent.

It is more complex when the crimes are past and the perpetrators still walk free, their involvement and actions undeniable, guaranteed. Such is the case with KPS Gill and certain members of the Congress party. Legally, the options seem to be closed. As I said at the end of my last post, there is a distinct possibility of comeuppance is yet to be realized, something I wouldn’t particularly mind, but can’t really endorse or support.

But, I do think that Jodha probably had it best at the conclusion of his post. At this point, it is incumbent upon Sikhs to ensure that the deaths and sacrifices were not in vain even if justice will never be served. Too many of our own people have no idea what occurred. Too many historians are unaware of the complexities and politics behind the conflict or were susceptible to the misniformation. As do the Jews in remembering the Holocaust, Sikhs must ensure that the past is not forgotten or dismissed and must continue to propagate the truth harder than Indian propagates its campaign of misinformation. I don’t think that will be much of a problem since many Sikhs, especially western Sikhs, will never forget.

That said, at this point, 25 years later, it may be worth considering a new approach. I mentioned the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in my above post. I misstated that something similar may work to achieve justice. Actually, the TRC was not concerned with justice per se, but was concerned with closure to facilitate future relations; recognition of the wrongs and the confessions to crimes without legal consequence in order to provide closure and begin the healing process. I know we are a feisty people and we may never stop our pursuit for justice until every last perpetrator is dead or gone. But, I can’t help but wonder if the admission and reconciliation route may prove more beneficial and constructive at this stage in history.

Mewa,

Ha. You are correct…I guess it is obvious. But if you knew me outside this blog, you’d know that I’d never work for the government in any capacity, except maybe a public defender to fight back at the system. Though I was delirious from 12 hours of studying when I wrote that post, as I read it again, I think my positions are not only sound, but consistent – far from comic. As I respect your opinions and this is a really interesting discussion, I thought I’d respond and further flesh out my views with a bit more nuance, especially since it contrasts most other commenter’s. Pardon the length – if you want to jump straight into the India and Sikh issues, go for it.

United States and the ICC

As much as Bush’s policies might contribute to a shift in priorities, changes in diplomacy, and new international political models, the “balanced-imperial strategy that had been in place for decades” to which you refer hasn’t existed since the early 90’s, when the Soviets collapsed and before when, the existence of two superpowers maintained relative international stability. Things have been evolving and no consistent model has existed since. The Cold War is, of course, the reason the United States has so much responsibility to this day. It originally had to take the role because no other nation was able or willing. Had it not, the Soviets (the very real threat to the entire western world, including Europe, and whose aggression varied greatly over 50 years) could easily have gained extra footholds. Ever wonder how the Europeans were able to offer their citizenry such great domestic benefits? It’s because they expended so little of their budgets on militaries – the United States had them completely covered against the Soviets, the only military threat for decades. Now that it’s gone, the US continues to scale back and redefine its role, the Europeans are forced to readjust budgets in order finance competent militaries (much to the chagrin of citizenry), the European Union arose in part to create an economic competitor to the United States and protect European interests, and international affairs are in constant flux without the anchor that two competing superpowers formerly provided. Europeans are free to posture and judge all they want because they are still not bound with any real expectations, responsibility, or commitments (except to themselves) and can, for the most part, rely on the United States to commit resources and take action when they fail to do so. As this paradigm evolves and new conflicts arise, I don’t agree that the US would automatically reject others’ willingness to assist as a challenge to its prominence – I think it would all depend on who is volunteering, specifically, whether they are a strategic ally. That’s not arrogance, that’s politics and long term strategy. If it helps, imagine all this with a competent president, a skilled diplomat who still has America’s best interests as the top priority.

Tying back to the subject of this thread, the US is still the nation that would be most exposed to the jurisdiction of the ICC (acts almost always perpetrated by military force) as a result of its prominent role in international affairs and frequent military use, and thus has the most to lose with almost zero gain. Given the current international political climate and how the US is affected (irrespective of recent policies, the current demonstrates the possible, where the US, the big man on the mountain, is under constant and heavy scrutiny as other nations posture to their own political advantage), given the “one nation-one vote” model despite the massive disparities in responsibilities, roles and understanding of individual nations, and given that the potential of the ICC as a political instrument to be wielded with the benefit of hindsight, I still maintain that the United States would be daft to join. I can also understand why India (and China and Russia) refuses to join – for the different purposes I articulated in my prior post, and perhaps for similar reasons as the United States – fear of shaming. If nations wish to join as recognition of their moral values, commitment to their sense of justice, as a safety net against future tyrants, assurance to its own citizenry, for purely symbolic purposes, and as an actual method by which to prosecute war criminals, it is each nation’s prerogative and I have no qualms with the ICC’s existence or nations’ involvement.

INDIA, SOVREIGNTY and the ICC

All the above said, as I mentioned in my prior post, there is nothing I desire more than for outside body, such as an ICC, to pass judgment and enforce punishment on those who perpetrated war crimes where India has repeatedly failed to do so. I may have made a misstatement by writing that justice and the ICC don’t go hand in hand. I meant to say that justice and the ICC don’t necessarily have to go hand in hand, or to be even clearer, the ICC doesn’t necessarily bring about justice. I then close with a certain sentiment towards KPS Gill, the interjection of which, you seem to have found comical. Given my objective reasons for understanding why India refuses to join the ICC, I thus have to weigh my desire for justice with consistently applied principles of sovereignty. Consistency and precedent are not comical, I assure you.

So first, to the issue of sovereignty. The basics: I believe in democracy. I believe in autonomous self-rule. I believe in certain unalienable rights, and so I believe in a democratic republic, an organized governmental system that represents the will of its people but is kept in check by each individual citizen’s unalienable rights. Such a system will vary from place to place, as will the definition of unalienable rights to a slight degree (universal health care or not?) to reflect the preference of each nation’s citizens. Such governments account for the West, almost the entire 1st world, and much of the second world. This “self-rule” is touted, respected and is the “preferred” system – it is the epitome of sovereignty, the very concept of which is rooted in individual rights to be determined collectively by individual citizens. A judicial or justice system operates within this system. Without the existence of a sovereign nation and the democratic methods by which to determine the laws that underlie justice, a justice system would not even exist. Thus, sovereignty and justice go hand in hand to serve each individual citizens.

India is a sovereign nation with a constitution, elected representatives who pass its laws, individual rights, and a judicial system to interpret it all. Indian laws prohibit murder, battery, rape, etc.. Indian laws prohibit accomplice to any of those crimes. Indian laws likely prohibit the solicitation or order of those crimes. Violations of those crimes are prosecuted through the judicial system. While India’s judicial system is woefully inefficient and lacking in many regards, it is the system that has been instituted and administered by elected (or appointed by those who are elected) individuals. It is the system of sovereign nation to serve its citizens.

So how did the blatant violation of laws and the most basic unalienable rights go unprosecuted? What of the right to not be killed by your own nation’s military? What of the right to not be beaten or killed by murderous mobs of citizens? What of the right to not be arbitrarily detained by police and subjected to brutal torture? Laws prohibiting such action existed, those laws were obviously violated, but no one was prosecuted. How? Why? Where does the blame lie? Should an outside force have intervened to enforce India’s own laws or an outside set of laws?

First, respected (in many quarters) and elected figures disagree as to the tactics adopted by the military. On one side, some argue that the military was acting to put down a terroristic, separatist uprising, and there was no other available course of action. On the other side (which 99.9% of us are on), some argue that the military was used and exploited by opportunistic politicians to take murderous action against representatives of an increasingly and highly disproportionately powerful minority in order to crush their spirit and bolster political support among easily manipulated majority factions who were completely unaware of the back-room deals, political scheming, and miscalculations that ended in the climactic military action. As for the post-assassination riots and murders, two sides also exist. On one side, some might say, “F**k ‘em, they asked for it,” or, that individual citizens were carried away with their emotions and love for Hindustan, that they may have committed crimes, but that it was a crazy time, it wasn’t too bad, and only a few people died; that all should just move on and not rehash the past. On the other side (which 100% of us are on), some argue that the riots were orchestrated by shrewd politicians who sought, in the face of a disruptive “national tragedy” to act on their own biases and hatred and simultaneously solidify their reputation and support among factions who were decidedly anti-Sikh and strongly nationalistic. As for the tactics of the Punjab police, again, two sides. First, some argue that the police needed to ensure that the separatist movement was fully quelled, and that given the history and potential consequences of failure, just about all tactics were permissible. People who were subjected to their methods were probably terrorists or assisting the terrorists. “Plus, weren’t most of the Punjabi police Sikhs? Led by that sharp looking fellow, KPS Gill? I like him – he’s a proud Indian. He had his priorities straight – India first. I hope they promote him.” Meanwhile, we will argue that arrests, “disappearings” and general tactics were a highly organized, illegal and unconstitutional politically motivated military campaign, that the police were the terrorists, indiscriminately using violence against innocents to punish by proxy, developing an environment of fear, and summarily torturing and executing anyone suspected of wrongdoing – all in violation of Indian laws and any notion of unalienable rights.

I wrote out the preceding to illustrate that there are two sides to the history, both of which garner a wide level of support. Thus, as hard as it is to admit, neither is automatically objectively correct in the eyes of others. While we believe it is objectively correct, it isn’t obvious that war criminals were purposely committing genocide, ethnic cleansing and other crimes against humanity for their own political purposes. This isn’t as clear cut as a Saddam Hussien, Slobodon Milosevic, or Omar al-Bashir – all of this occurred in a developed nation recognized as the “world’s largest democracy,” which is partly why it was unprecedented in the modern era and particularly stunning. The underlying politics, the crimes of Khalistanis, and the meetings and maneuvering in the six years preceding 1984 muddle the issue tremendously. This is exactly where a trial would be useful – where evidence can be presented, where a trial can parse through the stories, the witness accounts, where victims and suspects can present their sides, and suspects and their actions may be judged. But for all of the obvious illegalities that took place, not a single person has been prosecuted by Indian authorities. How and why? Because it was nearly impossible to separate the politics from the crimes, and as I mentioned above, too many people had too much to lose. The most powerful and interested parties took the position of the first “voice” in each of the three sets of incidents, and thus didn’t initiate any action in the judicial system. It would have proven too embarassing. It’s not that the alleged crimes weren’t already illegal under Indian law – it’s that India’s elected officials chose to not enforce laws that it otherwise enforced, or merely excused them as emergency military actions (as our own constitution may permit martial law).

Obviously, this is complete bullsh*t and a disgusting failure. But, should these failures force the Indian government to cede jurisdiction and investigatory powers over those crimes? Should it force the Indian government to turn over custody of all independently determined suspects to an outside, international court comprised of the citizens of other nations, a court that operates by its own rules, own laws, and own procedures? While my desire for justice wishes that it would, I also recognize that forcing such action would violate every underlying principle of individual and national sovereignty – a concept I hold in pretty high regard, and a concept that must be addressed with caution. While the rights of victims were violated and justice is sought, it is at this point when we must also concern ourselves with the rights of the accused, also members and individual citizens of a sovereign nation. The only way such transfer of jurisdiction is permissible is if the Indian government, through its elected representatives and thus through individual citizens, were to voluntarily enter into the ICC or a similar body and recognize their right to investigate and prosecute. Until India does so, I can’t condone taking actual legal action that results in any legal sanction against the accused. It truly is a matter of principle and a matter of precedent.

Again – this is an objective analysis that seeks to explain to you how I could possibly simultaneously desire justice but also reject the ICC as an avenue for justice given India’s stance. I’m not really laughing.

Finally, you mention that I’m a proponent of summary executions and that this somehow contradicts my advocacy for justice, comically so. I’ll disregard the “summary” part and ask – who’s to say an execution is not justice? I’m opposed to the death penalty as punishment to be administered by any general court system. My own involvement with the courts, personally and professionally, has highlighted its fallibility and profound weaknesses. Ordering the taking of a life through general legal systems with little oversight is far from appropriate. That’s not to say, however, that I think that an execution is not justice. If I were to wake up in the middle of the night to find my family being harmed by an intruder, I am pretty sure that I’d simultaneously remove my family from harm and administer some justice with my shotgun. Similarly, in the context of war crimes, if a nation can bring about an end to mass murder militarily by eliminating the leading figures in genocide, I am not morally opposed, though I recognize the slippery slope arguments and issues of sovereignty. If the unique situation arose where a war criminal who openly and unabashedly proclaimed his involvement with genocide and mass murder or if his involvement and oversight was guaranteed, and who defended his actions or tried to justify them, were captured alive – well then, prosecute, convict and throw them in a dark hole for life if you’re a peoples or nation opposed to the death penalty out of reverence for all human life as did the UN with Slobo Milocevic. If you’re a people who are a-ok with the death penalty, administer your justice and execute them, as was done with leading Nazi’s and Saddam. I’m fine with the administration of the death penalty in such instances because the chance of fallibility is nonexistent.

It is more complex when the crimes are past and the perpetrators still walk free, their involvement and actions undeniable, guaranteed. Such is the case with KPS Gill and certain members of the Congress party. Legally, the options seem to be closed. As I said at the end of my last post, there is a distinct possibility of comeuppance is yet to be realized, something I wouldn’t particularly mind, but can’t really endorse or support.

But, I do think that Jodha probably had it best at the conclusion of his post. At this point, it is incumbent upon Sikhs to ensure that the deaths and sacrifices were not in vain even if justice will never be served. Too many of our own people have no idea what occurred. Too many historians are unaware of the complexities and politics behind the conflict or were susceptible to the misniformation. As do the Jews in remembering the Holocaust, Sikhs must ensure that the past is not forgotten or dismissed and must continue to propagate the truth harder than Indian propagates its campaign of misinformation. I don’t think that will be much of a problem since many Sikhs, especially western Sikhs, will never forget.

That said, at this point, 25 years later, it may be worth considering a new approach. I mentioned the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in my above post. I misstated that something similar may work to achieve justice. Actually, the TRC was not concerned with justice per se, but was concerned with closure to facilitate future relations; recognition of the wrongs and the confessions to crimes without legal consequence in order to provide closure and begin the healing process. I know we are a feisty people and we may never stop our pursuit for justice until every last perpetrator is dead or gone. But, I can’t help but wonder if the admission and reconciliation route may prove more beneficial and constructive at this stage in history.

Sizzle,

Ok I don't want to hijack this post, so I am going to confine myself to the topic of the ICC rather than move towards imperial strategy. However, I do want to comment that a "model" is already appearing. For the time being the US will maintain its status as the global power, but will be challenged regionally by a number of different groups that will become regional hegemons: China increasingly in East Asia, India in South Asia, the EU's power will increase, possibly Iran in non-Arab West Asia, Russia, Brazil, etc. America will be less able to get away with pushing its agenda upon these nations or nations that are their satellites. The "wiggle room" is about to be severely curtailed.

Your right the US and others will continue to refuse to join. Why would one want to subject themselves to the rule-of-law, when they are in the position of "might makes right"?

However, as you said:

I hope the highlighted ones are important to the American citizenry and they push their representatives to have the US join the ICC as well.

You state almost as an article of faith that you believe in "inalienable" rights, thus there has to be a move to create an institution that can enforce those rights. Otherwise at the discretion of power, things can go awry.

Here is where your understanding possibly of Punjab's particular situation limits the discussion. I am not discussing Operation Bluestar or the period prior. I AM talking about the period from 1986-1995 where Punjab was a police state. KPS Gill's crimes were during this period. Contrary to your comments, Indian laws WERE NOT violated in Punjab. In fact the Indian State passed an amendment in 1987 that was in effect until 1993 (which was the bulk of the violent period) that abrogated the constition. Emergency Powers were given to state authorities – in essence martial law was declared.

The situation in India is not very stunning if you read the politics of Asia and other decolonized states. In fact, India's situation has been predicted since 1947. It is not so much that you are opening my eyes to "two sides of history," all I am saying is that Sikhs that committed crime should be punished and the Indian State officials that committed crimes should be punished. Since the Indian State is unable to prosecute itself and shows complacency, then Sikhs will have to look to other bodies for justice.

While you may disagree on principle, I do hope that Sikhs find a way to bring people like KPS Gill to justice through a route such as Spain and Pinochet and universal jurisdiction.

However, as you said in your conclusion, I agree with you there. Well said!

Sizzle,

Ok I don’t want to hijack this post, so I am going to confine myself to the topic of the ICC rather than move towards imperial strategy. However, I do want to comment that a “model” is already appearing. For the time being the US will maintain its status as the global power, but will be challenged regionally by a number of different groups that will become regional hegemons: China increasingly in East Asia, India in South Asia, the EU’s power will increase, possibly Iran in non-Arab West Asia, Russia, Brazil, etc. America will be less able to get away with pushing its agenda upon these nations or nations that are their satellites. The “wiggle room” is about to be severely curtailed.

Your right the US and others will continue to refuse to join. Why would one want to subject themselves to the rule-of-law, when they are in the position of “might makes right”?

However, as you said:

I hope the highlighted ones are important to the American citizenry and they push their representatives to have the US join the ICC as well.

You state almost as an article of faith that you believe in “inalienable” rights, thus there has to be a move to create an institution that can enforce those rights. Otherwise at the discretion of power, things can go awry.

Here is where your understanding possibly of Punjab’s particular situation limits the discussion. I am not discussing Operation Bluestar or the period prior. I AM talking about the period from 1986-1995 where Punjab was a police state. KPS Gill’s crimes were during this period. Contrary to your comments, Indian laws WERE NOT violated in Punjab. In fact the Indian State passed an amendment in 1987 that was in effect until 1993 (which was the bulk of the violent period) that abrogated the constition. Emergency Powers were given to state authorities – in essence martial law was declared.

The situation in India is not very stunning if you read the politics of Asia and other decolonized states. In fact, India’s situation has been predicted since 1947. It is not so much that you are opening my eyes to “two sides of history,” all I am saying is that Sikhs that committed crime should be punished and the Indian State officials that committed crimes should be punished. Since the Indian State is unable to prosecute itself and shows complacency, then Sikhs will have to look to other bodies for justice.

While you may disagree on principle, I do hope that Sikhs find a way to bring people like KPS Gill to justice through a route such as Spain and Pinochet and universal jurisdiction.

However, as you said in your conclusion, I agree with you there. Well said!

ah, my mistake. didn't look up, but i suspected that some sort of martial law may have been in play given the complacensy. not all that surprising, either, considering indira gandhi was able to suspend the constitution in the 1970's when she was about to lose a vote of confidence.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_jurisdicti…

the idea of universal jurisdiction hadn't even occurred to be during this discussion, but is, obviously, very applicable. and reading the wiki article above, i am obviously sympathetic to Kissinger's criticisms towards it in regards to sovreign rights. that wiki article says in one para what took me about 13 pages. anyways, i've always been wary of the concept of "international law" – it is impossible to determine from where, exactly, it derives its jurisdiction. the only logical conclusion as a source, as you astutely pointed out, are "inalienable rights." or more precisely and strongly, "natural rights" a la John Locke. i believe in natural rights. and as i think of this – how strange it is to cite a reliance on inalienable or natural rights to justify and support an intrusion on existing social contracts and the concept of sovreignty. i wish we had this convo when i was in undergrad – could have made for a good poli sci or philosophy senior thesis.

anyways, this could go on forever. but, having the topic raised, thinking about it pretty hard, writing, responding, etc….learned a lot of good stuff. good thread. thanks. i'm done.

ah, my mistake. didn’t look up, but i suspected that some sort of martial law may have been in play given the complacensy. not all that surprising, either, considering indira gandhi was able to suspend the constitution in the 1970’s when she was about to lose a vote of confidence.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_jurisdiction

the idea of universal jurisdiction hadn’t even occurred to be during this discussion, but is, obviously, very applicable. and reading the wiki article above, i am obviously sympathetic to Kissinger’s criticisms towards it in regards to sovreign rights. that wiki article says in one para what took me about 13 pages. anyways, i’ve always been wary of the concept of “international law” – it is impossible to determine from where, exactly, it derives its jurisdiction. the only logical conclusion as a source, as you astutely pointed out, are “inalienable rights.” or more precisely and strongly, “natural rights” a la John Locke. i believe in natural rights. and as i think of this – how strange it is to cite a reliance on inalienable or natural rights to justify and support an intrusion on existing social contracts and the concept of sovreignty. i wish we had this convo when i was in undergrad – could have made for a good poli sci or philosophy senior thesis.

anyways, this could go on forever. but, having the topic raised, thinking about it pretty hard, writing, responding, etc….learned a lot of good stuff. good thread. thanks. i’m done.

Was just skimming this old topic, but had to add that yes I do believe that "natural rights" trumps all else. Once "natural rights" or "inalienable rights" have been abrogated, then old existing social contracts and sovereignty is useless.

Was just skimming this old topic, but had to add that yes I do believe that “natural rights” trumps all else. Once “natural rights” or “inalienable rights” have been abrogated, then old existing social contracts and sovereignty is useless.

There are international treaties like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and there is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the General Assembly of the UN, confirmed to be jus cogens, thus applicable to all states.

Yes I would like to read that textbook about negotiation, too, if there ever is a regional court of human rights, especially including India and Pakistan:)

It is delightful to see that some of the Articles I write are actually read and discussed. Thank you for that.

And on two last notes: I actually wrote this article as a student of the Free University of Amsterdam, Netherlands, during my Master in Law and Politics of International Security. In Maastricht I was during my Bachelor, so maybe knowing that it comes from a Master student, gives it more weight, I don't know:).

And secondly, during my time in India, I made contact with a former Chief Judge of India, and he advocated research in the area of e-peace, alongside research into e-commerce, e-networking and cyber war defensive capabilities. So there is hope for India.:)

There are international treaties like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and there is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the General Assembly of the UN, confirmed to be jus cogens, thus applicable to all states.

Yes I would like to read that textbook about negotiation, too, if there ever is a regional court of human rights, especially including India and Pakistan:)

It is delightful to see that some of the Articles I write are actually read and discussed. Thank you for that.

And on two last notes: I actually wrote this article as a student of the Free University of Amsterdam, Netherlands, during my Master in Law and Politics of International Security. In Maastricht I was during my Bachelor, so maybe knowing that it comes from a Master student, gives it more weight, I don’t know:).

And secondly, during my time in India, I made contact with a former Chief Judge of India, and he advocated research in the area of e-peace, alongside research into e-commerce, e-networking and cyber war defensive capabilities. So there is hope for India.:)

Correction appreciated and noted Thomas!

Thanks for visiting our blog. Could you maybe give more information about the treaties you mentioned. Also what is e-peace?

Correction appreciated and noted Thomas!

Thanks for visiting our blog. Could you maybe give more information about the treaties you mentioned. Also what is e-peace?

uff… more infos on the treaties, you would get by looking them up:

http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b3ccpr.htm

There are also a lot of cases by the European Court of Human Rights, though of course not applicable to India, but if you are interested in the legal reasoning, just search for ECHR and go on their website.

@ e-peace: well that is the problem, everybody talks about e-war, e-commerce, but nobody talks about e-peace. That is why this speaker asked for more research into it. I guess it is not actually a term, yet, but the fact alone that he thinks about things like that shows that some people think about how to put neutral objects to a positive advantage. When I think about e-peace, I think of the web-communities like Facebook, Orkut etc, and what they do for mutual understanding and dialogue, cultural exchange and against stereotypes, I also think of e-peace as the negative of cyber war, so it would mean technological developments against electronic warfare, date and privacy protection, peace on the internet, and the fight against virus, spam, cyber attacks, data smuggling and theft, child pornography, good governance of the internet, neutrality of the internet, accessability and provision of internet, the prohibition of a two-class internet, where rich persons would have access to more information than poor persons, intellectual property rights and copyrights and the fight against their infringement. And lastly, thinking of e-peace the communicational aspect, the trust and confidance building, the sharing of information and news, and community building in general.

I know all very vague, and big words, but the paper I wanted to write about it together with a friend of mine never materialized:(

uff… more infos on the treaties, you would get by looking them up:

http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b3ccpr.htm

There are also a lot of cases by the European Court of Human Rights, though of course not applicable to India, but if you are interested in the legal reasoning, just search for ECHR and go on their website.